DECEMBER 13, 2011 — I’m walking down a street lined with noodle shops in Shanghai. I’m hungry, but all of the shops’ signs are written with Chinese characters, so there’s no way for me to tell one from another. I pick one at random. Inside, I find a small room with white, concrete walls and black and white, flower-printed lanterns hanging overhead. The restaurant is crowded, but one wooden table is empty. Since I can’t read the menu on a sign above the cashier, I order by pointing at one of the promotional pictures on the wall.

The hostess seats me at the empty table, but within a minute, she seats a Chinese couple with me. We greet each other (“Ni hao”/”Ni hao”) and then sit awkwardly, waiting for our food. I’m immediately frustrated by my inability to speak Mandarin. Even when I’m not in China, I hate myself for so many reasons: avoiding the gym, gorging on cheese, forgetting to water my living room plant, being unable to affect accents, screwing up on my life on a daily basis, and then dwelling on those screw ups. The list is endless. But the hate I harbor for myself for not being able to speak Mandarin in China is uniquely frustrating. I’m frustrated that the only pre-college languages classes offered to me were Spanish, French, and German. (In retrospect, the short-sightedness of American school administrators when I was young is terrifying, considering that, today, more native speakers speak Mandarin than speak English, Spanish, German and French combined.) I’m frustrated that Chinese is such a difficult language to learn. But, most of all, I’m frustrated that I feel like I’m the rudest person in the world, wandering around a foreign country without having learned enough of its language to have a respectful conservation with a couple in a restaurant. I incompetently fumble with my chopsticks as we eat our unidentified (but tasty) Chinese food in silence.

The hot springs resort, covered in snow, near Huangshan.

On the following afternoon, I’m surprised when the bus I’ve taken from Shanghai to Huangshan (China’s famous “Yellow Mountain”) drops all of its passengers in front of a newly-built hotel on the outskirts of town. This bus-driver behavior is a frequent ploy to get tourists on the bus to stay at the hotel, but I’m the only Westerner on the bus, and everyone gets off with me. So, I don’t know what to think.

A sign advertises White Goose Villa as the Best Photographic Point of Mount Huangshan.

Instead of being the sleepy mountain town I expected, Huangshan turns out to be a huge, modern resort town amidst major construction. This isn’t a huge surprise to me: across China, it seems, everything — every road, hotel, restaurant, and train track — looks like it’s being built or rebuilt. It occurs to me this is what a major industrial revolution and economic boom looks like in Communist country that has turned to capitalism (known in China as the “economic miracle” or “Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics”).

I’m sitting in the hotel’s lobby trying to decide what to do next when a short, pudgy Chinese woman with a beaming smile, sitting with her tall boyfriend on a couch, says to me in weak English, “You staying at hotel?”

“I haven’t really decided,” I say. “Are you staying here?”

“Yes, my boyfriend booked it online for us this weekend.” she explains. “The rate very good and room nice. You stay here with us!” She says something to the xiaojie working at the desk — hotels, restaurants, and shops in China are staffed almost exclusively by pretty, young women often referred to as xiaojie — and she takes me to see a room.

“Good, yes?” says the woman on the couch when I return to the lobby. “I will help you check in to the hotel. This is my boyfriend Ricky, and I’m Meggie: like Maggie, but I put an ‘e’ in it.” (Even Chinese-speakers in mainland China usually have both a Chinese name and a self-picked English name that they use when speaking English.) I immediately like the couple, partly because of Meggie’s name creativity but also because the hotel rate they’ve negotiated for me is great (about US $20 for a room of a quality that would go for $150 in a US city). Meggie goes on to help facilitate my entire transaction with the xiaojie. I can’t overstate how helpful small gestures like this from (even weak) English speakers are, turning my travels in China from a train wreck into, well, a smaller train wreck.

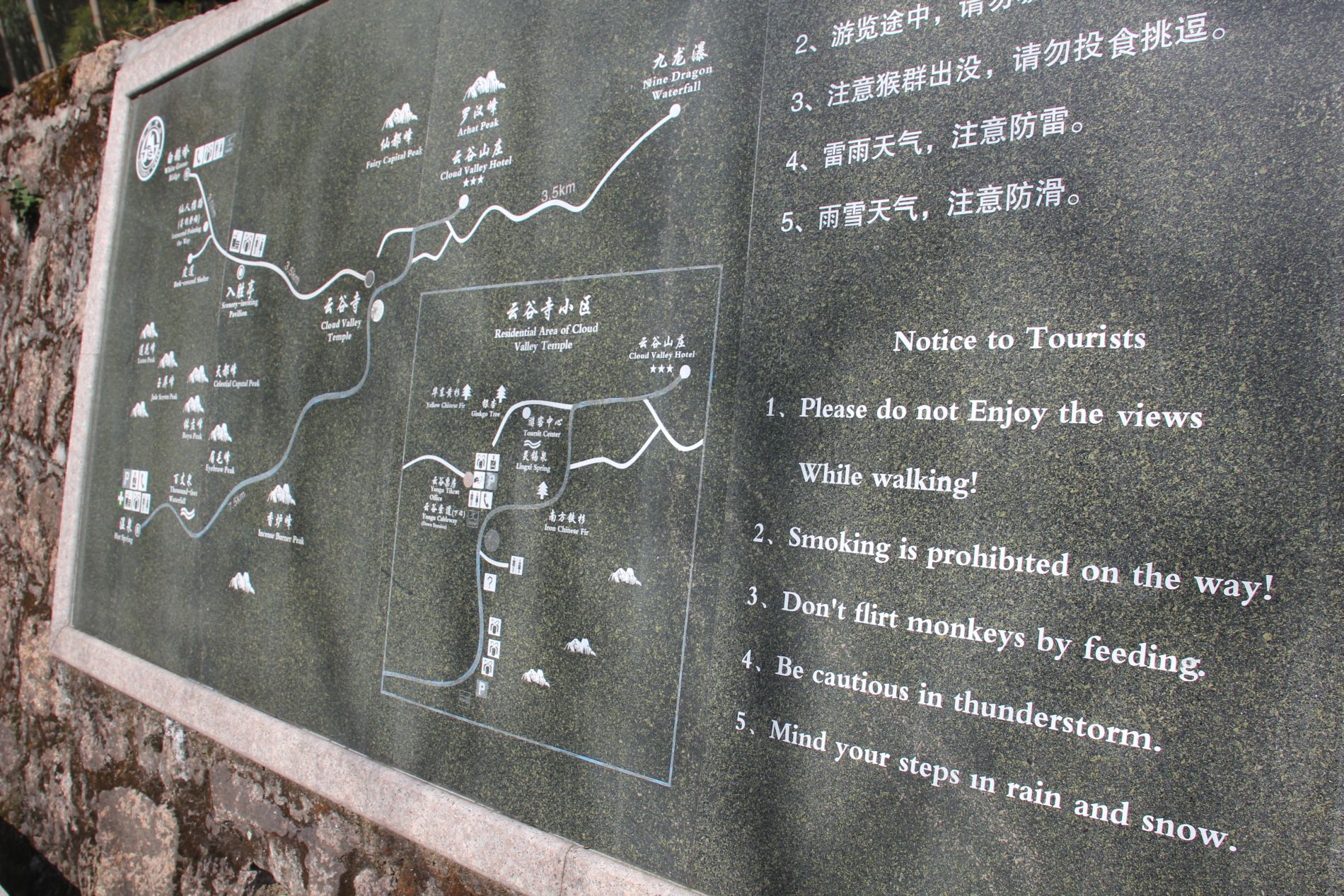

A sign warns Huangshan hikers to “not enjoy the views while walking.”

“We going to hot springs now,” Meggie demands. It’s clear that her “we” includes me. I look at the drab, overcast sky above Huangshan and decide that tomorrow might be a better day to start my two-day hike up and down the mountain anyway. Meggie thankfully arranges for the hotel driver to take us to the nearby Best Western-run spa resort with a bunch of outdoor hot springs pools. It’s snowing outside, but Meggie and Ricky drag me from one pool to the next: one’s vinegar-infused, another’s red wine-infused, and one’s even filled with small fish that bite the dead skin off of your feet. (No, I don’t understand it either.) I keep trying to give Meggie and Ricky some privacy, but they keep insisting that I follow them from pool to pool.

A porter carries food and supplies to hotels atop Huangshan.

“Get your free melon and other snacks over there,” Ricky tells me. “Then we’ll try the wine pool and get Chinese foot massages!” I’m the child not yet able to speak, and Ricky and Meggie are my fun, Mandarin-fluent parents. I’m not complaining.

But, like most parents, Meggie and Ricky want to wake up much earlier than I do to start hiking the following day, and they plan on spending only one day on the mountain. So, we part ways, and the next morning, I begin climbing the thousands of stairs that make up the eastern path up Huangshan. The deep vistas of wispy fog rolling across the valley, circling the jagged, blue peaks of Huangshan keep me occupied, though the climb is relentlessly steep and I can feel the freezing air (it’s about 25°F) seeping through my skin. It’s hardly an ideal wilderness experience, also because I’m surrounded by flabby Chinese tour groups, led by obnoxious tour guides with bullhorns using cable cars to get their followers up and down the mountain. Huangshan’s scenery is beautiful, but I’m disappointed to see that China’s current environmental ethos is on par with America’s (now changed for the better) 1950s National Park philosophy: build hotels, pave the wilderness, herd tourists like cattle, and scare away wildlife.

Chinese tourists admire a view near the summit of Huangshan.

About halfway up the mountain, I see a sign reading, “Best Photographic Point of Mount Huangshan.” It’s so cold and I hear so many bullhorns that I’m tempted to take the “best” photo and head back down, since the views apparently won’t get any better higher up. But my willpower stays strong. About ten minutes later, I come across another “Best Photographic Point” sign. Okay, which is it?! I think, and set up another photo. Then, a few minutes later, I see yet another sign, and I realize that the mountain is covered with “Best Photographic Point” signs. Apparently the translator didn’t know the difference between “best” and “recommended.” Incidentally, China has, hands down, the funniest badly-translated English signs that I have seen anywhere in the world; my other Huangshan favorites are: “Congratulations for your children growing taller” on an entrance sign defining the height limit for kids’ tickets; “Please get closer to the urinal” in a public bathroom; “Don’t flirt monkeys by feeding”; the dubious “Leave your virtue in Huangshan and the scenery in your memory”; and the forceful “Please do not enjoy the views while walking!”

The sun shines on a particularly beautiful day on Huangshan’s Bright Summit.

My progress up the mountain is especially slow because Chinese tourists (even grown men) frequently stop me to ask if I’ll pose for a picture with them. (As far as I can tell, I’m the only Westerner on the mountain). When I finally arrive at the top, it’s almost dark, and I’m starving, exhausted, and cold. Unfortunately, the handful of summit hotels are all closed for construction or booked by the bullhorns. I wander around the summit, begging hotels to give me a room, when, finally, I find a bed in a six-person dormitory in the Baiyun Hotel. I’m totally drained when I open the door to the room and find four other Chinese men hanging out, watching Chinese television and hocking loogies. I’m hiding from them under my bunk bed’s quilt, letting the sound design of the iPhone’s “Sword & Sorcery EP” game try to soothe my misery, when another Chinese man’s head pops up in front of my face.

“Hank?!” he asks in disbelief. It’s Ricky, who has, by coincidence (or fate?), found the last room with the last empty bed on the mountain. “We were too tired to walk back down today. We getting dinner!” I know he means me too.

Ricky and Meggie lead me to one of the restaurants in the hotel: “This one’s cheaper but they make us the same food,” Ricky says. My Chinese parents order me something mostly unlike chicken noodle soup. I admit: the food and the company makes me feel better.

“We getting up at 6:00 AM to see the sunrise,” Meggie announces. I don’t really have a choice; they’re my Chinese parents.

At 6:45 AM the next morning, the three of us are standing under a pagoda on a high summit above the hotel, but there’s so much fog that the sun is still nowhere to be seen. We begin walking down the mountain together. The two of them get ahead of me for a while because I’m exploring some side trails, but we eventually meet again at the cable car station about halfway down the mountain. Meggie’s face makes it’s clear that she’s done hiking in the cold.

The “Greeting Pine” welcomes tourists who arrive on Huangshan by cable car.

“We taking the cable car,” Meggie says. I shake my head. I tell them that I really want to hike the rest of the way down. This time, we know we won’t see each other again. We take a photo together at the Best Photographic Point of Mount Huangshan.

“Good luck,” Meggie says, sadly. “Without us, you must learn to speak Chinese.”

“I know,” I say. “Thanks so much for all of your help. Be sure to leave your virtue in Huangshan.” She looks at me, puzzled, as though she thinks her English has failed her. Then, I watch them get into their cable car, and I continue hiking, trying my best not to enjoy the views while walking.

Further down the mountain, a six-person Chinese family stops me at the Best Photographic Point of Mount Huangshan to take six photos with me (usually, each family member likes to have his own). Afterward, without explanation, they pull assorted Chinese foods out of their backpacks: boiled eggs, kebabs, shaobing (sesame seed cake), Chinese jerky, and foreign candy.

“Eat,” one of them says. Though I’ve already eaten, I know that these new Chinese parents will be as equally stubborn as Meggie and Ricky. I sit down and begin with a bite of shaobing. Everytime I try a bite of a new food, the family laughs when they see my expression. I laugh too.

I’ve never met these people. I don’t know what I’m eating. We can’t talk to each other. But, somehow, I’m not frustrated anymore.

How to Hike China’s Huangshan (Yellow Mountain)

OVERVIEW: China’s Huangshan (Yellow Mountain) is one of China’s most beautiful and inspiring sights, an outdoor paradise consisting of jagged granite peaks and gnarled pine trees enveloped in blankets of fog. Yet, like so much of China, the surrounding area is all but ruined by mediocre hotels, restaurants, and overdevelopment; the mountain itself is overrun by loud, inconsiderate Chinese tour groups using bullhorns; and the “hiking” trails are paved with stone staircases. Walking up and down the mountain is only a 22.5-kilometer (14-mile) round trip, but the over 1000-meter (3,280-foot) elevation gain will test the knees of even the most fit hikers. For those not up to the challenge, cable cars take visitors (and large gaggles of Chinese tourists) up and down the mountain.

LOGISTICS: The fastest way to get to Huangshan is to take the one-hour flight from Shanghai to the Huangshan airport (in nearby Tunxi). You can also take the bus from Shanghai (6.5 hours, Y120/US $20). In Huangshan, you can buy a (still cryptic) English hiking map of Huangshan at any store. From your hotel, walk or take a taxi to the Huangshan bus station to buy a ticket for the shuttle to the Yungu Cable Car Station (eastern steps) or Mercy Light Temple Station (western steps) to start your hike. If you can’t speak Mandarin, just point to the Yungu Cable Car Station on your map to buy the ticket. Regardless of whether you want to use the cable cars, admission to the mountain is a ridiculously expensive Y230/US $36 or, from December to February, Y130/US $20.

ROUTE: Though this hike can be done in one day, taking two days to hike the circuit will make the experience more enjoyable. Hiking up the eastern steps (7.5 km) and down the western steps (15 km) works best. Both routes in both directions are exhausting due to the big elevation changes, but going down the western steps is a bit easier than going up them. If you take three days, you should include the 8.5-kilometer West Sea Canyon hike on the top of Huangshan (just follow the signs), which Chinese tour groups avoid because of the route’s difficulty. (Unfortunately, this section of trail is closed in snowy or icy conditions.) View the route below or download the Without Baggage Huangshan GPS track in GPX or KML format.

I'm taking mandarin classes at work (once a week), and it is so hard and discouraging. The language structure itself is really easy (no conjugations, no tenses, no plurals, etc.) but it requires sounds we don't use or distinguish in English (or any Western language), and has nothing at all in common with any Western language. And the writing is impossible for anybody to learn.

Google translate does a fairly decent job of translating into Chinese, you can try that for some key phrases.

I'm really jealous that you're taking Mandarin classes. I really would like to take a shot at it sometime because I really like just looking at the characters. I have been using the Google Translate app a huge amount on my phone; I'd probably be dead already without it.

Dear Hank,

I've been secretly following your website for a while now and just wanted to tell you I truly enjoyed this post!

Happy travels,

Inbar.

I was doing research on biking in Anchorage and wound up here, reading about your travels to China. I really want to know if you got together with your ex-girlfriend after Honduras, married, with kids, or at least one on the way. Really good blog. I got lost in it and dreamed…

Hi, Jina: Glad you're enjoying the blog! You're not the first who has asked about the ex-girlfriend I won back in Honduras. I prefer to keep the events following our time in Honduras private, but I'm sorry to add that, as I'm sure you can extrapolate from essays since then, we're no longer together. Sorry to disappoint!

Came upon this post while researching about Huangshan for an upcoming trip and wanted to let you know that I was surprised at how much I enjoyed your writing. 🙂

This post was amazing and genuinely made me laugh. Love your description of what to expect! We are going to Huangshan next September and look forward to hiking. (if not the crowds) Thank you for your beautiful words!