MAY 10, 2011 — According to an ancient legend from the 15th century, Vietnamese Emperor Le Loi, the founder of Vietnam’s Le Dynasty, encountered a holy turtle on a boat cruise across Hanoi’s Luc Thuy (Green Lake). The magical talking turtle demanded that the Emperor return a sword that he had taken from Kim Qui, the Golden Turtle God, to help defeat Chinese invaders. The Emperor — likely terrified by the threat of a talking turtle — unsheathed the sword, threw it into the lake to the turtle, and renamed the lake Hoan Kiem (The Lake of the Returned Sword).

Vietnamese families watch the Hoan Kiem turtle surface in Hanoi’s Green Lake.

I’m unaware of this ancient legend when my mom (yes, the Extreme one) asks me if I would like to bicycle across Vietnam and Cambodia during Christmas vacation. I’m a little surprised by this request, but, because my father passed away this year, I know that neither of us are excited to celebrate Christmas at home in our traditional way. Escaping the country on a bike seems like a great way to get through the holiday. A week before Christmas, I leave India to meet my mom in Hanoi and check into the Sofitel Metropole Hanoi. The fantastic hotel was featured in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, a classic novel about a journalist living in Vietnam during the French Indochina War. After two weeks in Indian budget hotels, I feel like I’ve become a Slumdog Millionaire overnight.

The Hoan Kiem turtle surfaces in Hanoi’s Green Lake.

It becomes clear quickly why Greene liked the hotel so much; my mom and I spend the night by the pool, listening to a talented French-Vietnamese singer with a silky voice entertain the bar with standards from the 1950s. In the morning, we decide to go shopping in Hanoi’s Old Quarter to find gear for me for our bicycling trip. (Because I have come directly from backpacking through Nepal and India, I only have hiking boots with me — definitely a liability on a bike.) We walk down narrow Old Quarter streets, each conveniently organized by product: there’s a clothing street, a flowers street, a hardware street, and, thankfully, a shoes street. Unfortunately, finding a pair of sneakers in size 11 in Vietnam — a country where the average height is five feet, five inches — is not easy. We visit a handful of shoe stores, all of which carry low-quality, counterfeit brand name shoes made in China. At each store, a female, five-foot tall shopkeeper laughs when I point at my feet and then usually points to a single pair of shoes that almost — but don’t — fit. I feel like I’ve been cast in a new sitcom titled Gulliver’s Travels: The Communist Years.

Traffic and a mural pass under Hanoi’s historic Long Bien Bridge.

The ugly shoes that I find finally for US $50 look like they will last me two weeks before falling apart; fortunately, that’s as long as I need them. After we visit a few more stores to find some athletic socks (yes, on a socks street), we walk back toward the Metropole along the shore of Hanoi’s Luc Thuy.

A large group of Vietnamese families gathered along the shore catches our eye, and we stroll by them to see what we’re missing. At first, they appear mesmerized only by Green Lake. But, when we look more closely at the water, we catch sight of the Hoan Kiem Turtle, popping out from beneath the surface. This is an unbelievable event, because the Turtle is seen so rarely that it was once classified as cryptozoological — pseudoscientific, like the Loch Ness Monster. But, in 1998, a photographer caught the animal on video, proving its existence. We watch the turtle and the awed gawkers for a while and then head back to our hotel. When we arrive, we meet our cycling group: Stew, Shelley, Cliff, Bill, and Teng — our bicycle trip leader. I notice that I’m the youngest cyclist on the trip by at least 20 years. Excitedly, my mom and I tell everyone that we saw the Hoan Kiem Turtle in the Lake. Teng is stunned.

A young girl rubs the head of a statue of the Hoan Kiem turtle in Hanoi’s Temple of Literature.

“I’ve lived in Hanoi for my whole life, and I’ve never seen the turtle,” he explains, disappointed. He tells us that the turtle is thought to be centuries old and says that university students rub the heads of stone statues of the turtle to help ensure that they pass their exams. “The fact that you saw the turtle… wow. That’s very good luck.”

Ho Chi Minh’s cryogenically frozen body lies in a mausoleum in Ba Dinh Square, Hanoi.

It’s an auspicious beginning to our bicycle journey across Vietnam, and my mom and I start pedaling through Hanoi buoyed with feelings of optimism and confidence. In a year filled with bad news for our family, it’s a much needed reprieve.

Teng and a local professor of Vietnamese history take our cycling group to Hanoi’s historic Long Bien Bridge, which connects Hanoi to port Haiphong across the Red River. The professor explains that Americans bombed the bridge repeatedly with the world’s first laser-guided bombs during The American War (the Vietnamese name for the Vietnam War), but Vietnamese workers repaired the bridge with whatever decidedly low-tech supplies they could find: rocks, steel ties, and lumber. The professor also tells us that the Bridge illustrates the resourcefulness and steadfastness of the Vietnamese people defending their homeland during the War. He doesn’t mention the South Vietnamese army, instead preferring to frame the war as a conflict between the “Vietnamese people” and Americans. I’m a bit shocked to hear this description, considering the way the conflict is painted in American history books, but it’s an eye-opening perspective.

A woman makes paper by hand in Dong Ho, Vietnam.

We make quick stops at Ho Chi Minh’s Mausoleum (a tomb in which tourists can see Ho Chi Minh’s cryogenically frozen body), the Ma May museum in the Old Quarter (a restored, traditional Vietnamese house), and the Temple of Literature (the country’s first university). As Teng predicted, inside the university gates, my mom and I see a young girl rubbing the heads of stone statues of the Hoan Kiem turtle for good luck. I want to tell the girl that she should rush directly to Green Lake to see the turtle and share in our good luck, but I don’t speak Vietnamese.

A woman works on paper votives in Dong Ho, Vietnam.

On our second day in Hanoi, we pedal to nearby Dong Ho, a village known for its traditional Vietnamese woodblock prints. Teng takes us into a shop selling the beautiful designs, and we watch a woman working tirelessly, making traditional Vietnamese paper. Afterward, Teng leads us through the rest of the village, where we catch a glimpse of a warehouse filled to the brim with shoes — except, strangely, they’re fake shoes, made of paper.

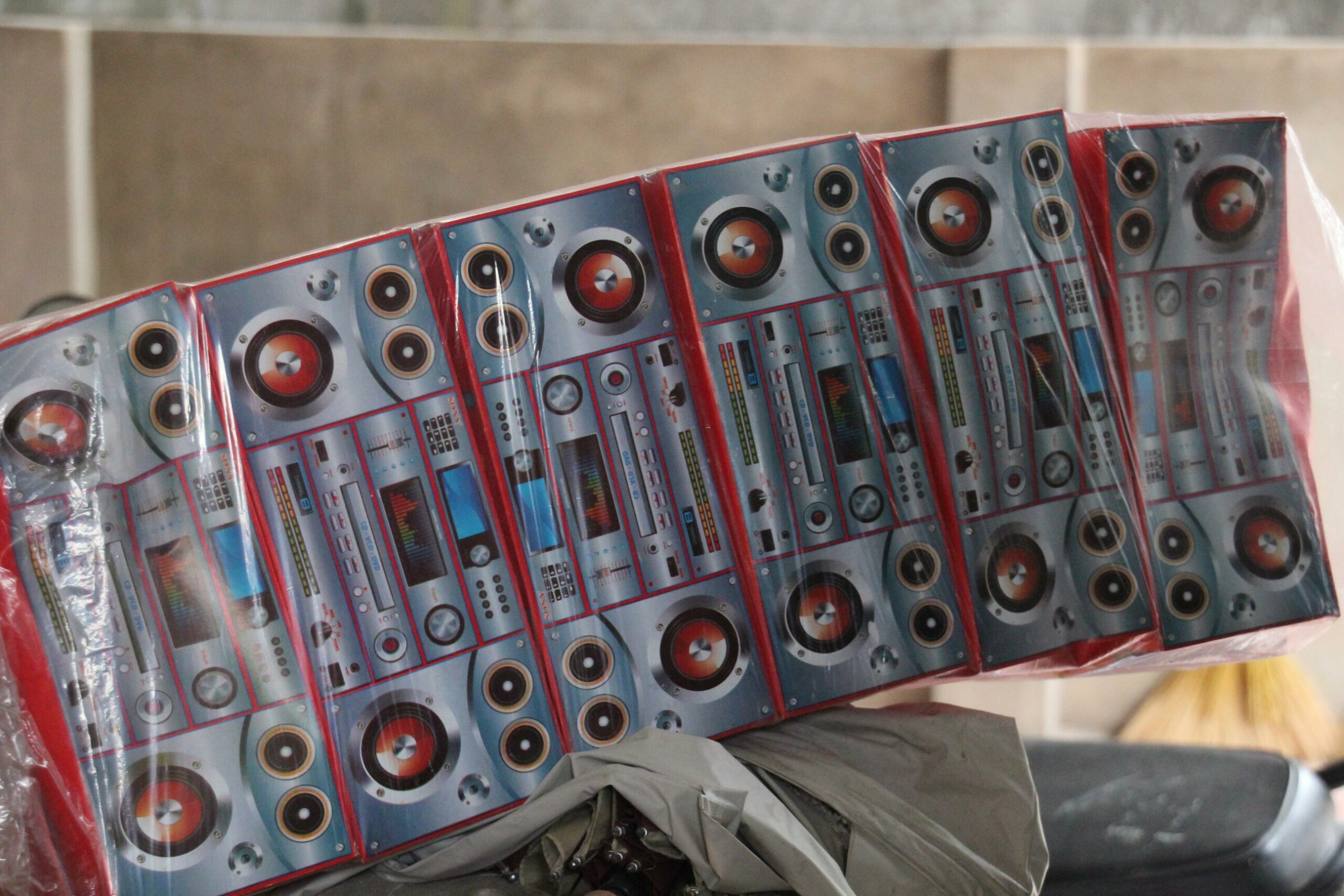

Votive (fake paper) stereo systems are among the products manufactured in Dong Ho, Vietnam.

“They’re votives,” Teng explains to us. “Vietnamese people honor the dead on the first day of Tet, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, by burning paper products. You can burn anything that you want to send to deceased relatives for use in the afterlife.”

We continue down the street, and I see workers working tirelessly on a myriad of goods, all made of paper: dishes, shoes, hats, wardrobes, stereo systems, laptops, counterfeit money, and motorcycles.

As we get back on our bicycles, I look at my mom.

“Silly, huh?” I ask. “I can’t believe people really believe that works.”

“Yes, it doesn’t really make any sense,” she says. Then, she pauses. “But, maybe we should burn some paper golf clubs to send to your dad. You know, in case he wants to play golf.”

As we pedal back toward Hanoi, I think about whether burning paper golf clubs might give my dad a chance to play a round in the afterlife. It seems unlikely. But, I tell myself, maybe it’s just as unlikely as seeing the incarnation of the Golden Turtle God during your first visit to Vietnam.

A Vietnamese Christmas Eve, sort of

Cycling up Vietnam’s Hai Van mountain pass toward an ancient Hindu temple complex.

MAY 18, 2011 — I’m using all the strength I can muster to power my bike through Vietnam’s Annamite Mountains, battling the suffocating fog and hairpin turns of the Hai Van mountain pass. My mom, who up until now has managed to endure the length and demanding terrain of our cycling trip across Vietnam, has retired to our chase car. I can’t blame her. Yellow signs next to the roadway tell me that I’m fighting against a ten percent grade. I feel more like I’m trying to force a bike up the vertical side of a skyscraper.

I’ve put my bike in a high gear, a strategy which has allowed me to pull ahead of the others in our cycling group, at the expense of my quadriceps. As I muscle my bike up steep switchbacks, leaving tire rubber tracks on the asphalt, Bill and Cliff, the most experienced cyclists in our group, are inching up the pass much more slowly, far behind me. They’re both about 25 years older than me, but I’m still feeling smug that I’m ahead of them.

Tourists explore the ancient My Son Temple Complex near Hoi An, Vietnam.

Nevertheless, with every turn of the pedals, I feel my energy supply depleting. About a quarter of the way up the pass, my leg muscles fail. I’m sweating profusely, I’m totally exhausted, and my legs are immobile. As I sit in on my bike, trying to catch my breath and regain strength, Bill and Cliff catch up to me.

“It’s not easy, huh?” Cliff yells out as I wolf down a Vietnamese Twinkie snack cake rip-off that, in any other situation, I would dismiss as disgusting.

“I’m dead,” I mumble back, my mouth full of a Vietnamese substance meant to imitate the Twinkie ingredient that is meant to imitate whipped cream.

Cliff and Bill, both pedaling in their bikes’ lowest gear, seem to be moving uphill in slow motion — but, unlike me, they are moving. At the sluggish pace of the Hoan Kiem turtle, the two middle-aged men pedal by, leaving me on the side of the road.

“Try a lower gear,” Bill yells as he climbs another switchback above me. “You can make it.”

I rest for a few more minutes, then shift my bike into a low gear and begin pedaling again. In the new gear, I’m moving more slowly, but the pedaling is easier. I’m embarrassed to realize that I’ve just learned the lesson of the Tortoise and the Hare firsthand. The specter of the Golden Turtle God strikes again.

Paddle boats representing nearby towns race against each other on the Perfume River near Hue, Vietnam.

Eventually, I reach the souvenir vendors at the top of Hai Van only a few minutes behind Cliff and Bill, who are sipping tea with my mom. They congratulate me. When I tell them that I’ve learned my lesson, they laugh.

“You’ve learned my best cycling trick,” Bill jokes. “We won’t be beating you for long.”

A small hill nearby catches my eye, and I decide to take a quick hike to the top to get a better view of the blue waters of the East Sea (Vietnam’s name for the South China Sea). As I look down across the lush green valley toward the water, a gaggle of Vietnamese college girls on the hill catches sight of me. I brace myself.

For those unfamiliar with the Charisma Man phenomenon (and comic strip), it’s enough to say that even average-looking, blue-eyed white guys are often treated like supermodels by women in Asian countries. So, I’m not surprised when the group of girls eagerly runs over to me to ask me where I’m from. I tell them, intentionally vaguely, that I’m from the United States, but they continue to press me. Knowing what’s about to happen next, I reluctantly reveal that I live in California. Immediately, they’re clapping and cheering, and I watch them melt into a blob of awe in front of my eyes. Apparently, the sex appeal of being a California resident is, for Vietnamese girls, the equivalent of what being a professional football player moonlighting as an astronaut is for American girls. Guessing that I’m headed for a 10-minute photo shoot, I try to divert the girls by suggesting that we take a single group photo. Though they agree to the group photo at first, each then begs me for a photo of just the two of us. As I take photos with each of them, I assume that, somewhere on Facebook, I will be the American boyfriend featured in the profile picture of tens of Vietnamese college girls.

A bicycle sits on the road on Vietnam’s Hai Van Pass.

After managing to escape my Vietnamese fans, I join my mom and the rest of the cycling group for a luxurious six-mile ride straight down Hai Van Pass. The feeling of flying effortlessly downhill at nearly 30 miles per hour with wind in our faces almost makes up for the pain that we endured getting to the top. But, when we reach the bottom of the pass, Cliff manages to hit a patch of gravel and finds himself lying on the road, his body sliding across the asphalt. We’re all nervous, because earlier during the trip, my mom bruised and scraped her arm when she almost wiped out while cycling on a narrow bridge in Hue. Cliff puts on a brave face and a gallon of antibiotic cream, but, along with the large scrapes and bruises on his leg and arm, his grimace tells us that he’s in pain. It occurs to me to help his ego recover by finding the Vietnamese college girls and telling them that Cliff is a combination professional football player and astronaut living in California, but I am unwilling to cycle back up the steep pass.

Tourists explore the My Son Temple Complex near Hoi An, Vietnam.

Instead, Cliff recovers and gets back on his bike. As the six of us continue cycling toward Hoi An through the countryside, hoards of Vietnamese school children on the street yell, “Hello!” and “What’s your name?” Some of them even demand a “high five” as we speed by.

A woman rides a bicycle near a ride paddy near Hoi An, Vietnam.

The next morning, which also happens to be the morning of Christmas Eve, we bike to My Son, a valley filled with 70 partially-ruined Hindu temples and tombs built by Champa Kings, who controlled southern and central Vietnam from the 7th century to 1832. Thankfully, despite his accident, Cliff still seems mobile, even without attention from Vietnamese college girls. As we wander through the My Son temple complex, Teng (our guide) tells us that the United States destroyed many of the temples with carpet bombing during the Vietnam War. Once again, we find ourselves in the uncomfortable position of seeing firsthand the repercussions of a complex war from America’s enemy’s point of view. None of us know exactly what to say to him or how to react.

A “WHY NOT DONUT PANCAKE” sign sits in front of donuts for sale in Hoi An, Vietnam.

After returning to our hotel, Cliff and Bill invite me to join them for a guy’s-afternoon-out in downtown Hoi An. I hope they’re inducting me into their secret Experienced Cyclists Club. I feel like we’re a parody of American tourists as we browse the shops: Cliff visits pharmacies trying to describe Ambien to Vietnamese pharmacists, Bill visits every suit tailor in a five-block radius looking for a golf-shirt pattern that he deems manly enough to wear, and I ignorantly talk with suit tailors about the logistics of buying a custom-tailored Vietnamese suit (which, admittedly, I have decided that I must do at my mom’s insistence). In the end, I’m the only one who ends up making a purchase — the Vietnamese haven’t heard of Ambien and don’t make many manly shirt patterns. After buying sweet treats from a vendor whose nonsensical sign reads “WHY NOT DONUT PANCAKE” (how could I resist?!), we spend the rest of the afternoon enjoying cocktails in a local bar.

A Vietnamese boy dons a Santa Claus suit in a Christmas pageant in Hoi An, Vietnam.

In the evening, our hotel’s management excitedly invites us to the dining room for a Christmas Eve celebration. When we exit the hotel elevator — which is playing a Vietnamese Muzak version of “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus” — into the lobby, we’re greeted by an awkward, mostly female hotel staff wearing Santa Claus hats, doing their best to get into the Christmas spirit. A Vietnamese Christmas-song cover band, complete with two acoustic guitars and a snare drum played like bongos, is playing “Autumn Leaves,” a jazz standard that isn’t remotely Christmasy. As we eat buffet roast beef in front of a city of enormous gingerbread houses, children bussed in from a Vietnamese middle school perform a nativity play and then dance and lip sync to a musical medley of Christmas classics. They do Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree, and Jingle Bell Rock. You haven’t lived until you’ve seen a ten-year-old Vietnamese boy lip sync Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer while wearing a Santa Suit with a Ho Chi Minh-inspired mustache.

Vietnamese children perform in a Christmas pageant in Hoi An, Vietnam.

As I watch, I realize that our Vietnamese hosts think they need to transplant an American Christmas to Vietnam to keep their visitors happy. It’s especially strange, considering that 85 percent of the Vietnamese population is Buddhist and very few celebrate Christmas. Ironically, American Christmas is exactly the thing my mom and I have traveled to Vietnam to try to escape during the first Christmas holiday without my late father. I think about how much he loved Christmas, and chuckle, imagining how much he would have hated the Vietnamese imitation version.

While we’re watching six-year-old Vietnamese girls dressed as angels dance around baby Jesus, a couple of women at a table nearby catch my eye. At first, I assume that they’re Vietnamese, but I notice that they’re also sitting with a guy speaking English, and they look as bewildered by the offbeat Christmas extravaganza as we are. When I introduce myself, they spend the next five minutes mocking the matching, skin-tight bike shirts they saw our group wearing earlier in the day. Then, the three (Helen, Grace, and Lee) tell me that they’re Australians, and they invite me to join them at the pool after the festivities.

After the Christmas pageant ends, next to the hotel pool reflecting the Christmas Eve moon, the Australians teach me how to play a traditional Vietnamese card game called Tien Len (also known as Thirteen). At first, I’m not very good at the card game. Every time I lose, Helen demands that I drink a Saigon Beer. While we play, she tells me that three of them are best friends from Melbourne who decided to take a holiday trip together. We play late into the night, until no one can bear to look at another Saigon Beer. Even despite the imported American kitsch, the night feels like an authentic Vietnamese Christmas Eve.

Did Pizza Hut win the Vietnam War?

Bicycling to the Cu Chi Tunnels and War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

MAY 29, 2011 — After a boat ride across Nha Trang Bay and a tour of coffee and flower plantations in Da Lat, my cycling group lands in Vietnam’s largest city: Ho Chi Minh City (formerly known as Saigon). Considering that we’re in the largest city in a Communist country, we’re surprised to see streets packed with car and motorcycle traffic with a wide selection of upscale retail stores. We see luxury hotel brands like Hyatt and Sheraton, fashion brands like Donna Karan and Calvin Klein, and restaurant chains like Hard Rock Cafe, Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf, KFC, and Pizza Hut. We don’t feel much like we’re swathed by Communism when my mom and I visit the French colonial Majestic Hotel’s rooftop breakfast buffet, which serves a lavish Western-style breakfast. While waiting for the elevator after eating a custom-made omelet, I start talking to two twenty-something American tourists, Lauren and Nicole, who are sneaking plates piled high with food into the elevator.

The “economic miracle” of capitalism has deeply infiltrated Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, where most own a motorized scooter.

“Hungry, girls?” I ask.

“My mom broke her leg, so we’re bringing her breakfast in bed,” Lauren says, winking at me. I can’t tell if she’s winking because she’s pleased to have concocted an outstanding lie designed to make me feel guilty for accusing her or if it’s just that she thinks that I’m cute. I hope that it’s both. In the elevator, Lauren tells me that her mom broke her leg right before their scheduled Christmas trip to Asia, but the three decided to go ahead with the trip anyway. Her food-stealing cover story is, at least, somewhat convincing. Lauren and Nicole say goodbye to me at their floor, and I ride the elevator down to meet my mom and the rest of the cycling group outside. We start cycling toward the Cu Chi Tunnels, an enormous, underground, 75-mile tunnel network used by the Viet Cong during the Vietnam War.

A man demonstrates how Cu Chi Tunnel entrances were camouflaged during the Vietnam War.

After parking our bikes at the Cu Chi Tunnels entrance, we’re ushered into an underground bunker, where Cao, a 60-something man who served with the Viet Cong, starts telling us about his War experience. I’m a little surprised to encounter a Vietnamese man in his sixties, because we’ve seen very few Vietnamese people over 40 years old during our cycling trip. Much of the time, we’ve been surrounded on roads by young children on bikes and teenagers on motorcycles. From Cao’s description of the War, it’s clear why this has been the case: a disturbingly large number of Vietnamese were killed or left the country after the fall of Saigon in 1975. Pointing at a map and diorama, Cao explains how Vietnamese soldiers and families tried to live underground for years in bunkers like the one in which we’re sitting. He says that the bunkers included hospitals, arms stores, water wells, bomb shelters, and kitchens. The underground kitchens had long chimneys, so that smoke would be adequately diffused before reaching the ground, keeping the tunnels hidden. The tunnels also included booby traps made from bamboo spikes and grenade trip wires, which made it more difficult for American “Tunnel Rat” soldiers to infiltrate the tunnels.

A former Vietnamese soldier describes living and fighting underground in the Cu Chi Tunnels.

Cao tells us that tens of thousands of people were killed in the tunnels, and his graphic descriptions of the terror he felt when American forces tried to attack the tunnels by bombing them, filling them with water, or throwing grenades down into them, are as terrifying as similar stories I’ve heard about the War from the American point of view. I’m horrified by the idea of being drowned or crushed underground while baking muffins in a secret, underground kitchen.

A spike trap lies underground at Vietnam’s Cu Chi Tunnels.

Still, Cao boasts of the exceptional resilience of the North Vietnamese, who had very little technology as compared to the American military. As I listen, it’s hard for me to know how to feel, knowing that Viet Cong were killing Americans and South Vietnamese just as Americans were trying to kill tunnel-dwelling Cao.

“But how did you escape being killed?” I ask Cao, expecting him to tell bravado-filled stories of his steadfastness.

“Pure luck,” Cao replies, in Vietnamese. “Tens of thousands of people were killed in the tunnels, and I happened to be one of the few that escaped. The war was horrible for both you and us. No one should have to fight in a war like that.”

After Cao’s presentation, Teng (our guide), brings us to see one of the tiny tunnel openings, where I get a chance to lower myself underground and hide the tunnel entrance with a camouflaged door covered in leaves. Though the tunnel has been widened for tourist use, after being in it for a single second, I start panicking and feel like I can’t breathe. I crawl out as quickly as possible.

A sign advertises the veracity of the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum exhibits.

Next, Teng takes us to a hut where a man is selling rudimentary rubber sandals made from strips of used tires. The sandals look more like refuse from a traffic accident than anything made by Teva.

“When I was a kid during in the 1980s, these were the only shoes we had,” Teng tells us. “We didn’t even have enough rice to eat. We almost never had meat to eat, but when we did, it was a very, very special day.” At first, I’m baffled by this, considering that, today, Vietnam is the world’s second-largest rice exporter. Teng explains that the Communist government didn’t loosen restrictions on commerce and private farming until 1986, but, when it did, what the Vietnamese now call the “economic miracle” resulted.

Next, we visit a “Self Made Weapons Galley,” where we see a myriad of low tech booby traps — the “Clipping Armpit Trap,” the “Folding Chair Trap,” and the “Swinging Up Trap,” all of which are variations on a hole in the ground filled with razor-sharp spikes of death. We end our tour at a shooting range, where tourists try their hand at shooting rifles used in the War at targets. Marksman can choose to shoot either from an American side with an M-16 or from a Viet Cong side, with an AK-47.

Downed American helicopters are displayed in front of the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum.

“I can’t imagine an American Vietnam War veteran visiting this place,” my mom says. I realize that I’m at the world’s most disturbed theme park.

On one hand, the Cu Chi Memorial, with its displays of damaged American tanks and Vietnamese booby traps, feels like the Vietnamese boasting of a War victory. But, underneath some of the self-aggrandizement, I detect a strong undercurrent of relief — relief that no one, North Vietnamese, South Vietnamese, or Americans — have to fight another day.

In the evening, Teng takes us to a theater to see water puppetry, a Vietnamese tradition in which wooden, painted puppets perform traditional Vietnamese folk stories in a waist-deep pool. At first, I’m bewildered by his description of the unusual art form. But, during the show, my mom and I are enthralled by the beauty and humor of the performance, and I find myself wondering how it’s possible that the culture that created the delicate puppets gliding gracefully across water is the same as the one that created the “Clipping Armpit Trap.”

Photographs show birth defects allegedly caused by American use of the defoliant Agent Orange in the Ho Chi Minh City War Remnants Museum.

On our last day in Ho Chi Minh City, we decide to visit the War Remnants Museum, a museum which tells the story of the Vietnam War from a distinctly Vietnamese and propaganda-laced point of view. Exhibits describe the French as American “henchmen,” the South Vietnamese government as the “repressive and murderous U.S.-Ngo Dinh Diem regime,” and the South Vietnamese military as “puppet military forces.” Exhibit summaries charge the U.S. government with setting up concentration camps designed to “keep strict control of the people by trampling on their right to freedom of residence, freedom of movement to earn their living in a normal life.”

A chart boasts of the ineffectual use of bombs used by American forces during the Vietnam War.

We walk through an “Agent Orange in the Vietnam War” exhibit, which shows disturbingly graphic photos of children with birth defects purportedly caused by the use of the defoliant Agent Orange by American forces. We also see a “Tiger Cages” exhibit, which describes violent torture techniques allegedly used by American forces against the North Vietnamese and includes reconstructions of tiny jail cells purportedly used to torture prisoners of war. Even if only half of the museum’s historical claims are true, it’s clear that the Vietnam War was a Hell on Earth for the soldiers on both sides.

As I’m leaving, though, I realize that I’m saddened by the tone of the museum. Because the Vietnam War was so unpopular even in the United States, the museum curators missed a chance to present visitors with more sophisticated depiction of the conflict by illustrating the nightmare that both the Vietnamese and the Americans experienced. Instead, I’m disappointed that it’s so easy for non-Vietnamese visitors to discount exhibits completely because they’re so one-sided.

A five-person Vietnamese family squeezes on to a motorcycle in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

At night, before leaving for Siam Riep, Cambodia, my mom falls asleep early, and I find myself feeling antsy. I take the elevator to the Majestic Hotel’s rooftop bar, where I run into Lauren and Nicole, the two girls I saw taking/stealing food from the breakfast buffet. They’re having drinks with Lauren’s mom, Deborah, who actually is wearing a large leg cast. I feel bad for accusing the two girls of stealing buffet food and offer to teach them all to play Hearts, a card game beloved by my dad that our family played for many years.

On the rooftop of the luxurious Majestic, as I deal cards, the four of us gaze out over Ho Chi Minh City, at skyscrapers filled with American upscale retail stores, luxury hotel chains, and fast food restaurants. I marvel at the thought that this extravagant French colonial hotel was rebuilt after the Communists took control of the country.

Sipping on a cocktail, I begin to wonder whether Ho Chi Minh, lying in a cryogenic freezer in his mausoleum in Hanoi, has any idea that, though American soldiers eventually left Vietnam, his Communist regime didn’t win the War.

I wonder what he would say if he were revived, only to discover that Pizza Hut actually won the War.

How to Take a Cycling Trip through Vietnam and Cambodia

OVERVIEW: Vietnam is a great destination for a cycling adventure, but keep in mind that the Vietnam of 40 years ago is gone: in cities, you’ll be navigating through seas of cars and motorcycles, and in the countryside you’ll be traveling on mostly-paved suburban roads.

LOGISTICS: Though arranging a cycling trip in Vietnam on your own is possible, we booked our trip through bicycle vacation company Ciclismo Classico. The company arranged a cycling guide, bicycles, a chase van, luxury hotel accommodations, meals, and the route for us. Using a company like Ciclismo Classico is a great choice if the idea of planning a cycling trip in Southeast Asia on your own seems too daunting. Joining a group cycling trip greatly simplifies logistics, but, keep in mind, you’ll be traveling with a group of about six strangers. During our trip, we ran into other cyclists who had arranged contiguous bicycling routes through Vietnam without a chase car; plan carefully if you try this — adequate accommodations can’t be found everywhere.

ROUTE: We divided our trip into five legs. First, we started by cycling around Hanoi. Second, we took a flight to Hue and cycled around it, Da Nang, and Hoi An. Third, we took a flight to Nha Trang and cycled around it and Da Lat. Fourth, we flew to Ho Chi Minh City. Finally, we flew to Siam Riep, Cambodia and finished the trip by cycling around Angkor’s ancient temples. View the route below or download the Without Baggage Cycling Vietnam and Cambodia GPS track in GPX or KML format.

Hanoi Cycle Details

Hue Cycle Details

Hue to Hoi An Cycle Details

Hoi An & My Son Cycle Details

Nha Trang Cycle Details

Dalat Cycle Details

Ho Chi Minh City Cycle Details

How to Visit Vietnam’s Cu Chi Tunnels

OVERVIEW: The Cu Chi tunnel network is famous for its strategic importance during the Vietnam War, and a visit there will certainly be one of the highlights of any trip to Vietnam. The Cu Chi area lies 65 kilometers northwest of Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) and the section preserved for tourists is open daily from 7 AM to 5 PM. Admission is 70,000 VND (US $3.50).

LOGISTICS: Any tour company in HCMC will happily arrange a half-day trip to the Cu Chi Tunnels and the nearby Cao Dai Temple. You can also hire a taxi to for the same trip (US $40). It’s possible to bike there, as we did, though our cycling guide company drove us out of HCMC city traffic to a rural road in Tan Phu Trang before we cycled the rest of the way to the Tunnels.

ROUTE: The cycling route we took to the tunnels can be seen on the Without Baggage Cycling Vietnam and Cambodia GPS track in GPX or KML format.

Great piece, Hank. Vietnam is high on my list but you may have just pushed it to the top. Looking forward to part two. Keep on keeping on, as they say, some do, at least.

ho chi min only wanted one country that was free to make its own decisions. he got it. I was amazed by the resolve that the Cu Chi guerrillas displayed and the lengths that they went to become an independent nation. Your view is from a comfortable place that allows you to have a condescending attitude toward people that are just now starting to prosper and find their value. It is a young nation having only known peace for about 30 years (the 5 years after the war weren't peaceful). We left Vietnam like a little league team forfeits a game when the score is beyond reach. When you look at the country as a whole there was only a small political faction in Saigon that did not support Ho Chi Min.

I don't mean to be condescending at all — obviously, this is a very complex issue. The main point is that war is tragic on all sides, and propaganda doesn't leave enough room for that truth. In the end, even though the Communists took control, it wasn't until Vietnam embraced capitalism that the suffering of its people started to ease. This is evidenced by the over 1.5 million people that fled Vietnam after the fall of Saigon (not a small faction).

Fantastic journey Hank! I'm planning a trip myself through Asia. This will hopefully happen in 2015 and I'm going to take a few month time.

Until then I'll keep on reading these blogs. Thanks, Stephen.