MAY 28, 2015 — Caroline, a 24-year-old South African, and I have been together on the sidewalk in front of the train station in Bayonne, France, for three hours, waiting for a bus to take us to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, France, a traditional starting point for the 870-kilometer (540-mile) historic pilgrimage across Spain called the Camino de Santiago. We’re watching as droves of other pilgrims (as Camino walkers are called) from all over the world arrive at the station, hoping to be transformed and inspired by a trek considered by many to be as much of an inward journey as a physical one.

Admittedly, Caroline and I, not having (yet?) reached the Zen state promised by our upcoming Camino, are judging the people who pass by us a little bit. Maybe a lot.

“Is that woman seriously going to hike 500 miles in jeans?” I wonder. “I helped her with her backpack on the train, and it weighed almost half as much as her.”

“Did you see that guy had made his own walking stick?!” Caroline asks.

“Wow,” I respond. “That’s a real man. Mine were made in a factory.”

To be honest, even Caroline looks like she’s likely to die during her first day on the Camino. She’s carrying a big cardboard box filled with who-knows-what, her backpack is overstuffed, and she’s wearing boots better suited for a night out at a posh club in Paris than a 500-mile hike. Many people walk the Camino with a specific goal in mind, hoping to process a recent misfortune or make a big life decision, but, as Caroline and I talk, it becomes clear that the two of us haven’t given much advance thought to why we want to walk the Camino.

Pilgrims eat breakfast at an albergue in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, France before beginning their walk on the Camino de Santiago.

“I’ve done hikes all over the world, and I’ve wanted to do this one for a long time,” I tell her. “I managed by some miracle to carve out enough free time, so here I am!”

“I just decided to do this four days ago because I realized I have nothing better do to with my life right now than travel the Camino,” Caroline explains. “I was traveling around Europe with a friend, but she had no interest in doing this.”

While we’re talking, another young woman sits down next to us on the sidewalk. She tells us that she’s a 24-year-old medical student from Denmark named Amalie, and I experience déjà vu. I’m reminded of my first day of college and its rare storm of social perfection: a large group of people coming together with similar aspirations, uniquely open to empathizing with strangers and meeting new friends.

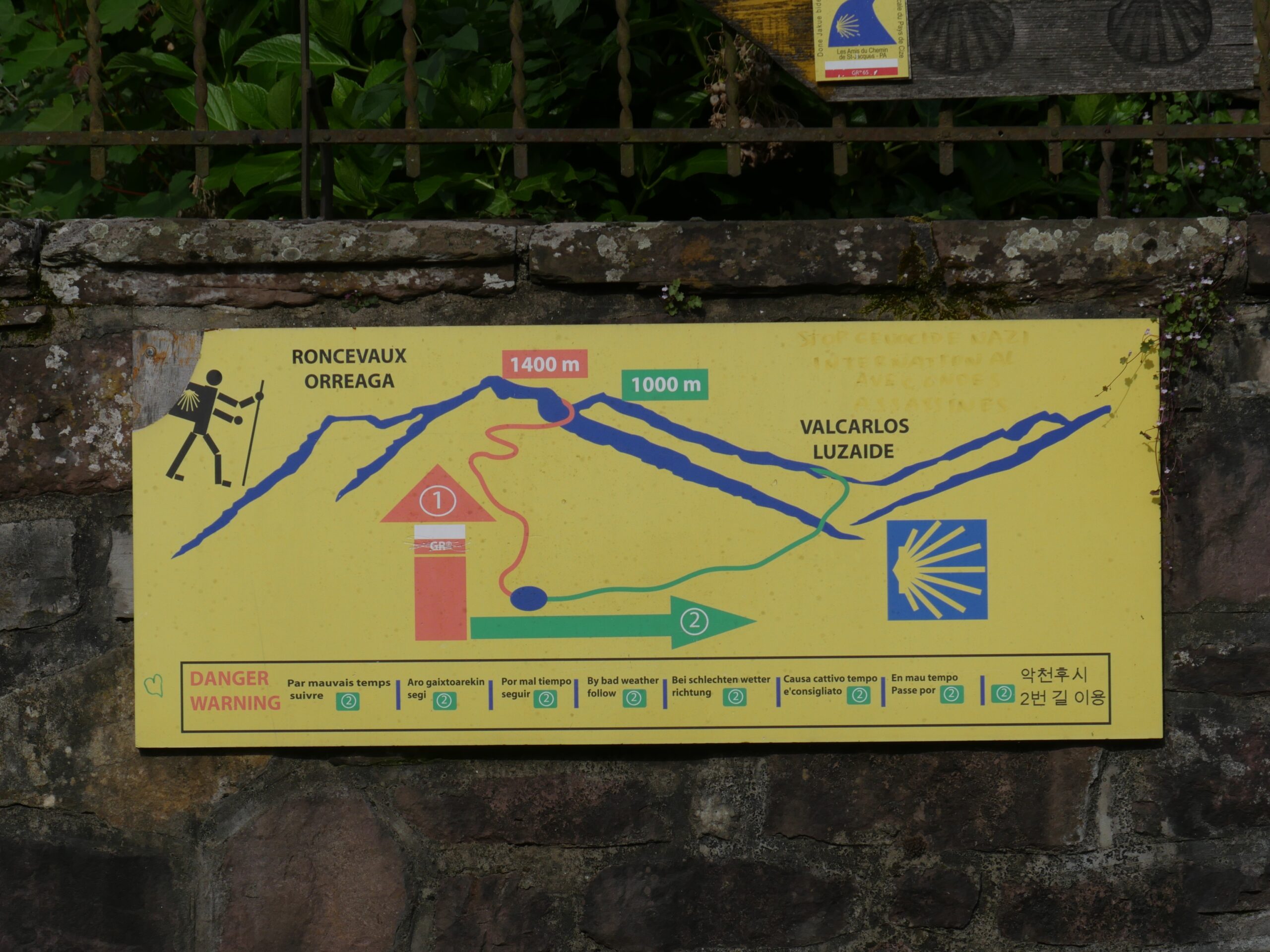

A sign warns Camino de Santiago pilgrims of the dangers of attempting the difficult Napoleon Route leading through the French Pyrenees.

“Did you see that guy over there?” Amalie asks, pointing to homemade-walking-stick guy. “He told me that he just returned after walking the Camino in both directions.”

“1,000 miles?!” I say. “That’s crazy. Why would anyone want to do that?” But I realize that my logic isn’t totally sound, considering that walking the 540-mile Camino twice is only marginally crazier than my plan to walk it once.

After a short bus ride, Caroline, Amalie, and I arrive in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port with about 100 other pilgrims, and we jump into a long line outside an office issuing credenciales, a special passport which allows hikers to use the Camino’s network of hostels (known as albergues). Afterward, we wander around looking for empty beds, but we’ve arrived in town late because our bus was overbooked by 20 people (no, I have no idea how this could happen either) and we had to wait for a second one. Eventually, Caroline and Amalie find beds at hostels down the street, but I’m left stranded for awhile until I eventually discover a single bed remaining at a pleasant albergue in the midst of serving a family-style dinner. The owner seats me next to Amanda, a 45-year-old South African — whom I recognize from earlier in the day as the jeans-wearing woman with the ridiculously heavy backpack — and Katie, a 27-year-old American ex-lawyer from Virginia.

Sheep watch as pilgrims hike the Camino de Santiago through the French Pyrenees.

“I hated my job, so I quit,” Katie tells me as we wolf down bean stew together. “I’m going to school later this summer to change careers and move into publishing, so this was a perfect time for me to do the Camino.”

In the morning, with my backpack weight hovering just above 9 kilos (20 pounds) — I’m embarrassed that I didn’t have the discipline to leave my electronics and board games behind — I climb a hill to visit the town’s citadel and then begin the first stage of the Camino called the Napoleon Route, a notoriously-punishing 25-kilometer (15-mile) day with an 1,250-meter (4,100-foot) elevation gain over the Pyrenees mountains. I hike through rugged, tree-covered mountains with lush, green fields dotted with chocolate-colored horses and strangely orderly lines of cream-colored sheep. Near the hike’s high-point, the wind becomes so strong that some smaller, older pilgrims don’t have the strength to push forward against the ferocious winds, and I see a small, overwrought woman screaming at her husband.

Camino de Santiago walkers make their way through the French Pyrenees on the infamous Napoleon Route.

“You need to fucking wait for me!” she yells. “You don’t understand how fucking strong the winds are! Stop going ahead of me!”

It’s clear that the the Camino’s alleged transformative powers don’t necessarily kick in on the first day, I think. They’ll never make it 500 miles together. I stop to eat a sandwich that I packed for myself and, then, falling into a post-lunch food coma, I promptly fall asleep in the middle of a grassy field near a flock a sheep. An hour later, I wake up, confused that I’m not in my bed in Los Angeles. Oh, it’s the French Pyrenees, I realize. I guess I need to keep hiking.

When I finally reach Roncesvalles (the next major stop on the Camino), I walk past rows of pilgrims who look like people who thought that had signed up for beginners’ yoga class but were unexpectedly sent instead through Navy SEAL training. My mid-day nap in the Pyrenees put me hours behind most of the other pilgrims, and all of the albergue beds have been taken, but the hospitalero gives me space on a bunk bed in a bathroom-sized modular trailer with seven women. After a communication-challenge dinner with a Japanese guy who speaks neither English nor Spanish fluently, I wander through the common area of the albergue and find Katie, who now looks more like someone who accidentally fell asleep in a tanning bed for a week than someone who spent a single day hiking through the Pyrenees.

Stop sign graffiti in Spain encourages pilgrims walking the Camino de Santiago.

“Uh, maybe try sunscreen next time?” I say to her. She smiles and introduces me to Grant and Ashley — a young married couple from Australia’s Norfolk Island — and Ashley’s mother, Mosta.

“You can remember it because it’s like ‘monster’,” Grant says. Hiking 500 miles with your wife and mother-in law sounds like a dangerous project, I think. Katie tells me that the three Australians are deeply religious and that they’re hoping to move closer to God on the Camino.

The next morning, feeling unclear about why I ever thought a 500-mile hike across Spain would be a good idea and why anyone would think that God would endorse the torture of daily 15-mile walks that start before sunrise, I begin walking at 6:00 AM to coincide with Katie’s group’s schedule. The four of us walk along forest paths lined with oak trees and through quiet Spanish towns. As we walk, Katie tells me that she spent time working for an NGO in Tanzania, and we find ourselves discussing some of the best books we’ve read about Africa, including King Leopold’s Ghost, a harrowing depiction of Belgium’s colonization of the Congo. I realized that I’m already absorbed by the diversity and depth of the people on the Camino.

People fill the streets of Pamplona, Spain on a Saturday evening.

Around noon, we arrive in the small town of Zubiri. I’m relaxing at a cafe, eating a huge meal, when Amalie (from the Bayonne train station) appears with a Hungarian girl named Kate in tow.

“We’re heading to the next town, but I thought we should stop to have some sangria with you first,” Amalie announces as the two sit down at my table. The sangria flows fast, and we quickly fall again into a discussion of why we’re doing the Camino.

“I need to figure out what God wants me to do with my life,” Kate explains.

“After my radiology internship ended, I had a lot extra time for watching Netflix, and I saw [the film starring Martin Sheen about the Camino de Santiago] ‘The Way,’” Amalie says.

“So, basically, you’re doing the Camino because of Netflix,” I quip.

“I supposed you could say that, though I also need some time away to decide on my medical specialty,” she says.

The next morning, Katie, Grant, Ashley, Mosta, and I hike toward Pamplona, and we spend much of the time ranking our favorite animated Disney movies. I argue for The Little Mermaid and Wall-E, Katie likes Lilo and Stitch and Mulan, and Grant thinks the whole conversation is ridiculous. In the small hamlet of Zuriáin, an 18-year-old German kid named Kai catches my eye because he’s carrying two heavy backpacks, one clipped to the other on his back, pulling hard on his shoulders.

Bunk beds fill the Jesús y María albergue in Pamplona, Spain.

“You’ve got to get rid of one those, man,” I tell him. “Your shoulders are going to fall off.” He tells me that he’s doing the Camino as part of a gap year before starting a technical college. We walk together toward Pamplona, as rolling wheat fields turn into small towns which turn into suburbs which turn into the sidewalks, sewer grates, and lampposts of a major city. I’m hypnotized by the unique experience of this walk — an urban hike where travelers can watch countryside turn slowly into a city before their eyes. Kai and I catch up to Katie, Grant, Ashley, and Mosta in a city park, where we feast on baguettes and serrano ham that Grant has been carrying in his backpack. Afterward, the six of us check into Jesús y María, a huge municipal Pamplona albergue, built in an old church with 60-foot-high ceilings and over 100 bunk beds. Wandering among the sea of beds, I find Amelie again, who has befriended a 17-year-old British kid named Harry (not Potter) and a 64-year-old Canadian eccentric, with an affinity for making balloon animals, named Brock.

Pitchers of sangria sit on a table at Cafe Iruña in Pamplona, Spain.

With her help, I round up nearly everyone I’ve met on the Camino so far: American, sunburned Katie; Danish, Netflix-obsessed Amelie; German, two-backpack-wearing Kai; Australian newlyweds Grant & Ashley with mother-in-law Mosta; British Harry (not Potter); and Canadian balloon-animaler Brock. We walk to Pamplona’s large city square and collapse into chairs at a table at Cafe Iruña. We’ve hiked nearly 70 kilometers (43 miles) so far. Our bodies aren’t used to walking so much, our social batteries are drained because we’ve met so many new people, and we can’t manage to stuff enough food in us to fuel the madness. But, pitchers of Pamplona’s deep-red, sweet, citrusy sangria never seem to stop coming. We laugh and learn and share, and it feels like it’s the first day at the world’s most eclectic college.

I look around at everyone, and I feel a strong ache of regret. At this moment, I can’t think of a single good reason why it took me so long to end up here. There’s nothing that could have been more important than undertaking an epic walk across Spain with this motley crew of beautiful, compassionate strangers.

Blisterland

Learning from blisters and the fleeting nature of relationships on the Camino de Santiago.

JUNE 10, 2015 — When I step out of the huge church that I slept in overnight in Pamplona and onto the uneven, cobblestone street, it feels like there’s a razor blade stuck in each of my shoes. Though I can barely walk without screaming due to the pain, I hobble down the block so slowly that it takes me almost 10 minutes just to reach the corner. Then, with horror, I realize that I’ve walked in the wrong direction to rejoin the Camino. I turn around and spend another 10 minutes hobbling to the corner at the block’s opposite end. Anyone watching me from afar would think that I’m a 98 year old man just hours away from needing a permanent wheelchair — or being visited by the grim reaper.

An art installation depicting pilgrims walking the Camino de Santiago sits on a ridge above Zariquiegui, Spain.

Over the past three days, I’ve taken about 93,000 steps, many of which have been on hard pavement, and a big blister has formed on the bottom of each of my feet. Though I already broke in my boots, with over 130 miles in Nepal and Arizona before the Camino, I’m starting to realize that they may be the wrong footwear for this trip. The majority of the Camino route is on paved surfaces, and the unforgiving asphalt is hard on feet and knees, especially with my stiff boots. Nearly everyone I’ve met walking the Camino has developed feet blisters by now — in a twisted, nightly ritual, pilgrims often show off their wounds to each other — but my blisters are not the typical, easily-treatable friction blisters caused by a shoe rubbing against skin that most have shown me. Instead, my super-blisters-of-death are composed of layers of damaged tissue and a well of fluid sloshing around under the surface of my skin, and I have no idea how to fix them.

Street art reminds hikers to have a “Buen Camino.”

While limping through Pamplona, I spot the Santa María de Real Cathedral and, since it’s Sunday, I slowly drag myself into the mass to give myself a rest. I stay for about 15 minutes, listening to the priest speak in Spanish, and then I return to the street, where my feet hurt so much that I can feel tears coming to my eyes. Even the Kas lemon soda and cream donut that I eat at a small cafe doesn’t manage to raise my spirits.

Very, very slowly, I start to leave Pamplona behind, but my (lack of) speed is almost comical in its sluggishness. Sunburned Katie, newlyweds Grant & Ashley, two-backpack-wearing Kai, and Netflix-obsessed Amalie are all many kilometers ahead of me by now. I pass through grassy, Taconera Park, split by a sparkling, cool river, and then past another park surrounding the large, star-shaped, 16-century Pamplona Citadel, taking frequent breaks. I run into a smart, 21-year-old Yale student from Hong Kong named Stephanie, with an effervescent personality. But, she’s walking the Camino at an accelerated pace due to a limited schedule, and I can’t keep up with her due to my blisters. She quickly disappears over the horizon.

Pamplona, the largest city on the Camino de Santiago, is surrounded by fields of wheat.

I begin a steep climb up toward a forest-green mountain ridge lined with 20 brilliant white, spinning windmills. Tens of other Camino walkers, some double my age, keeping passing me. “Buen Camino!” they say over and over, too enthusiastically. It’s the standard pilgrim goodbye, which translates roughly to “Have a good Camino!” or “May your Way be good!” but hearing it repeated, when I can barely walk, only makes me more frustrated. “It’s really a mal [bad] Camino,” I want to yell at them.

Signs point to the way to Santiago and other cities near windmills above Zariquiegui, Spain.

The pain in my feet is so excruciating that I consider collapsing on the side of the trail in one of the grassy fields and sleeping there for a week. I slowly realize that I have no chance of making it to Puente la Reina today, a town which is still over 16 kilometers (10 miles) away even though I’ve already been walking for hours. Even worse, it dawns on me that I’m never going to see my Camino friends — Katie, Grant, Ashley, Kai, or Amalie — ever again. Though I knew them for only three days, the Camino has a way of intensifying and accelerating relationships by thrusting people outside their comfort zones, pushing them beyond their limits, and forcing them to spend sometimes 10 hours every day with each other. On top of that, because the kind of people doing the Camino tend to be especially open and introspective due to the special history of the trip, spending a day with someone on the Camino can feel spending three months with a new friend in the “real world.” But, I’m starting to learn that people appear and disappear from your Camino, and, often, you just have to let them leave you behind.

Rolling barley fields surround the Camino de Santiago in Spain.

Unable to take even one more step, I wander into the albergue in Zariquiegui, a small town tucked just below the string of windmills on the top of the ridge. I must look like a person walking with razor blades in his shoes, because the hospitalero takes one look at me and says in Spanish, “There are beds upstairs. You can pay later.” Feeling horrible pain in each step, I trudge slowly up the stairs. To my surprise, I discover a room with twelve bunk beds, empty except for my friend Amalie, who is sleeping on a bunk in the corner. Later, she tells me that she developed a fever during the night in Pamplona and, like me, could only make it to Zariquiegui before feeling too weak to continue walking.

A Camino pilgrim looks out at fields of barley while walking the Camino de Santiago.

Over dinner, she tells me that one of the reasons that she’s doing the Camino is that she needs time away to decide on her medical specialty for medical school. She says that she decided to become a doctor as a young girl after seeing her mother, who is also a doctor, rush to help a woman who fell ill and collapsed in a park. Before going to sleep, Amalie helps me thread my blisters, a technique which entails running a threaded needle through the blister in an attempt to drain the fluid.

The next day, even after a night sleeping in a room filled with ear drum-popping snoring, my blisters, though still very painful, have improved. Amalie and I begin hiking together to the ridge lined with windmills above the town. At the top, we encounter a Camino-themed art-installation: dramatic, metal silhouettes of pilgrims walking the Camino, backed by expansive views of the lush valley, sweeping back toward the shiny white and red-roofed buildings of Pamplona, the biggest city on the Camino. We continue down the mountain, walking through rolling hills, blanketed with thousands of stalks of light-green barley, rice, rye, and wheat, shivering in tandem from the pulsating breeze. While we walk, Amalie, who tells me that her mom grew up on a farm, teaches me how to identify the different crops. While I’m hypnotized by the stalks moving in seemingly choreographed waves, with shimmering, swirling shapes of light and dark shadow, Amalie plays a song on her phone.

The El Crucifijo Church in Puente la Reina, Spain has a large bell tower.

You’ll remember me when the west wind moves Among the fields of barley You can tell the sun in his jealous sky, When we walked in fields of gold.

Performed by Eva Cassidy and written by Sting, it’s a song which some might perceive as cloying, and I usually avoid music while hiking because I prefer the world’s natural sounds. But, as Amalie and I literally walk through fields of barley, her song feels appropriate and poignant — a perfect choice. This is the thing I learn about Amalie today: her endearing naiveté hides sophistication.

A famous, six-arched bridge allows hikers to cross the river in Puente La Reina, Spain.

Eventually, we arrive at an intimate albergue with a quaint elevated patio in the small town of Cirauqui. When the woman at the desk sees me wincing with each step due to my blisters, she suggests putting women’s sanitary pads in my shoes to reduce the moisture in my boots. At first, I think she’s joking. She’s not.

In the evening, while eating excellent spaghetti and meatballs, the best dinner I’ve had so far in Spain, Amalie and I talk to Garðar, a 60-year-old Icelandic man and who tells us that he has walked the Camino four times: in 2007 and every year since 2012. This year, he began far north of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in France (my starting point) and plans to hike 1,800 kilometers (1,100 miles).

The town of Cirauqui, Spain sits among grape vineyards.

“Why do you keep doing the Camino over and over?” I ask him. “Isn’t once enough?”

“Every time I do it, I become a bit more mature,” he says. “I become a better person and get a little closer to my true self.”

He’s sitting with a Minn, a Belgian woman whom he met while walking the Camino in 2007. She says that both she and Garðar were in relationships with other people when they walked in 2007. But, a few months ago, she sent him a Facebook message.

“I never thought I could do the Camino again, but, now, I’m in a divorce, so, suddenly, I could,” she says, smiling. “Back then, I fell in love. And, now, we’re walking together again.”

But, the next day, I can’t imagine finishing the Camino even once, let alone four times. By the time Amalie and I reach Estella, we’ve walked 115 kilometers (71 miles), and my feet hurt more than they ever have before. I realize that there’s absolutely no way I’ll be able to walk the remaining 755 kilometers (470 miles) across Spain to the ocean with my feet in their current state. My feet look ravaged: each has an open wound on the bottom and many additional blisters have developed. For the first time ever, I realize that finishing the Camino de Santiago may not be within my ability.

The Maralotx albergue in Cirauqui, Spain has a quaint, elevated patio.

I tell Amalie that I can’t keep walking and must see a doctor immediately. We find a building with a “Centro de Salud [Health Center]” sign, and I see a notice in Spanish, next to a computer, that says that visitors must have appointments. I start filling out a strangely detailed questionnaire on the computer in Spanish, which asks a lot of surprisingly personal questions just to schedule a doctor’s appointment. At the end, the computer spits out an appointment time in one hour, so Amalie and I decide to get ice cream and return. On the way out of the office, however, a man tells us me in Spanish that, if I’m looking for the hospital, it’s in the adjacent building. We suddenly realize that we’ve just spent a half hour applying for Spanish social security. I can’t wait for the checks to start rolling in.

Storm clouds hover over the Camino de Santiago on the way to Puente La Reina, Spain.

At the hospital, the Spanish-speaking doctor looks at my blisters. He tells me that they’re very bad (no surprise) and tries to use the least patronizing voice he can muster to suggest that, maybe, I should stop walking for a few days until my feet heal. He then sends me to two nurses, who, both shocked by the horrific state of my feet, work in tandem as fast as possible to clean and bandage my wounds. The nurses can’t speak English, but everything is clear when one of them types some advice for me into Google Translate: “Stop walking and don’t touch the feet.”

Spanish nurses bandage blisters on my feet in a hospital in Estella, Spain.

“What did they say?” Amalie asks when I meet her outside the hospital.

“They said to stop walking,” I say. We don’t talk any more about it.

We both know that relationships on the Camino are maddeningly fleeting: feet get injured, illnesses arise, and schedules don’t coincide. You simply enjoy people’s company as much as you can when you’re with them and then learn to let them go when they’re gone. It’s as true on the Camino as in life: I tried to do the same thing when my dad passed away four years ago.

In the evening, Amalie and I have dinner together in the town square. I tell her that I love Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. She tells me that she loves a Danish romantic comedy called Den Eneste Ene. Some tiny dogs wander by in front of a gazebo. I tell her about a band that played in the gazebo during the “Ice Cream Social” that we had in my hometown in Ohio when I was a kid. She tells me that tiny dogs freak her out.

Bandages wrap my foot after considerable care from two Spanish nurses in Estella, Spain.

In the morning, Amalie and I check out of our albergue. She’s heading toward Los Arcos, the next major town on the Camino, and I’m going to check into a hotel here to give my feet time to heal. In a day or two, I’ll be so far behind her Camino that I won’t have any chance of catching up.

“Well, I guess it’s buen Camino,” Amalie says.

“But it’s too sad,” I say. We both know that we’ll never see each other again. We hug for an extended moment. Then, she turns away. I watch her as she crosses a small blue bridge, walks down a street lined with cafes and small stores, and continues on toward the rolling red hills and forested hilltops separating Estella from Los Arcos, until she’s almost out of sight.

It’s hard to let her go. “Buen camino!” I yell as she disappears. But it’s too late. I’ve been left behind, unable to walk, on the Camino de Santiago.

Bending time

How the sheer length of the Camino de Santiago changes the way people live.

JULY 10, 2015 — I’m sitting alone on the edge of an expanse of barley near Viana, Spain, eating gummy bears and gulping down water from my CamelBak. It’s almost silent, except for the sound of barley stalks swaying in the strong wind, like a broom sweeping slowly across a tile floor, and the intermittent popping of drizzle, dampening my backpack. Surfacing from the quiet, I hear the tap-tap, tap-tap of hiking sticks in the distance, quickly getting louder. A 26-year-old woman with a purple backpack and drenched, blond hair crinkles her nose as she approaches. “Horrible weather,” she says to me with a British accent as she catapults by, disappearing behind a hill without another word, her tap-tap, tap-tap swiftly diminishing.

Hikers walk past a wooden cross above Atapuerca, Spain.

After being bedridden in Estella for a day and a half to give my soul-crushing feet blisters time to heal, I’ve been limping along for two days since, completely by myself, leaving later in the morning than most hikers and unable to keep up with anyone on the trail anyway due to the pain. The solitude has given me time to let the distinct feeling of walking the Camino consume me. On most hiking trips I’ve done, when I’ve felt uncomfortable or just plain miserable, I’ve been able to take solace in the fact that the end to my inquietude is only days away. But, the Camino is different. Though I’ve already been walking for nine days, so much time (over a month) remains before I’ll (hopefully) reach the Spanish coast that it’s impossible for me to look ahead to see or imagine the finale. The Camino’s overwhelming length forces me to focus on every day moments — like the quiet sounds of a barley field — because the trip’s end is nowhere in sight. Sitting in this verdant ocean of grain, being pelted by wind and rain, time seems to stretch to infinity.

An ocean of barley surrounds the Camino de Santiago near Viana, Spain.

Eventually, I decide to get up and start hobbling down the trail, but I realize that it’s time that I do everything I possibly can to fix my feet, in a last-ditch effort to begin enjoying the Camino again and increase my chances of making it to the end. So, when I arrive in the large city of Logroño, I head directly to a sports store called Planeta Agua that I’ve heard other hikers mention. I explain in a desperate tone to the Spanish store owner that I suspect that my stiff boots are destroying my feet, my Camino, and my life. He appears sympathetic but unfazed, and it occurs to me that this Saint of Comfortable Shoes deals with tens of desperate Camino walkers in tears every day, hoping for him to save their Caminos, and maybe, their souls. After all, the Catholic church forgives all of the sins of those who complete at least 100 kilometers of the Camino, and this guy may very well be my key to absolution.

People gather in a plaza in Logroño, Spain.

The Saint of Comfortable Shoes disappears into his storeroom and returns with a pair of green Salomon trail runners. I’m worried that the shoes’ soles will feel too soft and squishy when paired with a heavy backpack — the primary reason that I didn’t start the Camino wearing trail runners — but, at this point, I’m desperate. I slip the shoes onto my feet.

Hands down, it’s the most religious experience that I’ve had on the Camino so far. I feel like I’m floating through heaven as I stroll around the store, and though the Saint of Comfortable Shoes seems mildly pleased by my endless barrage of gracias, gracias, I can see in his eyes that this is the 38th time today that this exact thing has happened. When I pull out my credit card to pay, he quietly mentions that, the day before, he met my Danish friend Amalie and sold her a new backpack. That means she’s only one day ahead of me, I realize. I have no idea how he suspects that I know her, but I can only assume that the Saint of Comfortable Shoes has access to a knowledge database of which we mere mortals can only dream. He hands me a small gourd — a miniature representation of the kind medieval pilgrims used to carry drinking water during their pilgrimages — and I notice that it’s stamped with the phrase: “Buen Camino, peregrino [Have a good Way, pilgrim].”

The owner of Planeta Agua stands outside the store in Logroño, Spain.

I thank him, and, as I bound out of the store with newfound strength, I hear him yell from behind me, “Buen Camino!”

For much of the next day, I feel like the Saint of Comfortable Shoes has given me entirely new feet. I can’t believe how much better I feel. Still, my Satanic blisters aren’t totally healed yet, and I find that I’ve run out of energy a handful of kilometers before reaching Nájera, my next overnight stop. I’m about to sit down to take a long break when I see the British “Horrible Weather” girl approaching again. This time, with the drizzle long gone, she stops to chat and tells me that her name is Hannah. She’s walking with Arnaud, a 32-year-old man from Mauritius, with salt-and-pepper hair and a wry smile. The two of them have clearly been in love for years, and they’re walking the Camino while holding hands, stealing kisses, and basically looking like the cutest couple that has ever graced the Earth. Hannah tells me that after her graduation from Oxford, she quit her publishing job to rethink her career, while Arnaud jokes that his most recent job “quit him.” I’m shocked when Arnaud tells me that he and Hannah actually haven’t been dating for years, but met only 5 weeks before, when they started walking the Chemin du Puy, an extended section of the Camino starting in Le Puy in central France. All my Camino bragging rights dissolve when I realize that, though I’ve walked 195 kilometers (121 miles) so far, these two have done almost five times that — 931 kilometers (578 miles) — just to get where we are.

I purchased new Salomon trail runners to replace my stiff hiking boots in Logroño, Spain.

And, yet, to Hannah and Arnaud, the distance they’ve walked seems unimportant. They’ve traveled so far that, somehow, it doesn’t matter how far they’ve already gone or how far we’re going to go in the future.

A gourd, representing those that medieval pilgrims used to carry water, sits strapped to my backpack after I received it as a gift from the owner of the sports store Planeta Agua in Logroño, Spain.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do once I get to Santiago; I’ll probably just keep walking — maybe to Portugal or on one of the mountain routes,” Arnaud tells me. We pass a man in his seventies wearing a black cloak, and, unexpectedly, Hannah disappears behind us for a bit. “The end is so far away, I’m just not thinking about it much,” Arnaud adds. “Time is different here. I’m just living.” I realize that he’s right: I don’t know what day of the week or month it is. I can’t remember what my life was like before I decided to simply walk, every day, until I can’t walk anymore. The Camino bends time, somehow erasing the past, obscuring the future, and intensifying relationships, making two acquaintances who have known each other for only a handful of weeks seem like a couple about to celebrate their 40th wedding anniversary. It’s a humbling alternate universe.

Hannah and Arnaud walk hand-in-hand on the way to Nájera, Spain on the Camino de Santiago.

Hannah reappears from behind us.

“He told me that his wife, Anna, died a few months ago,” she says, referring to the man in the cloak that we passed. “He decided to walk the Camino to take time to deal with his grief.” I’m struck by the gravity of the man’s story, but I’m even more touched by Hannah’s natural inclination to break away from us, two Camino walkers near her own age, to spend some time with a man over 40 years older than her. This is the thing I learn about Hannah today: her lithe exterior and pedigreed education only distract from her truly empathetic soul. And, as the three of us continue together toward Nájera, I watch Arnaud playfully whisper jokes into Hannah’s ear, sprint up big hills next to the trail, and explore mysterious medieval grain silos. I can see that he has an energetic spirit and boundless natural curiosity, and it becomes obvious why he and Hannah have been glued together for over 900 kilometers. Together, their enthusiasm is infectious, and when the three of us end up in a dorm room together in Nájera and begin to fall asleep, I can feel my own energy for the Camino renewing.

Groomsman and a decorated car sit outside the Iglesia de La Asunción in Navarrete, Spain in preparation for a wedding.

The next morning, Hannah and Arnaud leave in the morning well before me, but I’m surprised to discover that I feel okay about saying goodbye to them, at least for now. Just live, I think. There’s so much time here that you never know what can happen.

A man fishes in a lake near Logroño, Spain.

An hour later, after walking five kilometers out of Nájera, I walk into a cafe in Azofra and notice a brand new backpack sitting on the floor. Strangely, there’s a small water gourd hanging from it, identical to the one that the Saint of Comfortable Shoes gave me before I left his store in Logroño. I look up. Sitting next to the backpack is Amalie, the Danish, Netflix-obsessed medical student who, a week ago when my blisters were at their peak, I was sure I would never see again.

Pile of burdens

Trying to come to terms with why I’m walking the Camino de Santiago.

JULY 23, 2015 — “I’m at a crossroads in my life,” says Bae, a young South Korean woman with long black hair and a shy smile. “I’m walking the Camino to decide what I’m going to do with the rest of it.”

Danish Amalie and I are sitting together, with 30 other Camino pilgrims and four nuns, in the reception room of the Santa María albergue in Carrión de los Condes, Spain. Just 10 days ago, Amalie had pulled almost two days ahead of me due to my blisters, but we reunited by luck in Azofra, where she revealed that tendonitis had slowed her progress down for a couple days, allowing me to catch up. Together, we then powered through eight days of walking, bringing our Camino total to 370 kilometers (230 miles). Now, we’re sitting next to Uta and Laura, two young Estonian sisters with whom we shared dinner two nights before in Hontanas, one of the Camino’s most inspiring towns, tucked deep in a valley in the Meseta, Spain’s central high plateau. The four of us cooked and shared a pasta dinner together, because we were all dying for a Camino meal that didn’t involve some kind of pig product. The Spanish seem to try to infuse every meal with ham and bacon, which sounds great, and it was, until the day I found myself stuffing my fiftieth Serrano ham sandwich into my gut.

A Camino pilgrim holds a stone representing life burdens at Cruz Ferro, near the high point of the Camino de Santiago.

Amalie and I were looking forward to reaching Carrión de los Condes, not only because of its rich history (Charlemagne used it as a base in his fight against the Moors), but also because Amalie saw a Youtube video of a gaggle of nuns entertaining Camino walkers with folk songs there during her disturbingly in-depth pre-Camino research. (So far, we have seen nothing on the Camino that she hasn’t already seen in advance on Youtube.) Knowing that seeing these singing nuns would be the closest we’d be able to get to a reenacting the venerable Sound of Music during our trek, we made sure to arrive early to get a spot for the performance.

Four nuns sing in the entrance hall of the albergue in Carrión de los Condes, Spain.

But, before singing, the nuns have asked everyone in the room — hikers ranging from 16 to 75 years old, hailing from North America, Europe, and places as far away as Chile, Japan, Australia, and Zimbabwe — to share their name, country of origin, and why they’re walking the Camino de Santiago.

“Walking the Camino has always been my biggest life dream as long as I can remember,” says a 50-year-old American woman with white hair, a red sweatshirt, and red-rimmed reading glasses. “So, the day after I retired, I flew here.” I’m amazed when at least a quarter of the people in the room (many of them Catholics) echo her life-dream sentiment. Estonian Uta reveals to the group that her boyfriend recently broke up with her, so she’s walking the Camino for as much time as it will take her to get over it. Jerzy and Sylwia, a young married couple from Poland, say that they walked the Camino for their honeymoon five years ago — and recently, they decided that it was time for them to do it again. “We are doing the Camino a second time because we forgot how the first time was painful,” Jerzy adds, half-joking. “We don’t know why we are here, but we know that we need to be here.”

A priest performs a pilgrim blessing in the Church of Santa María in Carrión de los Condes, Spain.

Later, Catherine, a 50-year-old woman from Orange County, California, with whom I spent two days on the way to Belorado, reveals that she and her husband divorced a little over a year ago and she, too, is trying to figure out her next life steps. Erin, a 27-year-old woman from Colorado, tells me a nearly identical story about a divorce that happened only two months before. And Father Dave, a pastor from a church at Colorado State University, explains that he’s walking to lead a group of college students on the Camino. He then adds, “For me, I haven’t, internally, figured it out. I still don’t know why the Lord wants me to do it.”

A shepherd guides sheep down a road near Boadilla del Camino, Spain.

So, by the time my turn comes, I’m worried that my standard explanation — that the Camino was next on my long list of travel adventures that I’d like to finish before dying — seems a bit shallow. But, before I can think more about it, the nuns start into a rendition of Amazing Grace and then transition to a potluck of other folk songs from around the world, suggested and sometimes sung by the far-flung pilgrims in the room. Then, they usher us into the adjacent church for a special pilgrim’s mass and blessing.

“We’ve made each of you one of these paper stars,” explains one of the nuns, holding up a cookie-sized star made out of copy paper, colored with a rainbow of crayons. “Keeping these in your pocket will help you remember that God is always with you to guide your way.” We all form a line, and when I reach the front, one of the nuns hands me one of the stars as the priest traces the shape of a cross on my forehead. Though I’m not a religious person, the Camino can be a spiritual journey for anyone, and the moment has symbolic weight for everyone, me included. Still, when I see Bae, Catherine, and Erin crying as the priest touches their foreheads, I feel like an impostor — and I don’t know exactly why.

A man leads a donkey down the Camino de Santiago near Boadilla del Camino, Spain.

Three days later, Amalie and I are walking on the isolated, 18-kilometer (11-mile) section of rocky Roman road leading to Mansilla de Las Mulas, the last town in the Spanish desert before arriving in the comparative metropolis of León. Though proving cause and effect is impossible, my feet have been in perfect condition for the first time on the Camino, ever since I attended the pilgrim blessing in Carrión.

“I feel like I’ve been lying to people for the whole Camino,” I say.

“Really? What do you mean?” Amalie asks.

“Well, so many people have told me about complex reasons for why they’re doing the Camino: strong religious faith, parents dying, divorce, or being fired from an important job,” I say. “But, I always say that, for me, the Camino is just another adventure.”

Shadows of two pilgrims appear on a historic Roman road near Mansilla de Las Mulas, Spain.

“Well, of course that’s not true,” Amalie points out. “Or, at least, it’s not the only thing that’s true. Some people are just more open to sharing personal details with strangers than others.”

“Exactly. To be honest, I probably wouldn’t be here if I were married with kids, crazy rich, or wrapped up in a perfect career,” I say. “Back home, I’ve missed a lot of opportunities over the last ten years, and now it feels like it’s too late to fix my mistakes. It’s frustrating. But, I’m not sure how the Camino can help that.”

I step off the road for a moment so I can find a private place to pee. Immediately, I stumble into a deep hole and sprain my ankle. “Fuck!” I yell. “I am so stupid!”

“Are you okay?” Amalie yells. I limp sheepishly out of the bushes, barely able to walk. “It’s fine. It’s fine. I think it’s probably fine. It’s fine,” I say, trying to convince myself and her.

Flags wave in the wind outside a hotel room in León, Spain.

“Well, if you can’t walk on it, we can try to call a taxi,” Amalie suggests.

“Not in a million years,” I say. Since the start of the Camino, I’ve had a strict rule that I won’t allow myself to use any kind of vehicle until reaching the Atlantic Ocean, and now that I’ve walked every single one of the 447 kilometers (277 miles) to get to this spot on a Roman road, there’s no way I’m going to admit defeat now. So, with ankle pain increasing, I manage to walk the remaining 13 kilometers (8 miles) to Mansilla de Las Mulas. There, I spend the evening sitting at a plastic picnic table in the courtyard of our albergue, icing my ankle, which has swollen to grapefruit-size. While I’m holding the ice, a 55-year-old man with a Georgia accent and salt-and-pepper beard spots the Appalachian Trail sticker on my laptop (from my brother’s AT bachelor party) and asks if I have ever hiked the entire Appalachian Trail. When I tell him that it’s only a dream of mine, he introduces himself as “Hammer” and his two friends as “The Professor” and “Sensei.”

A statue stands in the plaza in front of the León Cathedral.

“They’re our Applachian Trail names,” Hammer says. “Twenty years ago, we all met each other while we were through-hiking the entire Trail. Now, we’ve reunited to do the Camino together.”

“It rained for the first 38 days of the Applachian Trail, but, still, it was the best thing I’ve ever done in my life,” the Professor tells me. “You have to do it.” He tells me that, when he met his wife afterward, she wanted to do the AT too, so he did the whole 2,200-mile (3,500-kilometer) hike again. “At the end, when I got into a car for the first time, it was so weird,” he continues at length, fulfilling the promise of his eponym. “I had only been walking at four miles per hour for six months. Everything moved too fast. It was scary.”

A striking Gothic bridge is the defining feature of Hospital de Órbigo, Spain.

An image flashes through my mind. For a second, I can see myself getting into a bus in Finisterre, on the Spanish coast, to return to the airport, and I realize that my arrival in Santiago is only 14 days away. For the first time, I can glimpse the end of my Camino, and the idea of it ending scares me. What if I make it to the end without figuring out how this journey is more than just another adventure to me?, I wonder. What if my whole Camino ends up being a soul-crushing illustration of how an amazing travel experience can be wasted on someone clueless?

The next morning, Amalie tells me that she’s decided to take a bus into León to give her painfully agitated tendon a break and to skip one of the notoriously ugliest, industrial sections of the Camino.

“You should take the bus too,” she suggests, looking at my hugely swollen ankle.

“Never!” I say.

“What are you trying to prove?” she says. “For me, the significant thing about the Camino isn’t the achievement.”

“For me, it’s important.” I say. “I have a real chance here, on the Camino, to be successful at something.”

“Well, don’t forget: Chocolate Factory Day is in four days,” she says. “You need to be able to walk.” For a week, we’ve been anxiously anticipating a visit to the chocolate factory and museum in Astorga, planning to arrive there early in the day while the factory is still hosting chocolate tastings. She’s right that I don’t want a sprained ankle to spoil her chocolate-tasting dreams.

Volunteers give pilgrims free food and juice on a hill in Villares de Órbigo above Astorga, Spain.

For now, we agree to meet at noon in León, and I start walking the unattractive route, past factories, warehouses, and car dealerships, toward the city. I’ve wrapped my ankle in a compression sock, but it’s still so swollen that it’s very painful to walk. I’m too stubborn to stop, so, to distract me from the pain, I spend much of the morning listening to the audiobook of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant, a quirky fantasy novel about an elderly couple who set off on a Camino de Santiago-like journey across medieval England to find their long-lost son. Along the way, a woman tells them a story about a mysterious island that can only be reached traveling alone, and only by ferry boat. The boatman allows couples to travel to the island together only if their bond of love is unbreakable, which he tests rigorously by separating the lovers and asking them individually to recount the most cherished memories of their relationship.

A Camino pilgrim walks toward Crucero de Santo Toribio above Astorga, Spain.

The story captures my imagination enough that I’m able to ignore my sprained ankle all the way to meeting up with Amalie in León for lunch. We spend an extra day drinking beer at a bar on the promenade, visiting the (disappointing) contemporary art museum, and listening to an organ concert in the Gothic cathedral. Knowing that it’s our last planned rest day before Santiago, we spend the evening watching movies and eating bowl after bowl of cornflakes in bed, trying to revel in every possible moment of total motionlessness before the long 11-day push to Santiago.

Flavored chocolate sits in a gift shop in Astorga, Spain.

“Do you think the priest in Santiago is going to test our character somehow before agreeing to absolve us of our sins and give us the Camino completion certificate?” I ask Amalie at night, thinking of The Buried Giant. I’m half-joking, of course, but there’s also a part of me that suspects that a Wizard-of-Oz-like priest in Santiago, hiding behind a tapestry of St. James, will somehow decide that I’m not worthy — that I didn’t learn what I needed to learn on my Camino — that my journey wasn’t spiritual enough. “Do you think he’s going to separate us and ask us to list our most-cherished Camino memories so he can judge them?”

Yellow lupin grows next to the Camino de Santiago on the way to Foncebadón, Spain.

“That seems unlikely,” Amalie says, smiling. “But maybe we should remember every one of them, just in case.”

Two days later, it’s Chocolate Factory Day. Amalie and I excitedly jump out of our beds in Villar de Mazarife at 5:45 AM so that we have a chance of reaching the museum by my guidebook’s listed closing time: 4 PM. Averaging over five kilometers an hour, walking faster than we ever have — Amalie is really, really excited for the chocolate tasting — we fly through the last of the flat, hot, orange Meseta to Hospital de Órbigo, a town defined by a beautiful Gothic bridge which served as the site of medieval jousting competitions. But, the town’s yearly jousting tournament isn’t scheduled for another week, so after a ham sandwich lunch overlooking the bridge with our friends Richard, Danae, and Erin, we push forward as fast as possible. Danae, Erin, Amalie, and I eventually reach a small snack stand on a mountain above Astorga, where we eat the world’s most delicious watermelons and peaches. Then, Amalie and I sprint down the mountain, past a picturesque view of the Crucero de Santo Toribio (a large stone cross) and the Astorga skyline. We’ve walked over 32 kilometers (20 miles) with few breaks when, after a final uphill stretch, we turn a corner and are ecstatic to see the Museo del Chocolate Astorga at 3 PM, giving us an hour to spare before closing. But, seconds later, we spot a sign adjacent to the entrance gate that explains that the museum now closes at 2 PM on Sundays.

Pilgrims gather for tea in the Guacelmo albergue in Rabanal del Camino, Spain.

“NO! They’ve been closed for an hour! That is so typical!” Amalie says as she faux-pounds her head against the museum’s locked gate. She looks devastated. “No chocolate for us.” We sit on a bench together to catch our breath and eat gummy bears. Strangely, even though we’ve been anticipating Chocolate Factory Day for a week, I don’t feel disappointed. Creating another cherished memory with Amalie — a wacky adventure spent sprinting over medieval bridges and eating fantastic watermelon in the Spanish Meseta — even if ending only with gummy bears on a bench — seems just as good.

A single cloud sits in front of a full moon above Cruz Ferro, near the high point of the Camino de Santiago.

The next day, we hike through the rocky, steep Cantabrian Mountains, passing an assortment of stone Celtic villages, wandering cows, and rugged mountaintops, until we reach Rabanal del Camino, a rustic village with traditional, slate-roofed stone houses. In the evening, Amalie and I meet up with the Appalachian Trail guys again over a dinner of bacon, eggs, and fries, and we convince them to leave at 4 AM the next morning to hike with us to Cruz Ferro, near the Camino’s highest point. For centuries, pilgrims have carried stones representing their burdens, all the way from their homes, to the iron cross at the top of the mountain. There, in a ritual both literal and figurative, they leave their stones (and burdens) behind before continuing down. Both Amalie and I have been carrying a rock in each of our bags for weeks in anticipation of this day.

Cruz Ferro, an iron cross atop a wooden pole, stands in a pile of rocks representing pilgrims’ burdens on the Camino de Santiago.

But, at 4 AM the next morning, when Amalie and I arrive at our pre-determined rendezvous point at the edge of town, only Sensei is there to meet us. He tells us that he was the only one of his group committed enough to get out of bed so early. So, the three of us head up the mountain, through the small town of Foncebadón, with the full moon (and the nuns’ paper stars?) guiding our way, until a warm glow slowly begins to appear on the horizon. When we reach Cruz Ferro, the sky is lavender, and a single cloud illuminated in front of the moon looks like a fiery comet shooting through the atmosphere. On the mountaintop, we see a tall wooden pole with an iron cross, standing on a pile of thousands of rocks.

Amalie pulls her stone out of her bag, drops it to the ground, and stares up at the cross and the moon behind it for what seems like an eternity. Then, I join her, pull my stone out of my bag, and drop it on the pile. Standing on a huge mound of symbolic burdens, shed by pilgrims on the Camino over thousands of years, it’s hard for me to deny that the mistakes and failures of my own life seem a little bit smaller.

“This is one of the best moments of my whole Camino,” Sensei gushes as we sit nearby afterward, eating our packed breakfast of Iberian ham baguettes and watching tens of other pilgrims throw their burden rocks below the cross.

“That was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever done,” Amalie says as the sky’s plums and violets change to oranges and golds with the sunrise.

“What a perfect start to a brand new day,” I say. “What’s next?”

God’s dream

Reaching the End of the Earth on the Camino de Santiago.

JULY 30, 2015 — Cruz Ferro was an emotional, spiritual, and physical high point of my trip on the Camino de Santiago, but, in terms of raw beauty, the Camino seems only to improve afterward with each passing day. In Ponferrada, Amalie and I circle around the imposing Templar Residence, a magnificent castle at the top of a hill, complete with a moat, drawbridge, and twelve towers arranged in the shape of the sky’s constellations. In Villafranca del Bierzo, we diverge from the traditional path and tackle the Camino Duro, a rural track over a steep mountain, adding a 1000-meter (3,200-foot) elevation gain and loss — and vertigo-inducing, 360-degree views of the lush Ponferrada valley — to our trip. On yet another mountain summit in the quaint Galician town of O Cebrerio, after enduring a mountaintop hail storm, I spend an evening in a farm field watching a stunning sunset behind the rolling green pastures and peaks of the Cantabrian Mountains.

The Finisterre lighthouse sits at the end of the peninsula.

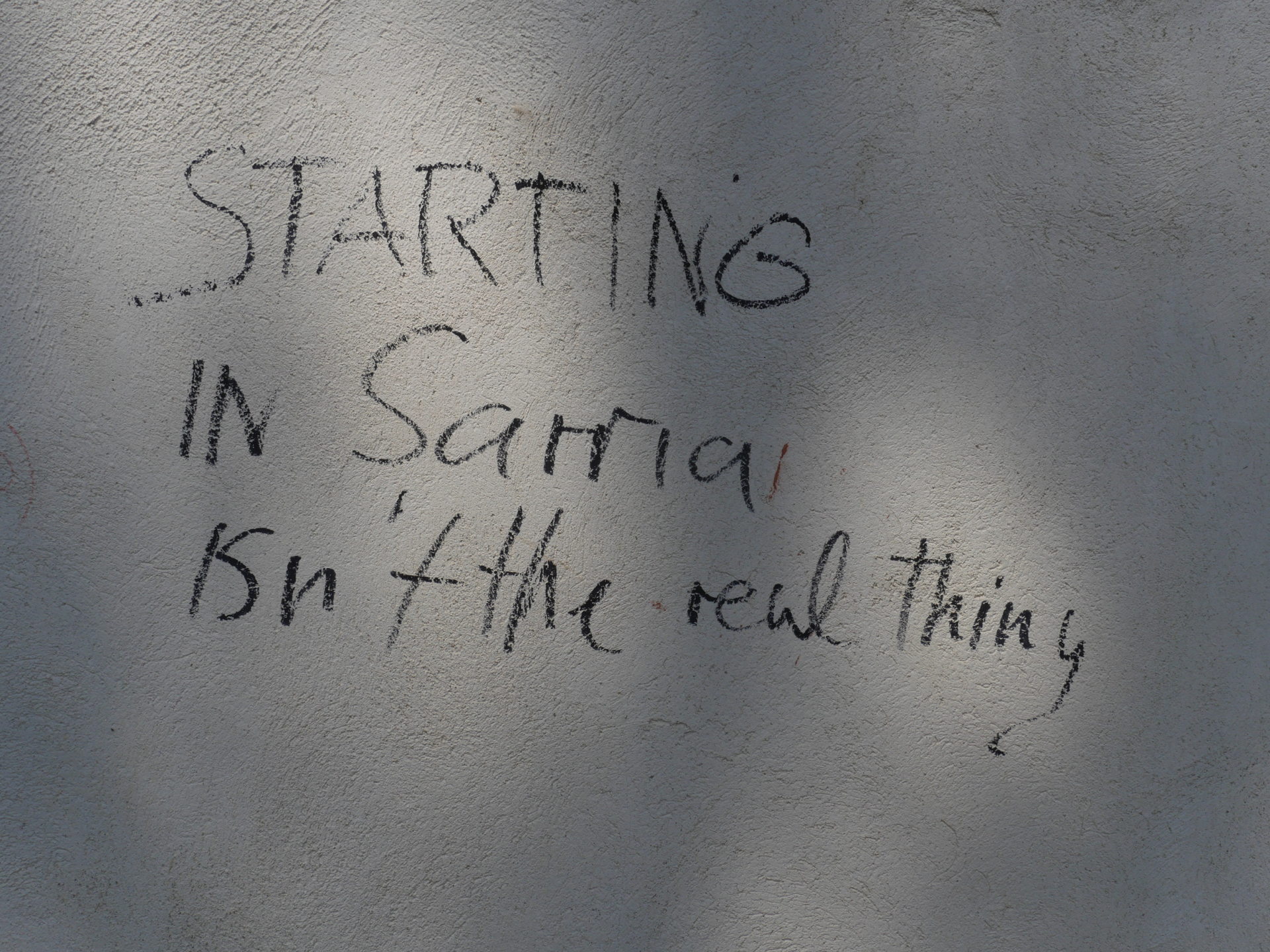

When we pass through Sarria — a small city notable only because it is the starting point for tourists who drop in to walk the minimum 100 kilometers (62 miles) required to receive the Camino completion certificate in Santiago — I spot a stone wall with a message written in black marker: “Starting in Sarria isn’t the real thing.” It makes me laugh. On one hand, the message seems close-minded and mean-spirited. On the other, it taps into a sentiment that both and Amalie and I can’t help but joke about: Who are these loud, obnoxious tourists with spotless, just-purchased REI clothing that think they can just drop in to our Camino and get all of their sins absolved without having to endure 25 days of blisters and hundreds of ham sandwiches?

The Camino Duro gives hikers a spectacular view of the Ponferrada valley.

My cynicism toward Sarria People grows when we arrive in the beautiful, 10th-century town of Portomarín and encounter a large, Italian family in our albergue’s kitchen, playing very loud music and yelling, clearly apathetic about the fact that they’re sharing the facility with nearly 150 other people — many of whom walked over 30 days to get there and just want a good night’s rest. Amalie and I are enjoying a dinner of chicken fajitas that I cooked and relaxing outside the albergue when the family’s patriarch steps outside to smoke near us. I ask him to close the front door behind him so his family’s noise doesn’t disturb the many pilgrims who have moved outside for dinner to escape them.

A sign in a restaurant reminds Camino pilgrims why they’re walking the Camino de Santiago.

“Why? Why do I have to close the door? It’s an albergue! It’s not yours,” he says. He’s clearly drunk, so I don’t say anything else to him, but I can’t help but think to myself: Sarria People are the worst. Later, a 50-year-old German man mentions the “Starting in Sarria” graffiti to me and muses, “I didn’t like that sign. Different kinds of people need different kinds of Caminos to fulfill them, and I don’t judge anyone that made the effort to come here.” When he says this, I realize that I’m not really frustrated with Sarria People personally — though the Italian father was indeed a drunken, selfish jackass. I realize that I’m frustrated by what the presence of Sarria People signifies: I’m nearly to Santiago and less than 180 kilometers (110 miles) from the ocean. In less than a week, my time on the Camino de Santiago will be over.

A handwritten sign near Sarria states, “Starting in Sarria isn’t the real thing.”

Three days later, in total darkness in one of the dorm rooms in our albergue at 6 AM, Amalie and I half excitedly and half reluctantly pack our backpacks for our Camino’s final 5-hour, 24-kilometer (15-mile) leg to Santiago. Our spirits are low as we depart, partly because we’re exhausted from a 38-kilometer (23-mile) leg the day before, and partly because we know that a significant part of our trip is coming to a close. In an attempt to energize us on the way, I invent a singing spoof of the petulant “Starting in Sarria isn’t the real thing” graffiti, to the tune of “She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain.”

“If you haven’t gone to the hospital for your blisters, it’s not the real thing!” I sing. “If you haven’t hiked to Cruz Ferro at sunrise, it’s not the real thing!”

“If you haven’t gotten a symbolic gourd from the Saint of Comfortable Shoes; if you haven’t sprinted 30 kilometers to get to a closed chocolate factory…” adds Amalie.

“If you haven’t eaten ham for 100 meals straight, it’s not the real thing!” I finish.

We relive the best and worst memories of our Camino as we sing ten verses of the song, creating a kind-of informal closing ceremony on our way into Santiago. By the time we’re rushing through the streets of the city, working hard to suppress our desire to eat every bakery goodie we see, we have big smiles on our faces. Soon, we hear a bagpipe player and then pass through an archway to the Praza de Obradoiro, a large plaza facing the Santiago Cathedral’s iconic western facade, where we head directly inside to catch the noontime pilgrim’s mass. All of the pews are full, so we stand in the back of the church together. In Spanish, the priest talks to the crowd about the importance of doing the pilgrimage, and then, everyone walks forward to receive a wafer of sacramental bread. It’s clear that the ceremony itself means much more to the Catholics in the church than to me and Amalie, but, nevertheless, it’s quite moving to see all the Camino pilgrims around us — many of whom have knee braces, legs covered in elastic tape, and trekking poles to support them — congratulating each other, hugging, and crying out of joy. It’s like watching 1,000 people all have the best moment of their lives, simultaneously, right before our eyes.

A statue of St. James sits atop the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral.

When I get to the front of the line to apply for my Compostela — the certificate that proves that someone walked the Camino de Santiago — I proudly present my Credencial del Peregrino (pilgrim’s passport), which contains a stamp from every albergue in which I stayed overnight on the Camino, validating my claim that I walked over 800 kilometers to get to Santiago. Keeping in mind the lyrics to Amalie’s and my song-of-memories from the morning, I also get ready to enumerate every cherished memory from my Camino, to prove that I really completed the trip.

A man hugs the statue of St. James in the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral.

“Wow, Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port,” the clerk says, noticing my starting point. “Congratulations! Your motivations for walking the Camino — were they religious or spiritual?” he asks. “Spiritual,” I say. To my surprise, he immediately hands me a Compostela with my name on it, without even asking me to describe a single cherished memory from the trip. I look over at Amalie who has also just received her certificate, and I realize that there is already a person in the world who can corroborate my trip, because she knows the details of each one of my cherished Camino memories. It’s enough for me.

A woman prays in front of the tomb of St. James in the basement of the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral.

Afterward, Amalie and I stop at Camino Companions, an organization that invites pilgrims to discuss the meaning of their Camino experiences at the end of their walk. There, with a nun named Katherine who walked part of the Camino the year before, we spend an hour discussing our journey. We talk about whether travel can change you, the joy of open and empathetic new friends, the fleeting nature of relationships on the Camino and in life, how slowing down can help you live in the moment, and how spending time away can help you see your life from a new perspective.

A group of friends hugs in the plaza in front of the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral.

“The hardest thing about leaving here is going to be returning to the ‘real world’ where people tend not to be as friendly, open, and honest on a daily basis,” I say.

“It’s going to be difficult to go from seeing all the people I’ve met here every day to maybe never seeing them again,” Amalie says. “I wish I knew how to continue this feeling.”

“Over the next few days, you should think and talk together about how you might take some of the things you learned here back home with you,” Katherine says. “Personally, I have a feeling that the Camino is God’s dream for how people should be when they’re with each other.”

A Camino pilgrim reads a book next to the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral.

Amalie and I spend much of the next two days lying in the plaza in front of the Santiago Cathedral, watching pilgrims arrive in Santiago for the first time, over, and over, and over. Many cry, some yell and cheer, some look up at the church spires in silence and disbelief, and some collapse on the ground. Though some of our best friends from the journey walked faster than us and have already left Santiago (like American, sunburned Katie; the adorable, in-love couple Hannah and Arnaud; and the Chilean and American duo, Danae and Erin), others manage to find us while we bask in the overwhelming shadow of the Cathedral. Canadian balloon-animaler Brock hugs both of us the moment he sees us. Polish married couple Jerzy and Sylwia look utterly relieved to not have to walk anymore. A 70-year-old Belgian couple with whom we’ve shared many albergues stares at the cathedral without saying a word with tears streaming down the wife’s face — they started the Camino from their front door in Belgium and walked 2,500 kilometers to get here. And the Appalachian Trail trio — Hammer, The Professor, and Sensei — tell us they’ve decided to finish their trip with a bus trip to the sea.

A stone marker labeled “0.00 K.M.” marks the end of the Camino Finisterre at the end of the peninsula in Finisterre.

Of course, my Camino dream has always been to walk all the way to the ocean. So, the next morning, Amalie and I leave Santiago on foot to walk the final three days to Finisterre — the rock-covered peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean whose Latin name means “the End of the Earth.” The trip isn’t any physically easier than the rest of the Camino, but, somehow, it feels like we’re on a lighter, happier, more vacation-like walk.

A Camino pilgrim lays on a rock looking at the sunset over the Finisterre peninsula.

In the afternoon of the third day, we crest a hill above the town of Cee and see the Atlantic Ocean for the first time on our trip from the high vantage point. We both yell out in pure joy. Just two hours later, in the pouring rain, we arrive at a beach in Finisterre. We drop our backpacks on the sand, take off our shoes and socks, and sprint across the beach and into the freezing ocean. In the evening, as the sun is setting, we arrive together at a beautiful lighthouse at the end of the peninsula. Past the tower, we walk onto a steep, rocky crag that falls off into the sea. Ahead of me, Amalie sits down on a boulder.

She doesn’t know it, but as Amalie sits, lost in thought at the End of the Earth, staring at the murky, golden sunset over the ocean, I’m crying behind her.

I’m not a religious person, but remembering everyone I’ve met in Spain and looking out at Amalie, I’m sure that the nun in Santiago was right. The Camino is God’s dream for how people should be when they’re with each other — and I’m heartbroken that we’re about to wake up.

How to Hike the Camino de Santiago Francés

OVERVIEW: The Camino de Santiago Francés is a 880-kilometer (540-mile) walking trip across Spain, connecting Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in France to Santiago de Compostela and Finisterre in Spain.

ROUTE: View the route below or download the Without Baggage Camino de Santiago Francés GPS track in GPX or KML format.

I am loving your descriptive writing. I need more. Where are you?

Tough to read this entry. I had some pretty bad blisters, and jettisoned my boots in favor of sandals and cross-trainers. Compeed saved me for the rest of the trip. Funny, I have a photos of a foot clinic in Estella, the only one I saw. Good luck. It's worth the pain. Everything you say about people coming and going is true, but the Camino is an ever-flowing stream. Enjoy it.

The memories of my walk were awaken by your words. Thank you. Your story made me cry for some reason. a pouring out of emotion.

This is a great read. I am patiently waiting until June of '16 when I can begin my Camino.

Reading your blog harkens me back to my own Camino experience-I was so focused on resolving the reason for my making the pilgrimage that I never saw any of the things you describe even though we trod the same path. Happily, my pilgrimage was successful and I returned with a peace I have never know. It has been 10 months since my return and each day I feel more content, stronger, at peace. I will be returning to the Camino in late September, 2016-have no goals for the Camino this time-at least not at this moment-but am open to whatever the Universe has for me. Thank you for sharing your experiences.

Hank! I think I've read this final essay about the Camino 3 times already and the moments that you've captured have had me giggling for days… and of course the ending made me cry. You've articulated so well how I feel about the experience, so thank you for giving me the words on paper to express my feelings!

Nice, nice, nice, great, great, great.

I linked your video to my weblog on Pilgrimage and Camino.

The Pilgrim's Gaze 😉

All the best on your way forward!

Oh my goodness! I'm so excited!! Now I get to read this entire series with all the juicy details from your movie. It's like Christmas morning finding this! You are an excellent writer. Thank you for feeding my Camino addiction as I dream of the day I will finally walk the Way of St. James…

OK. I winced the entire time I read this entry. Yikes. I definitely want to avoid blisters happening to me at all costs. It seems that hiking boots are definitely not the correct footwear for the Camino.

I did the Camino in August 2015. This post and your video were amazing to watch, it brought back so many memories. I'm just super curious, did you and Amelia ever end up together, are you going to? The suspense is killing me.

Ruth, Paul, Holly, and Taren: Thank you so much for your thoughtful compliments! I'm really glad you enjoyed the story of my Camino.Holly, I can't wait to hear about your Camino!

I just stumbled upon your camino film… Well done! I walked the camino last year . I had lost my wife the prior year and i just felt like going for a hike….. A long hike. It brought back such incredible memories for me. I too met the most wonderful, beautiful, incredible woman and I fell in love with her . It was difficult to say goodbye and even though we live in different countries we have visited each other and I lhope to walk it again with her!!!!!

Thank you, al

Have you written more about your Camino? If so, where would I find it? I loved watching your video.

Albert: Thanks so much for your kind words. It's great to hear your story — I'm happy you had a great Camino also!

Karen: At the end of each Camino post I wrote (I wrote 5) is a link to the next part of the story. Hope that helps!

Thank you for making this movie. I like real stuff, so I was very happy with your documentary. It is way better than the movie The Way for me (more pilgrims to come on the Camino Francés due to you ?!)

Great video, curious where you flew into Europe to get to Bayonne? Does it makes sense to fly into Madrid? thanks

Hi Roland! I flew into Paris (CDG), took a train to Bayonne, and then a bus to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. At the end of my trip, I flew from Santiago de Compostela to Madrid to fly out of Spain. I kind of liked the idea of taking a train across France and literally walking across the border into Spain myself for my first entrance in Spain, which is part of the reason I did it this way. Also, there's something nice about taking a train through France.

Hey- I have been showing your video to many people as it captures something incredibly joyful and moving at the same time. Thank you so much-

Yeah I love your website with the travelling and this series in Spain is fantastic!

I'm hiking a lot in the US and I'm planning to take a half year break next year.

Hiking Tom.

I'm six days off from completing the Camino (10/14) also ending by foot to Finesterre; then drove to Muxia to complete the journey (note: it took us 55 days, which includes 8 rest days). Thank you for your story and video. I tried to take pictures but was not able to capture the beauty of the landscape and charm of the Camino. Buen Camino

Great writings, stories, and film. As Amalie I to learned of the Camino from the movie The Way. You have just reenergized me to do this.

Thank you.

Hi Hank,

Thank you for the video. I've only recently been drawn to the Camino and a believer in Synchronicity I found your blog and video. I plan to start slowly training for the hike after being inspired by learning people of all ages do the trail. It will be a spiritual journey for me and I hope to be as successful as you were with your journey.

Regards,

Heather , Canada

from hank to hank.that was sensational.i have just walked the kokoda track in papua new guinnea.i now want to walk the camino.dont give up making films.you are a gifted special person and thankyou for letting me share your experience.cheers hank

Hank,

Thanks for a wonderful film. I walked the CF in 2013 and the VdlP this year and will do it again in march 2016. Fabulous film, honest and well edited. But… how are things with Amalia? Inquiring minds want to know.

Thanks

Steve

Gracias amigo por el gran reportaje del camino de santiago,he vuelto a revivir tu pequeños problemas con los pies que al final del camino se convierten en anécdotas sigo recordando el camino como si fuera ayer, como veras sigo viendo videos, una de mis promesas es que cuando me jubile a los 61 año vuelvo al camino….gracias por todo desde ESPAÑA

yesterday i finished reading the recommended book, The Buried Giant 😀

What happened to the lovely Danish girl you shared the walk with??

Hello Hank, thanks for the nice video it brings me back the memories . I did The French Way in June 2012 and then from Santiago to Muxia and at last to Finistera. This year I will do the Camino Primitivo . June 01, 2016 I'll start from Bilbao and try to go further from Santiago to Porto ( Portugal ).

What shoes did you end up buying on the camino that made all the difference, I am scared my goretex ankle support boots I normally use are not the right choice for a journey such as this

"How people should be when they are together." That Nun said it perfectly. Buen Camino on the rest of your journeys. I hiked the Camino last July and as we followed our last shell into the square, my boyfriend at the time, got down on one knee and asked me to marry him. Thank you for sharing your adventure.

Hank -Seems like Amelie was a very integral part of your Camino experience and beautiful to boot! What became of her and are you still in contact with each other? I'm trying desperately to get over and experience the walk for myself.

Dear Hank,

We never met, but we have been walking the same path.

Thank you for your words, for every scene that heart can see further, for every sound that heart can hear clearer, for every sensations that disturbs the depths. That is the path (camino), the truth and the life. The vows engraved in the stone, sparks that light up our days, silent presence that warms with hope.

The signs to follow and the gift to be reflected farther. The answer is just one and the only thing.

Buen Camino and all the blessings,

Barbara

Ok i’ll Ask the “elephant in the room” question, what happened between you and Amelie, The chemistry seemed to be screaming out of the screen and she seemed so likeable it was like watching bambi ( sweet, likeable and just having such a presence on screen) even if you didn’t partner up I would watch anything that you both appeared in.

Hola HAL! Muchas gracias for all your posts – rich material. More power to your inspired writing. Like your narratives, so creative…(As for me, am still deciding if I could be as brave to share my stories and reflections.)

Just finished my first camino last Oct 08 to celebrate a milestone birthday. Praying it would be possible to go back again someday. Have not gone to Fisterra-Muxia yet. Looking forward. Ultreia!

DIOS TE BENDIGO!

Lovely story….but dying to know what happened between you and Amalie? Looked like you were true soulmates?

Hank: after watching your documentary i thnki i will invite my wife to try it together. I am a very romantic person and you meeting Amelie was a great point on your trip. Thanks for sharing this with us.