AUGUST 27, 2012 — “Cheburashka! Skazhi [say] Cheburashka!” Marina demands, as we drink two shots of Russian vodka together. She is an effervescent Russian medical student, with long blond hair and classic features, who doesn’t speak any English. We’re sitting with our mutual friends Anna, Alena, and Sasha at a Caribbean-themed dance club near Moscow’s Barrikadnaya Metro station, and we’ve already downed three shots of vodka in celebration of Alena’s birthday. Though I’ve only been in Moscow for three days, I’ve already verified that the stereotype of Russians being obstinately dedicated to their vodka is entirely accurate.

Muscovites sit on the edge of a fountain at the All-Russia Exhibition Centre (VVC).

In my quest to live like a true Muscovite and avoid behaving like a predictable tourist, I started my trip avoiding Moscow’s typical tourist haunts, like the Kremlin, the Bolshoi Theatre, and the State Museum. Instead, I contacted Anna — a thoughtful, English-speaking Russian children’s book editor with a round face, short blond hair, and piercing blue eyes — using the backpackers’ mecca Couchsurfing and asked her to let me tag along during her normal weekend activities. Anna, an unapologetic thrill seeker, soon introduced me to her friend Alena — a warmhearted woman with curly, brown hair searching for a publishing job — and the three of us spent the afternoon at the All-Russian Exhibition Center (VVC), people watching and riding vomit-inducing, Western-style carnival attractions. Afterward, when the two asked enthusiastically if I’d like to join the rest of their friends to celebrate Alena’s birthday, I jumped at the opportunity.

A Western-style ferris wheel entertains visitors to the All-Russia Exhibition Centre (VVC).

Though I’ve only known Anna, Alena, and their friends Marina and Sasha for a half day, their genuine personalities make me feel warmly included, as though I’ve known them for much longer. Since I don’t speak any Russian, Marina has spent the night trying to teach me a catalog of profane Russian words, a project which has mostly consisted of her screaming, pizdabol and idi na khuy, the Russian equivalents of “fucking bastard” and “suck my dick,” at me until I dutifully repeat them correctly. But, I can tell that the word she is trying to teach me now, Cheburashka, is something entirely different.

“Chew-burr-ash-kah,” I slowly repeat. “What does it mean?” The group laughs. Anna, who always sensitively comes to my rescue when she detects my cultural confusion, explains: “Cheburashka is a small, bear-like animal, who was found in a crate of oranges and lives in a telephone booth. His friend is a crocodile.” I’m so baffled by this explanation that I assume that either she’s translating a handful of words incorrectly or the cultural divide between me and Russia, in this case, is simply too vast. But, Alena looks sympathetically at the confusion on my face.

“It’s a classic Russian animated kids movie character,” Alena explains. “It’s Marina’s favorite! You can’t really understand it until you see it on VKontakte.” I joined VK, Russia’s Facebook, earlier in the week in an attempt to better integrate myself into Russian culture. Upon signing up, I discovered that, not only is the website better-designed and easier to use than its American counterpart, it provides access to almost every TV show, film, and song ever made, for free, thanks to Russia’s weak intellectual property laws. I make a mental note to see the mysterious Cheburashka before leaving Russia.

Vomit-inducing, Western-style carnival rides entertain visitors to the All-Russia Exhibition Centre (VVC).

The five of us spend the night dancing and drinking until past 3 AM. I note that Moscow is the only place I’ve ever visited that fulfills locals’ promises that it’s a city that never sleeps. When I ask the women about their lack of male friends, Marina immediately launches into a spirited but indecipherable Russian tirade, which Alena succinctly translates for me as: “Russian men are pizdabols [fucking bastards].” So, Anna, Alena and I instead discuss our favorite TV shows and movies, including Glee, House, and The Truman Show. I’m surprised and impressed by their deep knowledge and love for American culture, and I’m so convinced of Anna’s good taste that I persuade her to watch all three seasons of the excellent, prematurely-canceled, teenage detective drama Veronica Mars.

The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour sits near Moscow’s trendy nightlife spot, Red October.

After singing a bewildering (to me) Russian-English-hybrid version of “Happy Birthday,” we all leave the club at around 3:30 AM. I expect that we’ll head back to our respective homes, since the women live in a northern Moscow suburb, and I live in an apartment next to Patriarshiye Pond near the city’s center. But, the group offers to walk with me to my apartment, which I interpret as a friendly and protective gesture toward me, the Russia-ignorant American. As the five of us walk the neighborhood’s streets, packed with never-sleeping Muscovites in upscale cafes and the Patriarshiye Pond park, Marina narrates every step of the way with a barrage of enthusiastic Russian. I ask Alena to translate, but Marina is speaking so fast that the only thing Alena manages to say is: “She’s crazy.” So, as we wander through the neighborhood, I simply watch Marina talk. I can’t understand a word of her animated tour of the neighborhood, but the vitality in her eyes, her energetic body language, and the big smile on her face make me think that she’s very different than most Russians, many of whom seem to scowl constantly, a habit ostensibly left over from Russia’s difficult Soviet period.

Beautiful people enjoy cocktails on the terrace of Strelka at Moscow’s trendy Red October, a former chocolate factory. The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour and Patriarchiy Bridge can be seen in the distance.

Even though I’ve been left out of the Russian-only conversation, I’m still disappointed that Marina’s bubbly Russian tour has come to an end when we finally arrive at my apartment door at 4 AM. Now, I’m expecting the girls to say goodbye, but Alena asks me if we can continue her birthday party in my apartment. I’m exhausted from dancing, my brain is swimming in alcohol, and I’m unsure how I can possibly entertain four Russian women by myself. But, not wanting to reveal that, unlike Muscovites, I’m an Ohioan who rarely drinks Russian vodka and needs regular sleep, I invite them inside.

Quickly, I find myself sitting awkwardly in my Moscow apartment in the middle of the night with four Russians, two of whom don’t speak English. I try turning on the TV to watch the Olympics, but the coverage, of course, is in Russian and follows only the Russian team. As mind wanders, an idea rushes into my head of something to do that doesn’t require any of us to talk to each other — a necessity due to our language barrier.

“Charades!” I announce. “We’ll play charades!” Even Alena and Anna, the English-speakers in the group, have never heard this word. “It’s a game where we act out words and phrases,” I explain.

“Oh, pantomima!” Anna exclaims. Quickly, everyone understands, and I divide the group into teams. The game is a runaway success, and we play for hours, using a Russian-English dictionary to help us produce clue ideas. For much of the game, Marina is my acting partner, and though our language barrier makes it impossible for us to talk to each other, I discover quickly that the two of us are the best charades team in the room. In a particularly funny moment, she manages to successfully portray a blond-girl, Russian-speaking version of Barack Obama. Marina’s energy makes communicating wordlessly with her surprisingly easy.

Muscovites dance at the Tiki Bar dance club in Moscow, Russia.

At 7 AM, with Anna asleep on my bed and most of us out of charades clue ideas, Alena announces that, now that the Moscow Metro has started running again, they had better return home. Yet, after they leave, I realize that Russian charades has prevented me from getting tired. I wonder if I’m already turning into a true Muscovite.

On my laptop, I visit VK and start watching the first episode of Cheburashka (with dubbed English dialog). In the classic Russian animated film’s first scene, I see a small creature, which looks somewhat, but not completely, like a bear, emerge from a crate of oranges. After the zoo rejects him (“The critter is an unknown species!”), he moves into a telephone booth, and lonely Cheburashka sadly fills his time by playing with a spinning top by himself. But, when he sees a posted advertisement — “Young crocodile wants to find friends” — he goes to meet the crocodile, named Gena, who is, adorably, playing chess by himself. The two decide to “build a house for those who don’t have any friends” to help all of the lonely people in the world.

In an episode of the classic Russian animated series, Gena (the crocodile) opens a birthday gift from Cheburashka.

I find Cheburashka utterly charming, of course, but more importantly, it underscores the great importance of loyal friendship in Russian culture. Marina’s dedication to Cheburashka and all of the girls’ exceptional kindness toward me immediately starts making cultural sense. Wanting to see more, I watch another Cheburashka episode, in which Gena plays a garmoshka (a Russian accordion) and sings a quirky, adorable song in celebration of his own birthday:

A magician will come in a blue helicopter and will throw us a show for free. Then, he’ll stay for the party, and when he is departing, he’ll make candy grow on the trees.

What a pity that a birthday comes just once a year.

Yes, at Alena’s party, we substituted charades for a magician in a blue helicopter. Nevertheless, as morning sunlight streams into my Moscow apartment’s windows and I watch Cheburashka present Gena with a birthday gift, I feel the strong, unique bonds of Russian friendship wash over me. I decide that it truly is a pity that Russian birthday parties come just once a year.

A palpable history

Exploring Russia’s past in a famous McDonald’s, the Moscow Metro, and a Cold War bunker.

SEPTEMBER 6, 2012 — “During the Soviet period, people never knew where the next danger would come from,” Olga tells me as we drink beer in Moscow’s Johnnie Green’s (Irish) Pub. “During that time, finding a trustworthy Russian friend was very difficult –but, if you found one, you would be friends for life.”

Earlier in the day, I met Olga’s husband, Pavel — a DJ at a Moscow eclectic-rock radio station and lead singer of the appealing Russian rock band The Super Powers — while eating pirozhkis (egg-filled dough) and drinking mors (a traditional cranberry drink) in one of my favorite Moscow cafes, Lavka Bratyev Karavaevih, near famous Patriarshiye Pond. Pavel introduced himself to me when he saw me reading the classic Russian novel The Master and Margarita, and I told him that I got the idea to stay in an apartment near the Pond because one of the book’s pivotal scenes takes place in the park surrounding it. After talking for a half hour, Pavel generously offered to take me out for the evening for drinks with his friends.

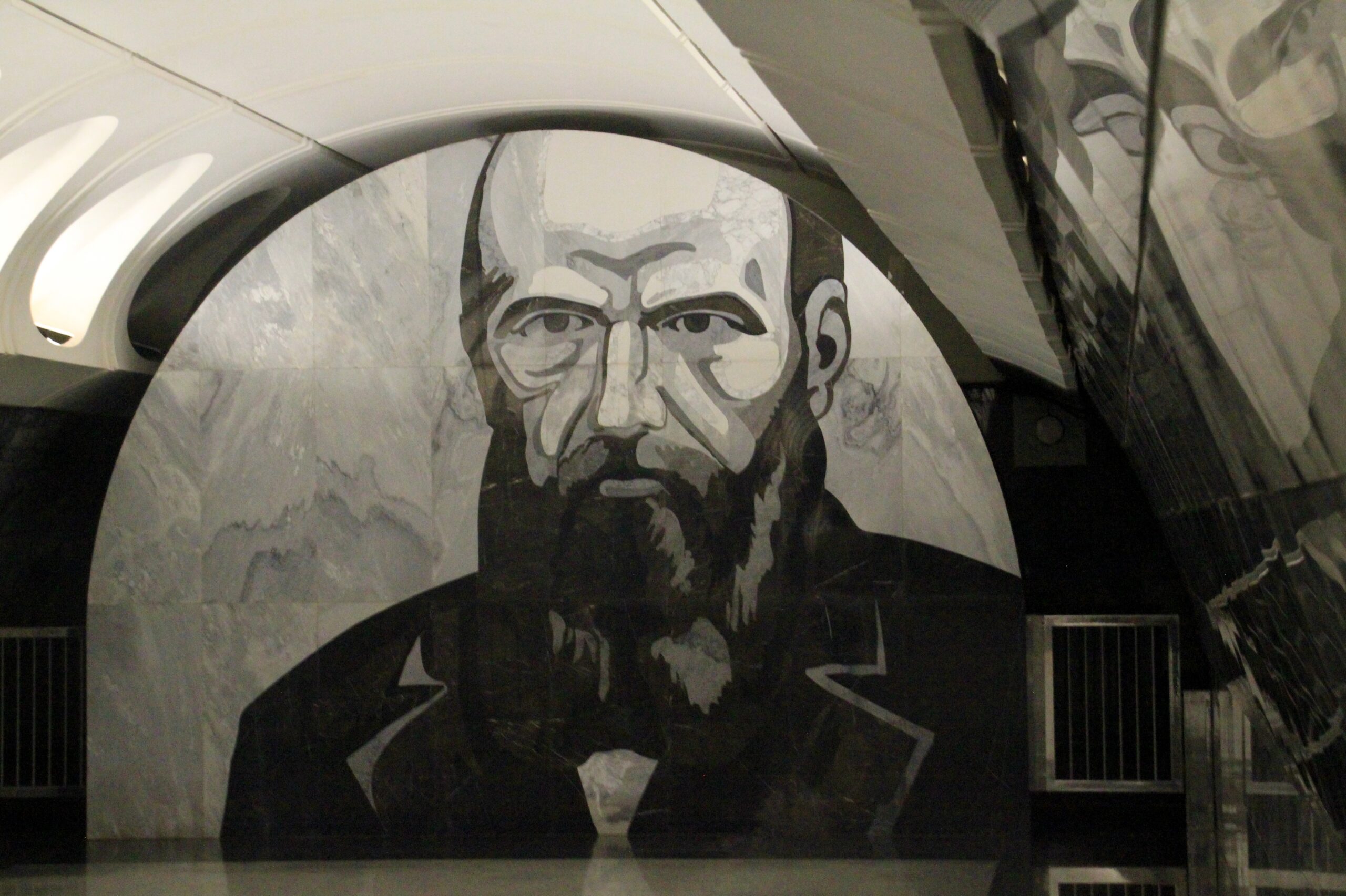

A mural of the head of Russian novelist Dostoyevsky decorates the Moscow Metro’s Dostoyevskaya Station.

“Of course, things have changed now, right?” I ask Olga. “I mean, Pavel started talking to me out of the blue this morning!”

“Yes, people want to meet people now,” Olga says. “They are curious! They feel like they can trust people.”

Olga’s analysis seems accurate. After all, her husband Pavel is just one of many genuinely friendly Russians who have approached during my time in Moscow, curious to meet me. It’s a refreshing change from the fake, sugarcoated, ultracompetitive, aloof attitude worn by many urban-dwelling Americans. It’s also an example of how, while Americans barely seem to remember their past, Russia’s complicated history is always palpable, bubbling below the surface of Russian life.

“Life has been hard for three generations of Russians,” Pavel explains, as he sips his beer. “My grandfather flew in the Russian air force during World War II for America and Russia. My parents raised our family during the Cold War and the grim transition away from Soviet Russia. When I was growing up in the early 1990s, we were all listening to Michael Jackson, but there wasn’t much food to eat. People joined gangs, those people became powerful, and that’s one of the reasons Russia is so corrupt today.” As I listen to Pavel talk about growing up during Russia’s tumultuous post-Soviet transition, I remember the famous photos and videos of 30,000 Russians waiting in a line stretching over a mile in 1990 to visit Moscow’s first McDonald’s in Pushkinskaya Square. I realize that, though my friends in Moscow look much like my friends in the USA, their lives have been very different.

Unique chandeliers in the Moscow Metro’s Mendeleevskaya Station were designed to look like representations of atomic bonds.

The next day, as I walk from my apartment to the Chekhovskaya Metro Station, I pass a McDonald’s restaurant, one which I have ignored at least 15 times before. This time, however, that famous 1990 photo of Russians waiting in line for McDonald’s materializes in my head, and I realize that I’m standing in front of the same historic restaurant. The opening of this McDonald’s, in a country that had been Communist for over 70 years, was a watershed in free market capitalism. I walk inside and, stand, staring curiously at its interior, in a way that I’ve never looked at a McDonald’s before, gaping at hundreds of customers chewing Big Macs and guzzling soda. Deciding to violate my never-eat-at-American-food-chains-abroad rule, I walk up to a cashier.

The Moscow Metro’s Komsomolskaya Station features baroque design, Corinthian columns, arched yellow ceilings, and ornate chandeliers.

“One large French fries, please,” I say. I’m confused when she giggles and disappears, until she returns with the restaurant’s English-speaking manager. It’s a simultaneously entertaining and unsettling experience to order French fries in a McDonald’s and not be understood. With the manager’s help, after I hand over 100 Russian rubles, she gives me the fries. As I walk through the decidedly upscale McDonald’s, past a “McCafe,” with plush armchairs, gourmet coffees, and large case of rich pastries, I notice that my fries taste identical to those in California. Today, Moscow has become a cosmopolitan city, but as I leave the restaurant, I marvel at this McDonald’s, a symbol of Russia’s modernization but also an ever-present reminder of the country’s recent Communist history.

After leaving the restaurant, I descend underground, jumping on to the gray Metro line to make my way toward Mendeleevskaya Station. While I’m walking to transfer to the Metro’s circular, brown line, I notice the station’s unique chandeliers: collections of silver orbs connected together by bright tubes of neon. They’re eye-catching representations of atomic bonds, and I realize that I’m standing in one of the Metro stations that Marina, my Russian medical-student friend, once mentioned to me when we were riding a train together: a station built to honor Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, the creator of the first periodic table of elements. When I had told Marina that I didn’t yet understand Muscovite’s fascination with their transportation system, she gave me a list of Moscow’s most interesting Metro stations to visit.

Bronze statues of Russian citizens stand in the Moscow Metro’s Ploshchad Revolyutsii Station.

So, I decide to ride the Metro without a destination in mind, wandering from station to station to see the art and architecture. As I’m admiring the baroque design, Corinthian columns, arched yellow ceilings, and ornate chandeliers in Komsomolskaya Station, I realize that I’ve been tricked into visiting a museum, something I usually avoid, especially on a trip during where I’m trying to live like a local. Now, though, I’m touring the world’s most functional art and history exhibition, and I realize that a Moscow Metro ticket is the best value of any subway or metro ticket in the world: it’s transportation and an art history lesson in one. I think of the world’s other major subway systems — the dingy and antiquated New York Subway, the super-organized but sterile Tokyo Metro, and the efficient but soulless Shanghai Metro — and decide that Moscow’s system, also known as the Palace for the People, puts them to shame. This, of course, was Joseph Stalin’s intent: in the 1930s, Stalin hoped to overtake the West and build a subway system that could serve as a propaganda tool, illustrating communism’s superiority over capitalism. (Incidentally, he also built a second, mysterious subway system, called Metro-2, used only by government officials for emergency evacuation. No civilians have seen it, but the US Department of Defense agrees that it indeed exists.)

A memorial mural adorns Park Pobedy Station in the Moscow Metro.

I continue wandering from station to station, admiring the mosaic memorializing the 300th anniversary of Russia and Ukraine’s unification in Kiyevskaya, bronze statues of Russian citizens who reaped the benefits of Russia’s 1917 October Revolution in Ploshchad Revolyutsii, the bas-reliefs depicting the history of electricity technology in Elektrozavodskaya, and the large, eerie mural of the head of Russian novelist Dostoevsky in Dostoyevskaya. I visit Lubyanka, one of the two locations of the 2010 Moscow Metro suicide bombings perpetrated by Islamist Chechen terrorists, and I even try to find the ephemeral Art Gallery Train, which, my librarian friend Dasha told me, showcases works of art from the Russian Museum on one side of the train. But, after waiting for the train for an hour and a half without success, I decide that maybe I’d have a better chance of discovering a secret entrance to Metro-2.

I take a train to Taganskaya Station, where I find myself on a residential street searching for a building which, I’ve read, is a false shell hiding the entrance to a Stalin-built underground bunker, left over from the Cold War era. I wander around confused until I hear a group of men walk by me speaking English obnoxiously loudly and realize that they must be Americans on their way to the same bunker, called Bunker 42. I follow them as they walk next to a nondescript, yellow building and through an olive green gate affixed with an enormous Soviet Union red star. At first, I’m still not totally sure that I’m in the right place, but after we descend 18 flights of stairs until we’re trapped 65 meters (213 feet) underground, I feel more sure that I’ve found the right place but less sure that this strange tour is a good idea at all. Quickly, we’re corralled, with a group of about 20 other tourists, by Vladimir, a guide wearing Russian army fatigues and speaking with a strong Russian accent.

Bunker 42 sits below a nondescript, yellow building near the Taganskaya Metro Station in Moscow.

“TOUR START NOW!” Vladimir says. “Follow.” His English grammar is so jumbled and his vocabulary so limited that I suspect he’s intentionally parodying a bad Hollywood Russian military villain. He leads our group — comprised of Chinese tourists, rambunctious University of Michigan students, and some Russians — down tunnels adorned with terrifying, Cold War-era posters illustrating what to do during a nuclear attack, through an enormous steel blast door shield, and into a dingy room with a few scale models of nuclear missiles and two 1960s-era computers sitting next to a world map drawn onto what looks like a piece of glass sitting in front of a blackboard. He extracts two volunteers, a Chinese teenager and a University of Michigan frat boy, from the audience, positions them in chairs in front of the computers, and dims the lights. Suddenly, an ominous music cue begins and a movie screen overhead reveals a radar map showing that nuclear missiles, launched from the USA, are heading toward Russia!

Tourists watch a nuclear war simulation in Moscow’s Bunker 42.

“UNITED STATES ATTACKS US! WE MUST RETALIATE,” Vladimir orders. I can hear nervous laughter and murmuring throughout the room. The Michigan students look uneasy, as though they’re unsure whether the US has actually started a war and fearful that, maybe, the US will send them to a treason trial just for entering Bunker 42. I feel a little like I’ve been shot into a bizarre parallel universe in which I’m a Russian Matthew Broderick in a perverse, Soviet version of Wargames. As I watch, Vladimir tells the two volunteers to simultaneously turn the keys on their launch stations and enter launch codes. Both the Chinese tourist and the American obey. On the movie screen above us, we’re shown a montage of scenes of American life: aerial footage of Manhattan, children in classrooms, and people shopping. We see a missile launching from a Russian silo and then scenes, pulled from Hollywood movies, of America under attack: police officers looking helplessly toward the sky, horrified mobs running through city streets, cars cannoned into the air by fireballs, hundreds of buildings flattened in an instant, and trees disintegrating. Then, the screen shows darkness falling over the American central plains and fades to black, and presumably into a decade-long, American nuclear winter.

The room is silent. No one knows exactly how to react — except Vladimir.

“Follow me to try on gas masks,” he demands. We follow.

Communism may be on the decline, Stalin may be dead, and the Cold War may be over. But, in one way or another, they live on in Moscow.

A mysterious Russian soul

An anthropology student shows me the best animated film of all time — and a glimpse into the Russian mind.

SEPTEMBER 10, 2012 — “Have you heard about the mysterious Russian soul?” Dasha asks. I’m sitting in a traditional Russian restaurant with two of my best friends in Moscow: Dasha, an attractive, young librarian with blond hair and a compassionate heart, and her boyfriend Misha, a smart radio journalist with boyish good looks and a mischievous smile.

“I have heard Russians mention it to me,” I answer. “But I don’t really know what it means.”

“Tell him the story about your friend’s mysterious Russian soul,” Dasha says to Misha. Misha smiles and begins telling a story that starts like a romantic comedy. One of his friends decided, after drinking a bottle of vodka, to surprise his wife by taking a flight to visit her for the weekend in St. Petersburg (750 kilometers from their home in Moscow), where she was on a business trip. Yet, here, Misha’s story takes a turn toward the macabre. Misha’s friend missed his flight, because he was drunk. So, he decided instead to jettison his plan and go to drink more alcohol at a Moscow bar to wash away his frustration. At the bar, he became so drunk that he punched someone in the face, and the bar’s security kicked him out. But, the guy who he punched followed him, proceeding to knock out his teeth and steal his wallet. The next day, he discovered that his bank account had been cleaned out.

A Russian woman sells hats and shoes on a Moscow sidewalk.

“That’s the mysterious Russian soul,” Misha says. He announces this as though his story clearly illustrates something deep about Russia, but I’m left utterly baffled. I don’t know whether to be amused by the part of the story that’s an over-the-top romantic comedy, disturbed that the story suggests that most Russians are alcoholics, or horrified that Russian bank managers are so corrupt that a mugger could clear out a victim’s bank account. Regardless, the story makes me feel a creeping sense of melancholy.

Russians relax on the shore of Moscow’s famous Patriarshiye Pond.

Later, I’m amused to discover a “Russian soul” Wikipedia entry, which says that famous Russian novelist Dostoevsky wrote that “the most basic, most rudimentary spiritual need of the Russian people is the need for suffering, ever-present and unquenchable, everywhere and in everything.” Of course, Dostoevsky died in 1881, in a Russia without luxury department stores, fashionable cafes, public transportation, McDonald’s, and pay-as-you-go cell phones, but, nevertheless, I file his idea of the Russian soul into the back of my mind.

I log on to VK, and when I look at my list of Russian friends, I’m thrilled to discover that I’ve been doing such a good job living like a local in Moscow that I know enough people to fill a party — something I’ve never been able to do before while traveling abroad. Hoping that throwing a party in Moscow might help me better understand the mysterious Russian soul, I invite every Russian I know.

A couple enjoys dusk on the edge of Moscow’s famous Patriarshiye Pond.

On the night of the party, I’m unlocking the door to my apartment, when a gaggle of Russian women spill out of another apartment across the hall.

“It’s my 21st birthday!” one with curly brown hair says to me. She tells me that her name is Vera and introduces me to her friends Vasya, Anastasia, and Maryana. “We’ve rented this apartment tonight for my birthday party!”

After I explain that I’m also planning on throwing a party, Vera invites me to hang out with her friends until my guests arrive. Inside her apartment, I see a large supply of Russian vodka, a fantastic spread of delicious-looking cookies and cakes, and a handful of other women DJing the party with an iPad attached to a projector.

“Where are the guys?!” I ask them, noting a recurring trend of missing Russian men at social events.

“They never come,” Vera says. “Russian men are lazy and irresponsible.” I shake my head, incredulous that any Russian man could have such a mysterious (or lazy) soul that he would pass up a party filled with beautiful, Vodka-swilling, young women.

“Well, I’ve invited some guys to my party,” I tell her. “When they come, I’ll introduce you all.” The girls look at me skeptically, like they know something about the male Russian soul that I don’t.

A Russian couple enjoys an afternoon at the Kolomenskoye royal estate in Moscow.

Maybe, I think, they’re just too familiar with the statistics. I’ve read that women outnumber men in Russia (53.7 to 46.3 percent according to a 2011 census), partly due to premature male deaths owing to alcoholism, driven somewhat by the traumatic and difficult socioeconomic changes that have occurred during the last 20 years in post-Soviet Russia. Twenty percent of Russian male deaths are attributed to alcoholism, Russians drink almost twice the amount of alcohol per year as their American counterparts, and Russia has one of the lowest average life expectancies in a developed country for men (60 years vs. 77 years for other European men). But, I think to myself as Vera pours me a drink, this can’t be the whole story. Every country on Earth has cultural problems with alcohol.

A Russian woman sends a text under a bronze statue of a miner at the Ploshchad Revolyutsii Moscow Metro station.

While I’m sipping my drink, Vasya — a confident, earthy woman with flowing, dirty blond hair and a wise smile, wearing a brown tank top and khaki dress — approaches me, looks me in the eyes, and asks, “Would you like a cookie?” I’ve just eaten dinner and I’m not at all hungry, but refusing a sugary treat from this girl seems like something only an idiot would do.

“Wow,” I say, as I take a bite. I’m genuinely impressed. It’s the best baked treat I’ve eaten during my time in Moscow.

“I baked it and all the desserts myself,” she tells me proudly, pointing to the coffee table covered in mouth-watering pastries. She hands me a pink and blue business card. “I bake muffins, cookies, cakes, and pies, and I deliver too.” This girl, I think, is someone I want to be friends with.

Vasya tells me that her bakery business is a side project — full time, she studies social anthropology at the Russian State University for the Humanities. I smile and tell her that, next to recipes for pies, studying the history of people seems to me to be about the most interesting thing a person can study. She seems genuinely surprised by this and pleased, as though I’m the first person to whom she’s ever been able to reveal her area of study without needing to justify herself.

A mural in the Dostoyevskaya Moscow Metro depicts a scene from Crime and Punishment, in which the lead character Raskolnikov murders two women with an axe.

“Are you a Republican or a Democrat?” she asks. She catches me off guard, but she’s utterly serious, as though it has never occurred to her that this might be a complicated question to ask someone she’s only just met. Barely giving me time to answer, she continues: “Why do Americans dislike socialism? Do you listen to country music?” she asks. Clearly, she sees in me an opportunity to finally get answered all of her questions about America’s complex culture, which is fine with me, since I’m hoping to get from her some insight into the Russian soul.

Though I answer her questions as best I can, I always find myself starting with the preamble: “Remember that America is an exceptionally large and diverse place with no two people alike…” The first time I say this to Vasya, I hate myself for it, because she’s clearly much too intelligent for this disclaimer to be necessary. Nevertheless, I repeat it anyway, because, so often, non-Americans simply fail to grasp the mind-boggling diversity of the United States and the idea that a person from Newport, Rhode Island and another from Newport Beach, California often have almost nothing culturally in common. Thoughtful Vasya, however, understands this intuitively, which doesn’t surprise me, considering that she specializes in anthropology and lives in Russia, a country 1.8 times the size of the United States. We spend a half hour discussing politics and pie, with Vasya treating both topics with the utmost seriousness, until the guests for my party begin to arrive.

An art exhibit at the Vinzavod exhibition shows two Russian generations, dressed identically.

It turns out that the girls across the hall are right: only three of the six Russian guys who I’ve invited to my party show up — and two of them were persuaded to come by their accompanying girlfriends. Nevertheless, I’m happy to see that most everyone else shows up, including Dasha and Misha as well as Alena and Marina from the other Russian birthday party earlier in the week. My party and the one across the hall merge into a mind-bogglingly eclectic Russian-College-Students-and-Random-People-Hank-Has-Met-In-Russia party — which, really, makes it the best kind of party. Having learned a lesson about dealing with varying levels of English proficiency at Alena’s birthday party, I again divide the guests into teams, grab the Russian-English dictionary, and launch another charades game. This time, though, we’ve graduated to Advanced Charades, and each team spends a lot of time devising very difficult clues like “impressionism” and “transient.” My Russian friend Tim, a fledgling film director, proves that he’s the master at stymieing the other team, when he forces my friend Arina to pantomime, stoyak, a Russian word with a double meaning: “water main” or “erect penis.” Her impression of water rushing through pipes combined with her impersonation of a hard-on is undoubtedly the highlight of the party.

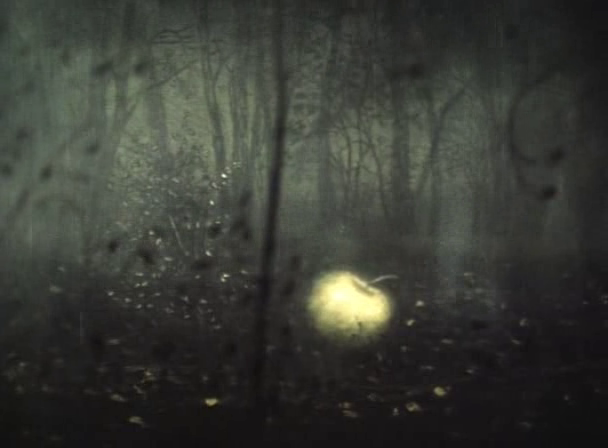

In Tale of Tales, a neon green apple sits in the pouring rain.

Fueled by vodka and wine, our charades game lasts until about 3:00 AM, when it feels a bit like we’ve exhausted the entire Russian-English dictionary. A few of my guests head home, but a handful of us wander into the apartment across the hall, where Vera’s party continues on, unimpeded by the late hour, proving once again that sleep is Muscovites’ lowest priority. The lights are off, but I notice that Vasya is sitting on a couch, playing iPad VJ, projecting whichever VK videos catch her eye onto the dark wall. I grab a piece of one of her cakes and join her.

In Tale of Tales, a wolf admires his reflection in a car’s hub cap.

“Do you think Native American reservations are a good thing?” she begins. I laugh, partly because of her perpetually serious temperament, partly because her version of small talk is, refreshingly, the opposite of small talk, and partly because this question is as difficult for an American to answer as “Does life have inherent meaning?” I try to respond in a detailed, diplomatic way, describing the way the American government repeatedly wronged Native Americans historically but also highlighting the problems that occur when an entire race of people are partially segregated, living under a different set of laws. Nothing I say surprises her, and I chuckle, suspecting that she’s better read on the subject than I am.

In Tale of Tales, couples dance a tango below a street light.

“Have you seen any Russian films?” she asks me.

“I’ve seen some episodes of Cheburashka,” I tell her. “I’ve also seen Tarkovsky’s Solaris, and I once saw Hedgehog in the Fog in an animated film class during college.” Vasya grimaces, seemingly disappointed with my limited knowledge of Russian film history.

“You must see Yuri Norstein’s Tale of Tales,” she says. “It’s considered the best animated film ever made.” When she starts searching VK on her iPad for the film, I realize that she means that I must see it right now — at 4:00 AM, in Moscow, in the middle of a 21-year-old Russian girl’s birthday party.

She reminds me that Norstein, a celebrated Russian film animator, also directed the exquisite Hedgehog in the Fog — possibly the most beautiful animated film that I’ve ever seen — and Heron and the Crane, an elegant, heartbreaking love story. “You must watch,” she says. She taps the play button on the iPad, and the film begins, projected on a large wall in front of the couch that we’re both sitting on.

In Tale of Tales, a boy eats an apple in a snowstorm while standing near two other, enormous apples.

Tale of Tales is not a rollicking, Mickey Mouse-style cartoon created for children, and it’s not the kind of thing someone would watch normally at a birthday party. Instead, the film is like seeing deep into the wondrous dreams, melancholy nightmares, and mysterious soul of a grizzled, Russian man. Vasya and I watch together as the film begins in ethereal sepia, with the sound of a Russian woman singing a quiet lullaby while a baby breastfeeds. Everyone at Vera’s party is a little bit drunk, but, during this screening of Tale of Tales, the room is totally quiet.

In Tale of Tales, a Russian man drinks a bottle of vodka.

I see a neon green apple glowing on the ground in a rain storm. The saddest piano music I’ve ever heard plays as a bull with large horns exercises with a jump rope. An enormous fish floats in the sky.

“The apple symbolizes hope,” Vasya explains. She has turned Vera’s birthday party into a captivating, Russian animated film class.

On screen, a little wolf admires his reflection in a hub cap until he’s left in a fog of exhaust. A glorious cascade of autumn leaves gives way to a beautiful, snow-covered winter. Russian couples dance to the famous tango “Weary Sun.” Soon, the couples are floating in the air and dancing in the sky, until the man in each couple vanishes, one by one.

“This represents the loss of over 10 million Russian men in World War II,” Vasya notes.

I see a boy eating another of the green apples while his father drinks an entire bottle of Russian vodka. The little wolf blows on a piping hot baked potato, trying to make it cool enough to eat. I hear more forlorn piano music and a lonely train whistle.

“It’s a masterpiece,” Vasya whispers. She’s right, of course. The moody film is a lush dreamscape, carpeted with the ambiguous memories of childhood — an ode to nostalgia.

But, as the film ends, instead of looking at the screen, I find myself looking at Vasya. I’m fascinated by how deeply she internalizes the film’s wistful, melancholy mood. I feel like, maybe, the film is giving me a tiny glimpse into her mysterious Russian soul.

Cycling like a Russian

A tireless Muscovite takes me on a marathon Moscow bicycle tour.

SEPTEMBER 29, 2012 — In the last ten years, Moscow’s restaurant scene has exploded, becoming impressively cosmopolitan: Coffee Mania, a popular upscale café franchise, serves moccachinos and eggs benedict with Scottish salmon, Pancho Villa serves surprisingly decent guacamole and enchiladas, and I Love Cake, a California-style brunch cafe that bears more than a little resemblance to the fantastic Huckleberry Bakery & Cafe in Santa Monica, California, even serves Huckleberry’s signature dish, an open egg sandwich slathered in pesto.

Beautiful Novodevichy Convent sits near a bend in the Moscow River in Russia.

I’m sitting in I Love Cake, hoping to get a taste of home by devouring a plateful of French Toast stuffed with cream cheese and a large glass of mint lemonade, when a stylish, athletic Russian woman with wavy brown hair, soft green eyes, and a subtle smile, sits next to me. After she answers some questions I have about the Moscow Metro, she tells me that she’s an insurance adjuster but dislikes the job, and we chat for an hour. I’m impressed by the quality of her English, and I imagine that she’s equally impressed that I’m so accurately conforming to the American stereotype, as I stuff two pieces of bread smothered in egg and cream cheese into my mouth. Between bites, I tell her that I’ve been trying to live like a local while in Moscow, and I haven’t seen many of the typical tourist sites. She smiles, and when she leaves to return to work, we add each other as friends on Facebook and VK using our iPhones.

Bright yellow supports and industrial lights cover Andreyevsky (Andrew’s) Bridge in Moscow.

“I’m a super hero,” Olya writes to me later in the week. “I found a bike for you, so tomorrow we’ll have a little adventure.” She tells me that she likes to forget about her job by going cycling, so, at 7 PM the next evening, I’m following Olya into her apartment, a spacious pad with luxury furnishings and two sparkling Trex mountain bikes sitting near the entrance.

“Wow,” I say, impressed by the modern kitchen’s marble slab countertops.

“My dad was a diplomat and now works on anti-missile technology for the government,” she says. As we walk outside with the bikes, a strange scene of post-Soviet Russia flashes through my head, in which Vladimir Putin presents open-layout kitchens with Viking ovens and Grohe faucets to all of the country’s newly-Capitalist government employees.

“If you get too tired, thirsty, or hungry, let me know,” Olya says, as she mounts her bike. She’s remembering me, the lazy American, stuffing my face with French Toast, I think.

“Hungry? How many weeks will this ride last?” I joke. Olya looks at me, her green eyes twinkling. Then, she starts pedaling toward Andreyevsky Bridge, where we carry our bikes up two flights of stairs to the bridge’s surface. There, we ride, weaving among pedestrians, under the bridge’s bright yellow slats, glass roof, and unusual industrial lights. Once over the bridge, we lug our bikes down more flights of stairs and then begin pedaling along the Moscow River. It’s already clear that Olya’s guerilla-style urban cycling trip is going to be a significantly harder workout than a Los Angeles spin class.

Barbara Bush gave the Make Way for Ducklings art installation to Raisa Gorbachev in 1991 as part of a bilateral arms reduction treaty.

“There’s a great bar and lounge on the top floor of that building,” Olya says, pointing to a tall building with two white columns capped with copper designs. “Oh, it’s also the Russian Academy of the Sciences.”

“I see where your priorities lie,” I say, smiling. As we pedal past monolithic Luzhniki Stadium (the biggest sports stadium in Russia, built by Lenin in 1955 for the Olympic games) and Moscow University — the best university in the city, Olya and I talk about our childhoods and discover that we both loved the Muppets and Sesame Street. She tells me that her favorite character was Oscar the Grouch, and I tell her that mine was Big Bird. The daughter of a Russian diplomat and missile engineer grew up loving the Muppets, I think. While I’m marveling at the startling homogeneity of the world, Olya starts singing the theme song of Bananas in Pyjamas, an Australian children’s show which she also watched growing up but I have never seen.

Street musicians perform in the Square of Europe in Moscow.

We stop at a bend in the Moscow River to takes pictures under a lush elm tree with a picturesque backdrop, reflected in the river, of the bright white and red, castle-like UNESCO World Heritage site Novodevichy Convent, Moscow’s best-known cloister and its second most popular architectural attraction (next to the Kremlin). I’m thrilled to be seeing Moscow’s most compelling sights in an organic way, with a native Muscovite. Nearby, I see an endearing collection of duck statues, depicting the American children’s book Make Way for Ducklings set in the Boston Public Garden. I read on a plaque that the Barbara Bush gave the art installation to Raisa Gorbachev in 1991 as part of a bilateral arms reduction treaty, and I find myself continually surprised by Moscow’s seemingly boundless supply of historical signifiers.

A performer rides a Wild Bike on Arbat Street in Moscow.

“Are you tired yet?” Olya asks. She seems so sure that I’m going to die without a constant supply of French Toast and mint lemonade during the ride that I can only assume that her other Russian friends never manage to match her endurance during her marathon cycling outings.

“Don’t worry; I’ll be fine,” I say, trying to convince her. “Remember, I hike and cycle all the time. You’ll probably get tired before I do.” I regret saying this immediately, knowing that this strong, independent Russian woman will interpret this as challenge.

Olya explodes with speed, shooting over the steel and glass Bogdan Khmelnitskiy Pedestrian Bridge, past the Square of Europe — 48 European flags, celebrating Russian’s integration into European civilization, and a fountain with an abstract, interlaced stainless steel pipe sculpture resembling the head of Zeus and the girl Europa — and across the Moscow River and Borodinsky Bridge, with a view of the Russian White House, the home of the Russian government.

A Stalinist skyscraper sits on a block in Moscow, Russia.

Next, we fly down historic Arbat Street, one of Moscow’s oldest thoroughfares and the first pedestrian-only street in the Soviet Union. Historically, the street served as Moscow’s primary trade route, the place from where Ivan the Terrible’s bodyguards issued orders of mass executions, the route of the French’s march to the Kremlin during Napoleon’s Russian Campaign of 1812, and the home of many high-ranking government officials during the Soviet era. As we pedal, I admire the 18th and 19th century mansions lining the street, in which many members of Russia’s intelligentsia lived, including author Alexander Pushkin, poet Bulat Okudzhava, and novelist Andrey Bely. We cycle past the squat, red and white Arbatskaya station (Moscow’s first Metro station, opened in 1935), gaudy souvenir shops, chain restaurants, painters, and performance artists.

Pedestrians walk over Patriarshy Bridge toward the Red October nightlife hotspot in Moscow.

We’ve been cycling for about two hours when I stop to investigate a crowd of people watching bystanders pay money in return for a ride on a “Wild Bike,” a specially-designed bicycle with handlebars that turn the bike’s front wheel in the opposite direction of the rider’s intention.

“Are you sure you’re okay?” Olya asks when she sees me stop. “You look tired. Are you tired?”

“I promise — I’m not tired,” I say. But, I do want to try the Wild Bike, so I pay a fee to the owner and try to impress the Russian crowd. I’m embarrassed when I fall over on my first attempt — riding a reversed bicycle is unbelievably counterintuitive and difficult — but I do so much better than the other contenders on my second and third attempts that Olya and the crowd applauds, and the bike’s owner refunds my money.

Afterward, when I spot a Pinkberry (frozen yogurt) franchise on Arbat, I’m so amazed to see one that, even though I’m afraid Olya will think that I’m starting to wimp out, I suggest that we stop for a snack. Like so many things in Moscow, the yogurt is ridiculously overpriced (about US $10), but it’s a perfect frozen treat to end our ride as dusk falls.

Tourists look at The Sins Monument in Bolotnaya Ploshchad in Moscow.

“Are you ready to keep going?” Olya asks, after we finish eating. Wanting to make up for my frozen yogurt demands and hide my surprise that she wants to keep riding now that it’s past 9 PM and the sun has begun to set, I simply exclaim, “Yes!” and we carry on.

In the balmy Moscow dusk, we cycle past the stunning Cathedral of Christ the Savior — the tallest Orthodox Christian church in the world, finished in 2000 — which Olya tells me used to be the site of the world’s largest open air swimming pool, where her parents used to go swimming. We cycle over the Moscow River again on Patriarshy Bridge, a steel, pedestrian arch bridge that is arguably the city’s most beautiful, then over famous Luzhkov Bridge, upon which lovers attach padlocks to iron trees to represent their eternal love. It occurs to me that Olya should quit her insurance job and start a bicycle tour company, leading people on romantic, nighttime tours of all of Moscow’s historic bridges.

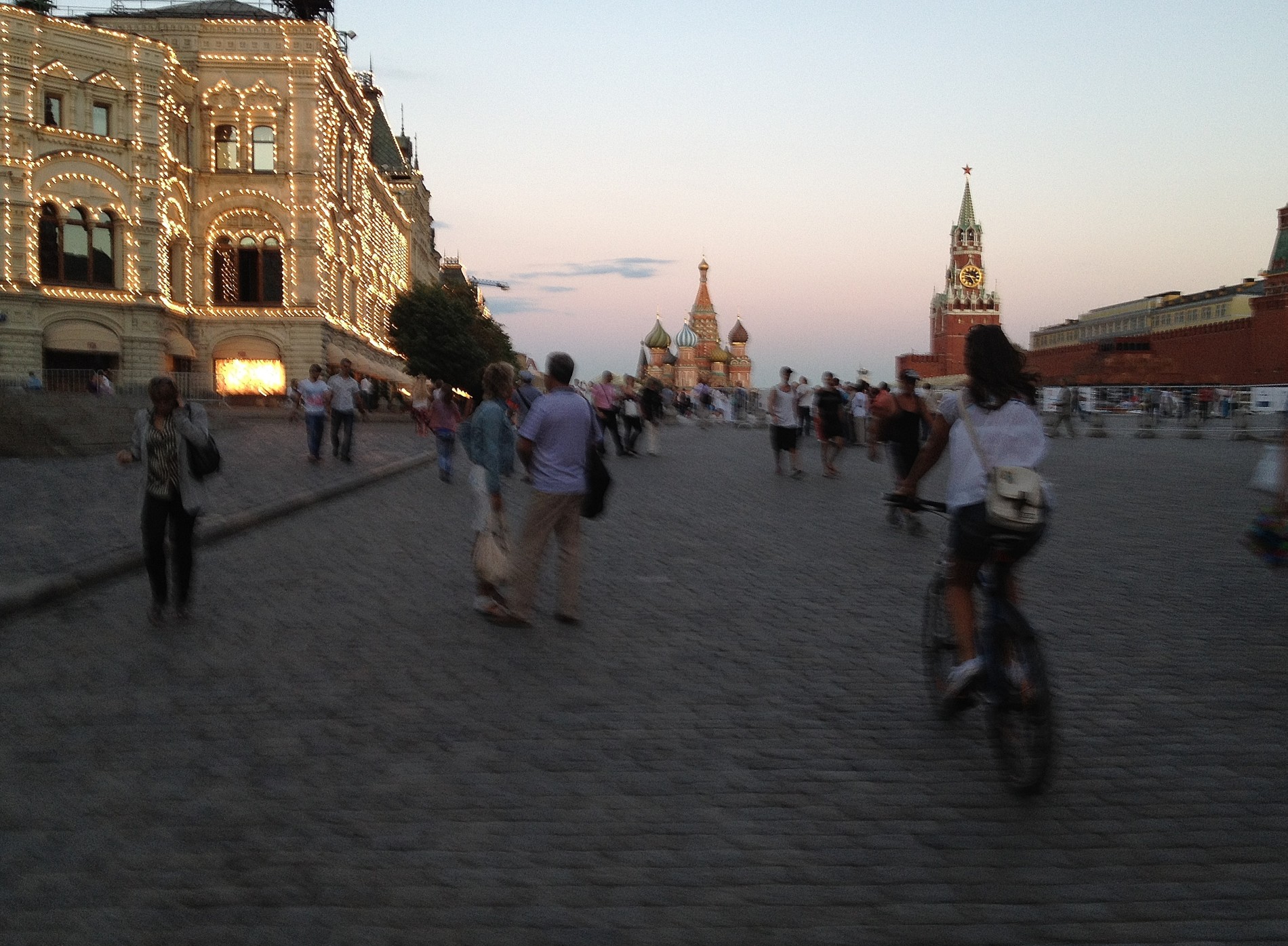

The luxury GUM department store and the State Historical Museum flank Moscow’s Red Square.

“There are many problems with Russian culture,” Olya says when we stop at The Sins Monument, a collection of sculptures representing various sins surrounding two statues of innocent children. After she points out the statues representing alcohol abuse, drug abuse, ignorance, indifference, sadism, poverty, prostitution, and thievery, she tells me a story about a day in Moscow when a thief grabbed her cell phone from her hand as she was using it, and many watching bystanders did nothing to help her. “This would not happen in America, would it?” she asks. I realize, sadly, that I don’t know the answer, but I assure her that Russia does not have a monopoly on citizen apathy.

In the last remaining twilight, we sail through Alexander Gardens, along the red, brick Kremlin wall, and then through stunning Red Square. Strings of white lights glitter on the Russian-medieval, glass-roofed GUM department store, and the vibrant onion domes and spires of iconic St. Basil’s Cathedral tower beyond.

By the time we’ve cycled past the Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building (one of seven Stalinist skycrapers built in the 1940s and 1950s) and over Novopassky Bridge, I’m very hungry and fairly tired.

“Maybe we should eat dinner,” I suggest. Olya smiles, knowing that Russia just beat the USA in our endurance cycling competition. But, instead of gloating, she leads me to trendy restaurant-club-bar Club Discovery.

Olya rides her bicycle through Moscow’s Red Square at twilight.

It’s past 11:30 PM when we finish dinner, but, to my surprise, Olya doesn’t mention anything about returning home. We continue cycling to the famous, 100-foot, Peter the Great statue near the former Red October chocolate factory.

“There’s a bunch of good bars and clubs in Red October,” she says. Then, remembering her role as Moscow history guide, she adds quickly that the Peter the Great statue is unanimously despised by all Muscovites, presumably because Peter the Great moved the capital of Russia from Moscow to St. Petersburg in 1712 (it later reverted). I admit to her that I love this statue, partly because it’s so ridiculously monstrous and partly because I adore Russian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli’s style. She’s appalled.

A woman prepares to throw a Frisbee while people watch from chair swings in Moscow’s recently renovated Gorky Park.

My legs feel like jelly as we cycle at midnight through the eerie Muzeon Park of Arts (also known as Fallen Monument Park), an open-air sculpture museum containing a horde of sculptures, including many Communist statues that were removed from their pedestals upon the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. In the darkness, we weave between moonlit statues of Stalin, Lenin, Dzerzhinsky, dancing muses, and Greek gods.

It’s almost 1 AM when we finally make it to the recently, brilliantly renovated Gorky Park (Moscow’s version of New York’s Central Park), which has become a bona fide cultural and summer phenomenon. We pass sand volleyball courts, a paddleboat pond, chair swings, chaise lounges, and an outdoor movie theater. When we stumble upon a lawn covered with enormous beanbag sofas, I convince Olya to take another break, and we collapse together on a bean bag, gazing up at the black, starry sky.

“Sometimes, I think that if I don’t stop riding, tomorrow morning will never come,” Olya says wistfully. I glance at her green eyes, transfixed by the Moscow sky. My exhaustion melts away.

“Let’s keep going then,” I say. She smiles. At 2 AM, we get back on our bikes and continue pedaling into the Moscow night.

Prancing on rooftops

In St. Petersburg, Russia, every night can be New Year’s Eve.

OCTOBER 13, 2012 — “Okay, I know this is hard for an American, but we must be very quiet,” Seva whispers as we enter the building’s courtyard next to the Fontanka River in St. Petersburg, Russia. “We’re not allowed to do this. It’s illegal.”

Seva — an 18-year-old, iPod- wearing, St. Petersburg tour guide with wild, curly blond hair, a youthful wit, and a subversive edge — quietly leads me and my newfound friend Nastya into an 18th-century, yellow apartment building with a grid of rectangular windows, up five flights of stairs, through a dark attic with a coarse, concrete floor, and across a wooden walkway. Nastya — an ambitious, smart, fashionable, 23-year-old Russian woman working in advertising with a round face and dirty blond hair — has generously agreed to show me around St. Petersburg after our mutual friend, Alina, had to travel out of town for work.

Seva and Nastya look at the view from a roof in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Nastya and I follow Seva toward a blinding light shining through an opening in the slanted roof until we’re climbing a rickety, wooden staircase. Suddenly, we’re standing on the building’s tin roof, looking down at tourist boats cruising under green, arched bridges crossing the murky waters of the Fontanka, flanked by the white, yellow, beige, and red waffle-like fronts of 18th-century buildings. In the distance, I see St. Petersburg’s most well-known landmarks: the golden dome of St. Isaac’s Cathedral and the green, blue, and grey onion domes of the Church of Our Savior on Spilled Blood.

Tour guide Seva describes the view from a rooftop in St. Petersburg, Russia.

“Try to step only on the ridges,” Seva advises as the three of us walk across the roof and then step onto the roof of an adjacent building. “You don’t want to fall through.” Immediately, I imagine myself unexpectedly crashing through the ceiling of a Russian family’s living room and onto their couch while they’re watching the Russian team compete in the Summer Olympics.

When I ask Seva if giving rooftop tours is his fulltime job, he tells me that he’s simply giving tours for the summer until he leaves to join the Russian army.

“The army?!” I ask, surprised. “But aren’t you too rebellious and fun for the army?”

“Russians can be conscripted for one year when we’re between 18 and 27 years old,” Seva explains.

“If he didn’t do well on his standardized tests to get into university and he doesn’t have the money to bribe someone important, he may have no choice,” Nastya whispers to me when Seva is out of earshot. “But the Russian army can be horrible.” I think of the estimated 40,000 Russian soldiers killed in the Second Chechen War during the last decade, and a haunting image of the disappearing men in Yuri Norstein’s Russian animated film Tale of Tales drifts through my mind. Looking at Seva, a talented and creative entrepreneur, I feel sad.

Nastya stands on a roof in St. Petersburg, Russia.

“I expect they’ll promote me to General immediately,” Seva jokes.

I see Nastya, prancing barefoot in a leather jacket and designer jeans from rooftop to rooftop, her blond hair tousled by the wind and her aviator-style sunglasses sliding down her nose. Near her, on two buttresses emerging from the silver roof next to two rusty satellite dishes, I see a spray-painted mural of the silhouette of a loving mother, holding an infant above her head, masking neon-green light seeping through horizontal blinds. I see that the graffiti artist has tagged his work with his signature. Ahead of me, Seva and Nastya climb together onto a raised section of the roof, teetering on the unguarded edge of a final plummet.

A mural seen on a roof in St. Petersburg, Russia depicts a woman holding an infant.

“They’d never let you do this in America,” Seva says. “In America, we’d be wearing seatbelts and helmets!”

He’s right, of course, but America’s idiosyncrasies are far from my mind. I’m entranced by the experience: the primal graffiti image, the satellite dishes, Seva’s iPod, Nastya’s fashionable clothes, and the fact that, 20 years after the fall of Soviet Russia, an American, a Russian conscript, and a Russian advertising executive are dancing across rooftops above a 300-year-old Russian city. In a single snapshot, the scene seems to tell the entire story of Russia’s complex recent history.

Nastya chats on a phone on Anichkov Bridge in St. Petersburg, Russia.

“Tonight, Father Christmas will come to deliver gifts from Lapland, Finland, where he lives. He’ll bring Snow Girl,” Olga says, as though this is a perfectly normal thing to say.

It’s not New Year’s Eve, and yet, my friend Olga — a graceful, always-smiling, red-haired, music act booking agent — and I are sitting with her friends Emil and Marina in the St. Petersburg dance club Purga, waiting for the New Year’s Eve countdown to midnight. Purga is a special, two-sided dance club; on one side, the club celebrates a fake Russian wedding, and, on the other side, the club celebrates New Year’s Eve — every night of the year.

“Uh, what?!” I say, utterly confused. “First, Santa lives at the North Pole — not in Finland. Second, who is Snow Girl?!”

“He definitely lives in Finland,” Olga, normally the most easy-going person I know in Russia, sternly insists. “And you don’t know Snow Girl?! We call her Snegurochka, and she is the granddaughter of Ded Moroz, who is Father Christmas.”

Russian sculptor Baron Peter Klodt von Jurgensburg’s horse-tamer statues appear throughout St. Petersburg.

“Ok, and she lives with him in Finland?” I ask. “What does she do? Does she help deliver gifts, or what?” It occurs to me that demanding to know the specific job requirements of a fairy tale character — as though it’s essential to root-out corporate inefficiencies in Fairy Tale World and lay off characters nonessential to the bottom line — is offensively American.

“I don’t think she really does anything,” she explains, bewildered. As if on cue, one of the club’s cocktail waitresses, dressed as a particularly sexy Snow Girl in a white miniskirt and white stockings covered in blue snowflakes, gives us all white rabbit ears to wear on our heads. In a flash, she forces Marina into a Christmas tree costume and arranges us all in a circle around her. Immediately, everyone in the dance club begins singing in unison, and it becomes clear that I am the only person in Russia that doesn’t know the lyrics to “The Forest Raised a Christmas Tree,” a traditional Russian folk song. I attempt to lip sync, but I’m not convincing.

St. Isaac’s Cathedral is one of St. Petersburg’s most well-known landmarks.

After the song, as we drink cocktails, Emil tells me that he moved from Baku, Azerbaijan to Russia for his job at a construction company, and Marina tells me that she trains American Bulldogs for Russian dog shows. My brain already feels like it’s about to explode from the incongruousness of it all, when a shirtless man wearing a fake, long, white beard, red nose, and black-rimmed glasses appears and demands that each woman in the bar sit on his lap. I realize that it’s a perverted Father Christmas.

A Russian man fishes in a St. Petersburg river.

“He doesn’t normally look like this, of course,” Olga says. “Usually, every father dresses in a more traditional Father Christmas costume to fool the children.”

“The way he looks is the least of my confusion,” I confess. “In America, he visits on Christmas Eve instead of New Year’s Eve, and the children never see him. He pilots a flying sleigh powered by reindeer, which land and prance across your roof. Then, he enters through your chimney, eats cookies, and leaves gifts under the Christmas tree — all in secret.” As soon as I finish my explanation, I realize that I sound insane.

When a television screen above us begins showing a speech from Russian president Vladimir Putin, the crowd starts yelling.

“Desyat! Devyat! Vosem! Sem! Shest! Pyat! Chetyre! ” the crowd chants, led by Father Christmas’s sexy granddaughter. They’re counting down to the fake New Year, and Olga tells me that the Russian president always gives a televised speech minutes before the real New Year’s countdown.

“ Tri! Dva! Ahdeen! S Novym Godom!” the crowd screams as though they have no idea that it’s not the real New Year.

“I’m so happy that I’ve gotten to celebrate the New Year with my Russian friends,” I say to Olga, Emil, and Marina, as we light sparklers in celebration. Feeling sentimental, I make a New Year’s resolution to continue my Russian friendships long after leaving Russia. Always-gracious Olga smiles.

Snow Girl and Father Christmas visit patrons to dance club Purga during a fake New Year’s Eve in St. Petersburg, Russia.

“Our country may have corruption problems, but you can’t buy friendship in Russia,” Olga says. “Especially in Russia.”

Then, just as though we were celebrating a real New Year, a familiar feeling of melancholy nostalgia and regret overcomes me. Likely because of the intense nature of Russian friendship, I feel, more than usual, acutely aware of the ephemeral nature of travel-born friendships and New Year’s resolutions, real or fake.

Yet, I find myself wanting to capture our mutual feeling of friendship in this fleeting New Year’s moment and stretch it, like a rubber band, along the train tracks back to Moscow, across the 6,000-mile flight path back to Los Angeles, and over the months beyond my trip’s end.

Becoming Russian

Eating shashlik and being boiled alive in a bathhouse at a Russian dacha.

NOVEMBER 29, 2012 — “These are old amusement rides from our childhood,” Misha says. “It was a different country then.” My Russian-librarian friend Dasha, her radio-journalist boyfriend Misha, her childhood friend Mikhail, and I are standing in humid August weather in the Central Park of Vladimir, one of Russia’s medieval capitals. The Russians are staring wistfully at the rides from a Soviet-era, derelict amusement park: a nonfunctioning roller coaster, a rundown carousel, and an abandoned, nautical-themed swing set.

A Russian man paints the Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin on the Nerl River near Vladimir, Russia.

“The 1990s were hard,” Misha continues. “People had no money and every day was like a war.”

“Sometimes, I couldn’t afford lunch at school,” Dasha adds.

While photographing the attractions, I marvel at Russians’ infinite proclivity toward turning any moment into one of introspection. There’s something cinematic about it.

It’s my last weekend in Russia for the summer, and my Russian friends have generously offered to bring me to a dacha, a country vacation house in the environs of a Russian city. I’ve been trying to live like a local while in Russia, and this excursion seems like a perfect, authentically Russian conclusion to my trip.

“How do you like our Russian roads?” Dasha asks me as Mikhail drives us through the Russian countryside. I tell her that the roads themselves aren’t much worse than California’s (potholes abound due to the state’s inept government), but I do notice Russian drivers weaving dangerously through traffic without much regard for safety. “Many Russians have not taken driver’s tests; people just bribe officials to get a license,” Misha explains.

Abandoned Soviet-era amusement rides sit in the Central Park of Vladimir, Russia.

On our way, we decide to visit Vladimir’s UNESCO World Heritage sites: the city’s ancient, bright, white Golden Gate; the five-domed Cathedral of the Assumption with 40-foot high, 15th-century murals, the four-pillared Cathedral of Saint Demetrius; and the picturesque Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin on the Nerl River. We spend over an hour at the Church on the River, wandering its grounds. I’ve been sitting for 30 minutes by myself on the grassy river bank — watching a Russian painter creating an oil-painting rendition of the beautiful, black-domed, blindingly-white church — when Dasha, Misha, and Mikhail join me.

The Golden Gate in Vladimir, Russia is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“To the dacha!” Mikhail urges. “We should relax, bent over.”

“Bent over?” I ask. I often find it nearly impossible to translate Russian humor without help.

“Visiting a dacha is a working vacation,” Mikhail explains, his eyes twinkling. “You are always bent over.” When we finally arrive at his family’s dacha, I realize that he’s not kidding: Mikhail quickly asks me to prepare firewood with an axe, to provide fuel for my virginal experience in a banya, a traditional Russian bathhouse whose interior temperature exceeds 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

I’ve never chopped firewood with an axe before, so I nonchalantly grab an axe and try to look like a manly Russian. But, when Mikhail and Misha stop by to check up on my progress, they see me waving the axe around haphazardly, repeatedly failing to make contact with the wood.

The Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir, Russia is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“You must align the axe, and then let it drop,” Mikhail asserts. “Otherwise, you will axe your leg.”

“There is an old Russian joke,” Misha says. “Here, let me throw you the axe! Why are you keeping silent? Oh, you caught it.” Russians are nothing if not blunt. I heed their warnings.

After I manage to finish cutting the wood (without cutting off my leg, I’d like to boast), Mikhail readies the banya‘s furnace while Misha lights the coals in an outdoor grill and asks me to prepare skewers of marinated meat for shashlik, a Russian style of barbecue. Being American, I regret having missed the class, obviously attended by all Russian boys, that teaches how one becomes a real Russian man. I suspect the class is taught by Vladimir Putin himself.

Flowers bloom in front a dacha, a typical Russian country home.

Nevertheless, I manage to thread the meat onto skewers and help arrange them on the grill, and soon, the four of us are enjoying an excellent Russian meal of syrniki (Russian cottage cheese pancakes), borscht, shashlik, and, of course, vodka.

“Thank you so much for the Russian meal,” I say to my Russian friends as I put garlic on my bread. “The shashlik is great!”

“There is an old Russian joke,” Misha says. “It is a law in Russia: first butter, then garlic. If not, prison.”

“Russian banya is heating to 100 degrees [Celsius] right now!” Mikhail announces with glee, as though he can’t wait to boil the visiting American alive.

After drinking tea and eating pryaniki (traditional Russian ginger cookies) the four of us proceed into the entrance vestibule of the banya. I’m nervous — I don’t visit saunas or steam rooms even in the USA, because I find them too suffocating. In the vestibule, the Russians each grab a felt hat with a Russian Army red star sewn onto it. I feel like an American traitor when I grab one too.

Russian shashlik cooks on a grill outside a dacha.

“Okay, now we take off our clothes,” Mikhail says as he strips down to his underwear. Will they be able to catch me if I ran as fast as I can back toward Moscow? I wonder to myself.

“There is an old Russian joke,” Misha says. “I’m going to banya. If I don’t return, tell the government I was a Communist.”

I look at the two of them dubiously. I can’t imagine what would motivate someone to voluntarily enter a room at a temperature of over 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

“You must experience Russian banya,” Mikhail insists. He’s right, I think. I must experience Russian banya. I don’t want to leave Russia without having tried Russian banya. And when did I start dropping indefinite articles from my English?! Russian banya is already making me crazy.

A Russian feast with shashlik waits to be eaten.

“Okay, let’s do it,” I say, pretty sure that this is something I don’t want to do.

I’m the first to open the door, and we slowly step into the banya.

OH. MY. GOD. HUMANS CANNOT BE THIS HOT WITHOUT INSTANTLY DYING, I think. I begin to panic: My head is GOING TO EXPLODE. TOO HOT. TOO HOT. TOO HOT. No, really, my head is going to explode. SERIOUSLY, I FEEL MY HEAD IN THE ACTUAL PROCESS OF ACTUALLY EXPLODING.

“Lie down,” Mikhail orders. I moan quietly but obey. The four of us lie on the banya‘s benches for about ten minutes. At first, I’m almost certain that my whole body is about to catch on fire, but as I relax, I find myself starting to become more accustomed to the extreme temperature. But maybe it’s a trick; it’s like I’m a lobster and by the time I realize that I’m being boiled alive, it will be too late, I think.

Borscht is a traditional Ukrainian soup.

“In winter, we’d run out of the banya, jump into the snow to cool off, and then run back into the banya,” Mikhail says. I’m hoping that he’s noticed that my head is clearly about to explode. “But there’s no snow today.” So, he leads us back into the vestibule to cool down for about five minutes, and, then, he leads us back into the bathhouse. I’ve just begun getting accustomed to the heat again while reclining on the lower bench when Mikhail grabs a large birch tree branch from a bucket of hot water and starts whipping my back with it.

Syrniki, Russian cottage cheese pancakes, are a traditional Russian dish.

“Wait, seriously, WHAT are we doing now!?” I ask, a bit more forcefully than I mean to. The room is so humid that I feel like I’m breathing hot water.

“It is tradition,” Mikhail says as flagellates me with the branch. “It helps removes toxins.” Though I’m already acquainted with the mysterious Russian soul, I’m still surprised to discover that Russians’ tendency toward masochism goes well beyond my wildest imagination.

“Oh my God, seriously, I’m too hot,” I blurt out. “Too. Hot.” Mikhail, Misha, and Dasha laugh. We step outside into the vestibule again, and I take a deep breath of cooler air.

“There is an old Russian joke,” Misha says. “A Russian finds an American diary which reads: ‘Yesterday, I drank with Russians. I nearly died. Today, I went to Russian banya. It would have been better if I had died yesterday.'”

A Russian banya, or bath house, is made of wood and contains a furnace that can heat the interior to over 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

“But, we must go back inside,” Mikhail says, as the three Russians look at me uncertainly. “We should always visit banya at least three times.” But, they look a little worried. I think that they think that they may have tortured the American too much.

As steam rises off my skin while standing in the vestibule, my mind wanders to Cheburashka, the classic, Russian, animated children’s film that I watched when I first arrived in Russia. I think of Cheburashka’s frenemy, an old woman named Shapoklyak who antagonizes him endlessly. In one of many stories, the old woman steals Cheburashka’s wallet, train tickets, and his crocodile-friend Gena’s garmoshka (a Russian accordion) during a train ride. When the conductor throws Cheburashka and Gena off the train, the two manage to continue their trip by hitching a ride on top of the train’s blue caboose. When the old woman appears again, she has the gall, not only to join them on top of the train, but also to demand that Gena entertain her with a song on his garmoshka. Gena proceeds to play the beautiful, melancholy Russian ballad “Blue Wagon“:

Felt hats in a Russian banya protect bathers heads from the excessive heat.

As all of the minutes gradually fly away, Don’t expect to see them again. We feel sad that our past is gone, But all the best is certainly ahead!

…Our blue train is steaming and swaying, The express train is speeding up! Why does this day have to come to an end? I wish it could last a whole year.

Spreading like a tablecloth, time continues on, And it reaches toward heaven’s horizon. Everyone should believe and hope for the best, As our blue train steams ahead.

Inside a Russian banya, wooden benches wait for bathers.

Before, I had never understood before why Cheburashka and Gena didn’t beat the meddling Shapoklyak to a pulp and throw her off the speeding train. But, as I cool down in my underwear with my Russian friends, it occurs to me that the old woman is intended as a metaphor for life in Russia. She makes life difficult for Cheburashka and Gena, but this adversity continually strengthens their valuable friendship. They can’t help but love each other, and, in turn, the old woman.

As I look at my friends, I feel the final minutes of my last night in Russia flying past, and I wish desperately that there were something I could do to slow the speeding blue train. I brace myself to be boiled alive.

“Let’s go inside one more time,” I say. “I think I’m a real Russian now.”

How to Experience the Nightlife in Moscow, Russia

OVERVIEW: Fly to one of Moscow’s three international airports. From any of the airports, take the AeroExpress train and transfer to the Moscow Metro. From there, it’s easy and inexpensive to travel to most locatons in Moscow.

RED OCTOBER: Take the Metro to Kropotkinskaya station to visit Red October (Krasnye Oktybr), a chocolate factory that sweetened Moscow’s air from 1913 to 2007, recently has been converted into one of the city’s hippest nightlife destinations. Check out Gipsy Bar, considered by many (or, at least, those good-looking enough to get past Russian “face control”) to be Moscow’s best dance club, complete with an outdoor terrace filled by chaise lounges, ping pong tables, and a photo booth. Also, be sure to visit Strelka‘s sumptuous outdoor patio for dinner or dessert. The food at Art Academy is also good.

SO-HO ROOMS: Ride the Metro to Sportivnaya station to see So-Ho Rooms, one of Moscow’s most popular dance clubs. Again, “face control” can be difficult, but if you wear fashionable, elegant clothes (no sneakers and no ripped jeans; jacket and shirt), you increase your chances of being admitted.

TIKI BAR: For a less elitist Moscow night club experience, go to Barrikadnaya station to check out the Caribbean-themed club we visited for Alena’s birthday: Tiki Bar. Professional dancers lead salsa and merengue dance routines for those looking to get their Latin groove on, and the kitchen and bar serve decent food of all kinds and drinks ranging from Caribbean cocktails to Russian vodka.

How to See Russia’s First McDonald’s, the Moscow Metro, and Bunker 42

RUSSIA’S FIRST MCDONALD’S: In Moscow, take the Metro to Tverskaya, Pushkinskaya, or Chekhovskaya station. Russia’s first McDonald’s is located close to the Tverskaya Metro station entrance on Bol’shaya Bronnaya street.

THE MOSCOW METRO: The Moscow Metro has 186 stations and is the third most-used subway system in the world (after Tokyo’s and Seoul’s). Rides cost only 28 Rubles/87 US cents. Most of the stations are worth visiting, but start by seeing some of the most beautiful stations on the circular brown line: Novoslobodskaya (stained glass) and Mendeleevskaya (atomic bond chandeliers and Mendeleev mural), Prospekt Mira (white marble pylons), Komsomolskaya (baroque architecture, octagonal dome, Corinthian columns, and ornate chandeliers), and Kiyevskaya (baroque style, Russia/Ukraine unification memorial mosaic, and Ukranian ceiling frescoes). On the blue line, check out: Arbatskaya (vaulted ceilings and floral reliefs), Ploshchad Revolyutsii (bronze statues of Russian citizens who reaped the benefits of Russia’s 1917 October Revolution), and Elektrozavodskaya (bas-reliefs depicting the history of electricity). Others worth visiting: Dostoyevskaya (large, eerie mural of Dostoevsky ‘s head), Trubnaya (illuminated stained glass mosaics by Russian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli), and Park Pobedy (red marble floors and Tsereteli enamel panels).

BUNKER 42: A false building shell hides the entrance to Bunker 42, a Stalin-built underground bunker, left over from the Cold War era. To get there, take the Moscow Metro to Taganskaya Station. Then, walk north on Gonchamaya (ГончамаÑ) and turn left on Pyatyy Kotel’nicheskiy, a small residential street. On your left, you’ll see a large, yellow building with the address 34 Gonchamaya (ГончамаÑ). Bunker 42 tours run from 10:30 AM to 6:30 PM on weekdays and 11:00 AM to 1:00 PM on weekends. However, call (+7 (495) 500-05-54) in advance to arrange your tour, because open hours and tour times seem unpredictable. The basic “Declassified” guided group tour costs 1300 RUB/US $40 for non-Russian adults and 700 Rubles/US $22 for Russians. Longer, more expensive, more in-depth tours are also available.

How to See Yuri Norstein’s Animated Films

TALE OF TALES: Russian animator Yuri Norstein’s Tale of Tales is considered the best animated film of all time. The moody film is a lush dreamscape, carpeted with the ambiguous memories of childhood — an ode to nostalgia. The entire film can be seen on YouTube: Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV.

HEDGEHOG IN THE FOG is a heartwarming story about friendship with stunning visual effects.

THE HERON AND THE CRANE is a melancholy love story.

THE OVERCOAT is a new animated film on which Norstein has been working for the last 27 years. Read more about it and watch a short documentary about it (in Russian).

How to Cycle Moscow

OVERVIEW: Bicycling through Moscow is a fantastic way to see the beauty and vibrancy of the city in a single day or night. However, keep in mind that many roads are not bicycle friendly, and riders will find themselves crossing multiple lanes of traffic, jumping on and off sidewalks, and carrying bikes on staircases.

ROUTE: We pedaled to Moscow’s sites in approximately the following order:

Andreyevsky Bridge

Russian Academy of Sciences

Luzhniki Stadium

Novodevichy Convent

Bogdan Khmelnitskiy Pedestrian Bridge

Square of Europe

Borodnsky Bridge

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Arbat Street and Turandot Fountain

Gogolevsky Boulevard and Sholohov Monument

Cathedral of Christ the Savior and Patriarshy Bridge

Luzhkov Bridge

Bolotnaya Square and The Sins Monument

Bolshoy Kamenny Bridge

Alexander Gardens

Red Square (GUM, the Kremlin, and St. Basil’s Cathedral)

Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building

Novospassky Bridge

Club Discovery Restaurant

Red October and the Peter the Great Statue

Muzeon Park of Arts (Fallen Monument Park)

House on the Embankment

Gorky Park

How to Take a Rooftop Tour and Celebrate the Fake New Year in St. Petersburg, Russia

ROOFTOP TOURS: Sneaking onto a St. Petersburg rooftop is a great way to see the city, and the easiest way to do so is with an experienced tour guide. Fly to Myasokombinat airport in St. Petersburg, Russia or take the 4-hour, high-speed Sapsan train from Moscow to St. Petersburg. When you arrive, contact charming, English-speaking Vsevolod “Seva” Mitrofanov by phone at +7 921-893-92-17 or by sending him a message on his VK page (in Russian). Seva charges €15 per person for a simple rooftop tour, €30 for a professional rooftop photo shoot, and €75 for a romantic, rooftop picnic dinner for two.

PURGA: Purga (the Russian word for “blizzard”) is a special dance club in St. Petersburg that celebrates a Russian wedding and New Year’s Eve every night of the year. The club can be found at Fontaka River 11 (Ð½Ð°Ð±ÐµÑ€ÐµÐ¶Ð½Ð°Ñ Ð ÐµÐºÐ¸ Фонтанки, д. 11), close to the Gostinnyy Dvor Metro station.

How to Visit a Russian Banya

OVERVIEW: Fly to one of Moscow’s three international airports. From any of the airports, take the AeroExpress train and transfer to the Moscow Metro. From there, it’s easy and inexpensive to travel to most locations in Moscow.

BANYA: If possible, make Russian friends who have access to a banya at a dacha to have the most authentic experience. In lieu of that, try visiting Moscow’s oldest and most luxurious bathhouse, Sanduny Baths (14 Neglinnaya, near the Chekhovskaya Metro station), or the newer, more modern Banya on Presnya (7 Stolyarny, near the Ulitsa 1905 Goda Metro station).

Wonderful blog. I like the photographs most. The Mount Whitney photographs are of a perfect place — no words!

Would love to live in a city were every night is a New Year's Eve! Nice article.

Great read! I've wanted to go to SP for years now! I'm going!

I'm glad you love the trip )))

aww amazing! so glad you glad share this experience! as painful as it may have been im sure it was worth it for a proper "Russian experience"

That is a most evocative piece of writing, Hank. You have an artist's eye for the cultural light and shade of your surroundings and an accepting objectivity in the midst of encounters that should feel familiar but intensely don't, like tasting salt when you expected sugar. Your translation game and the photo of a wild animal's reflection in a shiny metal hub cap are perfect metaphors for what you've shared with us — not only a glimpse of that enigmatic Russian soul but also a good bit of your own.

not bad Hank, not bad at all… and this is coming from a Russian Soul ..

wonderful writing.

РуÑ??Ñ??каÑ?? душа … yeah , women are shared with modernity now ( clothes , etc ) and a deep memory of education … good done , its good to read u 🙂

As someone born in Russia and who spent all her summers at her family's dacha, this story made me laugh out loud. You captured the Russian propensity for absurdly painful experiences and the laughs that come with it quite well. Glad you enjoyed!