OCTOBER 20, 2014 — I’m struck by how exceptionally quiet it is. If I were blindfolded, I wouldn’t even know that there are thousands of people blocking the wide road in front of me. I’m walking toward Occupy Central, a huge encampment of citizens demanding true democracy in Hong Kong by peacefully protesting in the middle of Harcourt Road, a major arterial that passes by the government’s headquarters.

The basic backstory isn’t complicated. On August 31, 2014, the Beijing government announced that it would only allow Hong Kong citizens to vote for Beijing-hand-picked candidates in the election for Hong Kong Chief Executive in 2017, effectively making their upcoming election a sham. So, on September 26, 17-year-old college student Joshua Wong, along with hundreds of other student protesters, staged a peaceful protest by breaching a security wall and entering a courtyard in front of the office of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive (a courtyard that was originally a public space). The demonstrators were arrested, jailed, and released, but, on September 28, they began protesting again by blocking major arterial Harcourt Road adjacent to Hong Kong’s government complex. Thousands of other pro-democracy protesters joined them. On September 29, when the Hong Kong police attempted to remove the protesters (at Beijing’s order) and used pepper spray and tear gas against unarmed students, they only managed to anger and invigorate protesters. Quickly, the number of demonstrators increased to tens of thousands.

A sign on the Lennon Wall Hong Kong explains the protesters’ mission.

“It’s different than you imagined,” says Winky, a young Hong Kong woman I’ve just met who is walking with me through the encampment. “Much more peaceful.”

She has no idea how right she is. During my visit to Egypt during the Arab Spring revolution in Egypt in 2011, I saw people yelling and chanting loudly and angrily, protesters throwing rocks at police, and military officers with tanks. Here, I see a “Study Corner,” where students read their pre-med study materials. I see a young man sketching a protester dressed like a superhero. I see groups of friends socializing in front of their tents. I see a young woman using oil paints to paint a picture of a beautiful yellow umbrella, which has become the protest’s de facto logo after protesters used their umbrellas to defend themselves against the police’s pepper spray.

Occupy Hong Kong organizers Joshua Wong, Lester Shum, Chu Yiu-Ming, and Chan Kin-Man speak in front of a crowd.

The students are friendly, smiling at me and willing to answer all of my questions with a healthy amount of passion, which is especially laudable considering the number of journalists and tourists who have been treating them like animals in a zoo with endless photos and interviews. Of course, the students’ willingness to be photographed and the area’s seemingly endless supply of democracy-related street art is also a clear strategy. This protest is decidedly Facebook and Instagram friendly, and it’s nearly impossible for anyone walking through the encampment to resist posting a photo of the compelling paintings, wry posters, or beautiful sculptures to social media sites. The fact that the Occupy Central demonstration is so media-ready is at least as organic as it is conscious. Most of the demonstrators are Millennials who came-of-age in the 2000s, in a world where their primary modes of communication were electronic messages and social media. The media-savviness of the protesters is more a part of their souls than it is a manufactured, disingenuous social media campaign like one an American marketing company might orchestrate.

Police face off with umbrella-wielding protesters in the Mong Kok neighborhood of Hong Kong.

During my second night with the protesters, a Hong Kong woman named Charmaine introduces me to her friends Benson, Penny, and Cora. They’re no longer students, but they’re all young people passionate about democracy, and they’re thrilled to guide me through the subtleties of the politics and help me meet more protesters.

Hong Kong police don helmets and get ready to charge protesters in an attempt to clear the streets.

“We believe in democracy,” Benson tells me in forceful, fluent English. “That’s, I think, something that’s a very basic human right.” He, Penny, and Cora walk with me past the Chief Executive’s office building and the offices of the Hong Kong legislators with the fenced-off courtyard. There are tens of tents and demonstrators camped out directly in front of the building’s entrance doors. “This is where it all started,” Benson explains. “Joshua Wong scaled that security fence and was arrested.”

We walk past the building, where we see Hong Kong Police guarding Tin Mei Road, preventing demonstrators from shutting down yet another major road through the city. Tens of students are in a face-off with the police.

“Nothing will happen tonight,” Penny explains to me. “There’s not enough students here to take that road. But we like to keep pressure on the police, so it’s clear to the government that we’re serious and haven’t given up.” I hear some of the demonstrators heckling and yelling at the police. The evening before my arrival, the police were caught on video beating up a protester only 100 feet away from where I’m standing, and the incident aired on the local Hong Kong news (which, unlike mainland Chinese media, enjoys press freedom). Yesterday, Winky told me that she cried when she read about the beating. Later, I meet a young, female college student named Maggie, who tells me, “When I was small, I thought the police would bring justice, but, now, they are not.” She tells me this with such vulnerability that I feel my heart break a little as she says it.

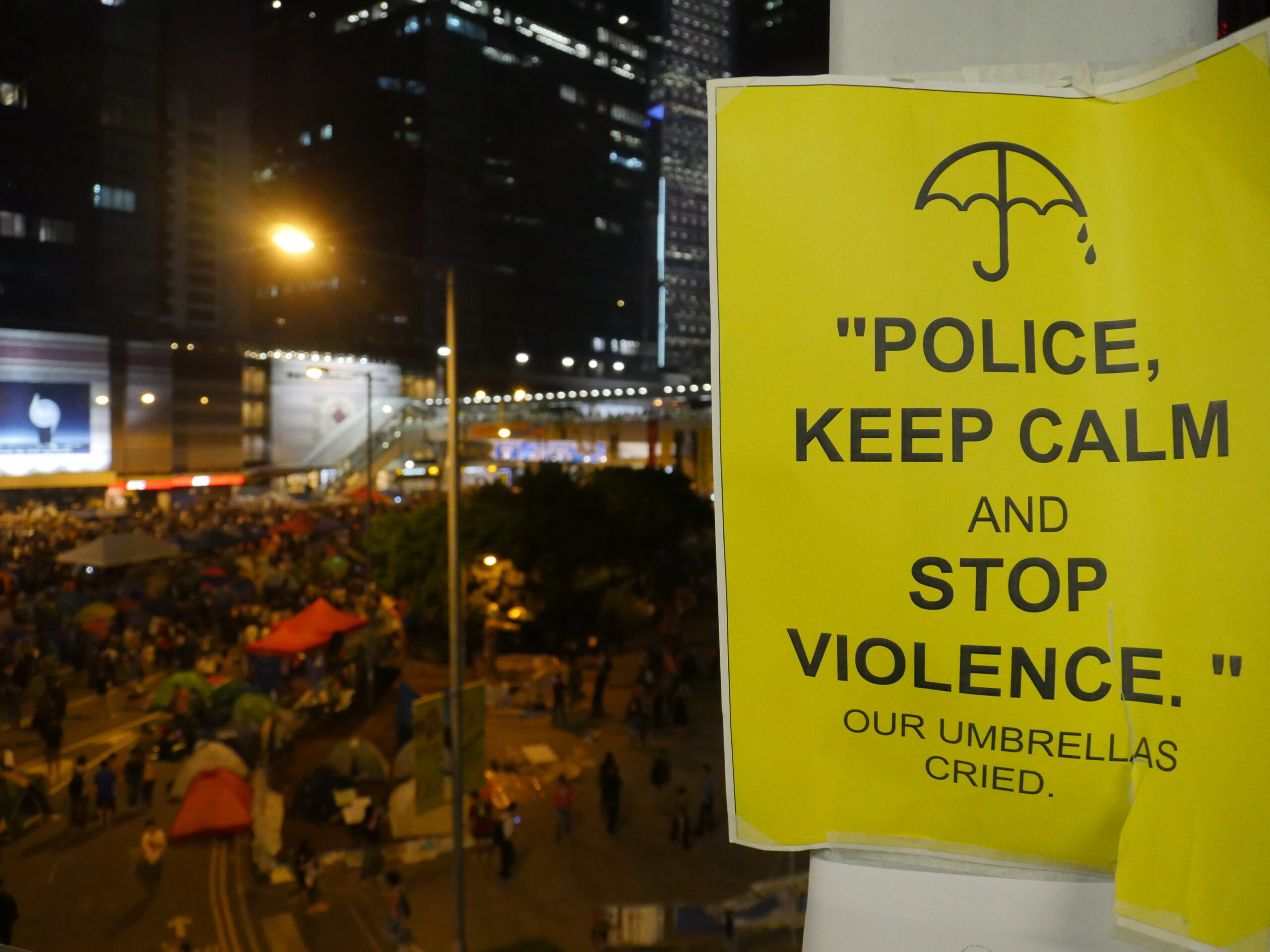

A sign pleads with the Hong Kong police at Occupy Central.

The next day, I meet Punia, a smart law student who takes me to eat a mouth-watering dim sum dinner near the protest site. She tells me that she plans on having a career in international law, and I ask her if she hopes to use her law degree to further the cause of democracy in Hong Kong.

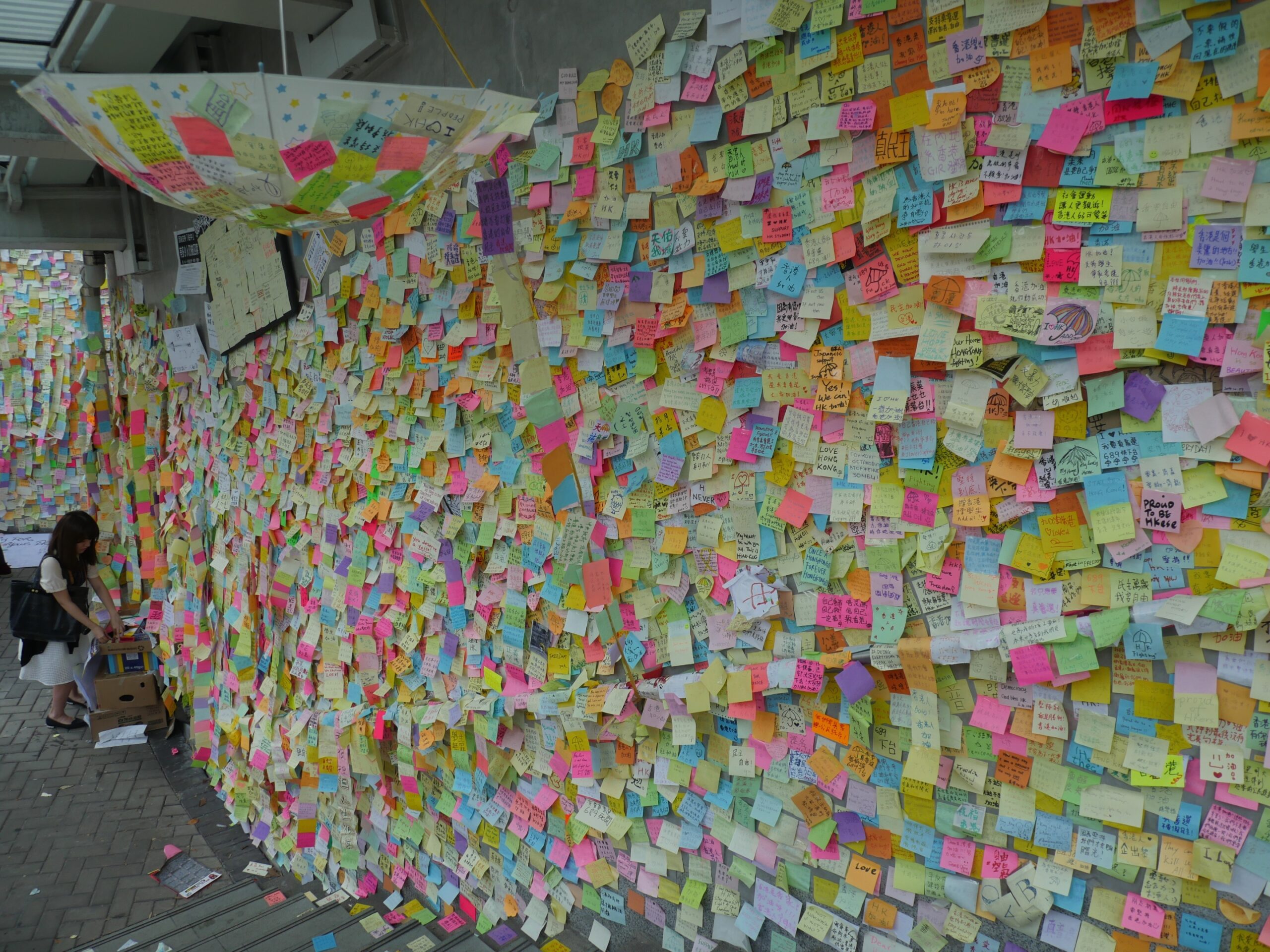

“I think I will want to take up some responsibility in this area, but I’m not sure if I have the confidence or capability to be at the forefront,” she says, sheepishly. “But, I will definitely want to be at the back, supporting, in a way.” Punia introduces me to Annabelle, another law student who loves the street art at Occupy Central and the idea of reclaiming public space. Her enthusiasm about the art is so infectious that I spend a large part of the afternoon reading thousands of messages posted on the Lennon Wall Hong Kong, a huge wall filled with colorful Post-It Notes inscribed with optimistic messages about democracy in Hong Kong.

Occupy Hong Kong’s student artists have created some beautiful street art.

In the evening, Benson texts me: “Seems like the action is at Mong Kok tonight.” There are a number of Occupy encampments throughout the city, and Mong Kok and Nathan Road is the site of the second biggest (the biggest is at the government complex). I meet him at Nathan Road near Mong Kok, and, based on how aggressively the Hong Kong police are behaving, it seems clear that they have received clear orders from Beijing to get rid of the Occupy camps. Though the mainland Chinese media is state controlled, and the Chinese government has tried to stop most news about the protests from reaching the mainland, information slips through via word-of-mouth and the Internet. One of the many risks for Beijing’s single-party government is that if Taiwan, Tibet, or other parts of China see that the movement in Hong Kong is strong, they will demand democracy too.

A woman adds a supportive message to the Lennon Wall Hong Kong.

As Benson and I walk down the road, we watch as the police systematically attempt to remove the protesters by charging toward them with helmets and shields, block by block, as they line the sides of the street behind them to prevent people from re-entering the road. I watch as the police charge forward, over and over, defending themselves with pepper spray, as demonstrators attempt to defend themselves only with umbrellas. I see one police officer hitting a protester with a baton, and other protesters being pushed to the ground, arrested, and dragged down the street. For the most part, I stay on the median with a group of journalists, filming everything I see with them. There’s a moment where I find myself in the middle of the street with a line of helmeted-police coming toward me, but, they go right by me, focusing on the protesters. In the melee, I lose Benson.

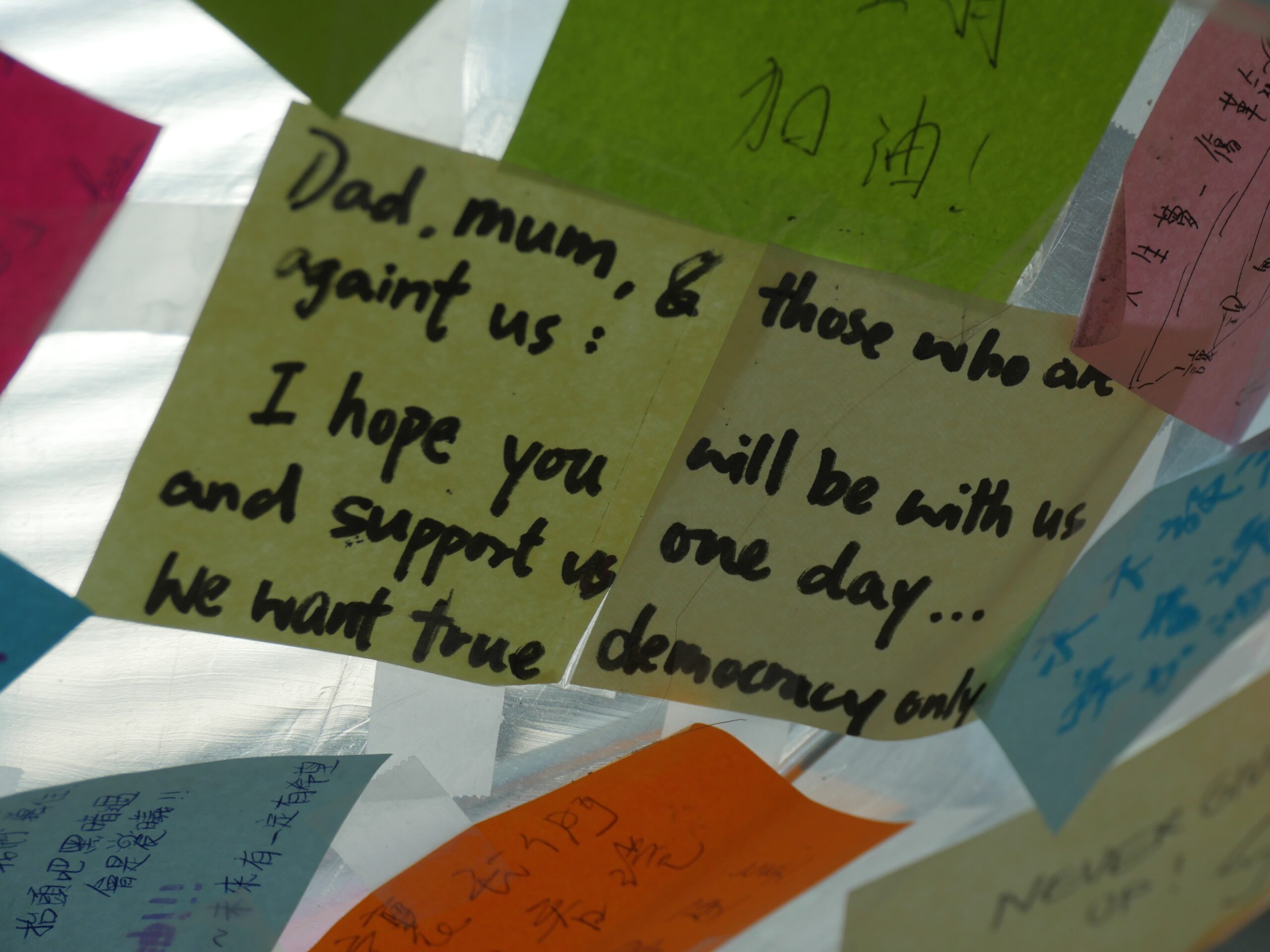

A message on the Lennon Wall Hong Kong pleads with the writer’s parents for support.

After watching the chaos for over an hour, it becomes clear to me that the police’s battle is futile. To accomplish what they want — to completely clear protesters from a road going on for miles — they would need thousands of barricades to keep people from entering the roadway from the sidewalks and tens of thousands of police to guard those barricades. It’s hard to understand why they are bothering with their fruitless mission, because it’s only making the demonstrators angrier and reinforces the students’ point of view: that Beijing is too oppressive and out of touch with real life in Hong Kong.

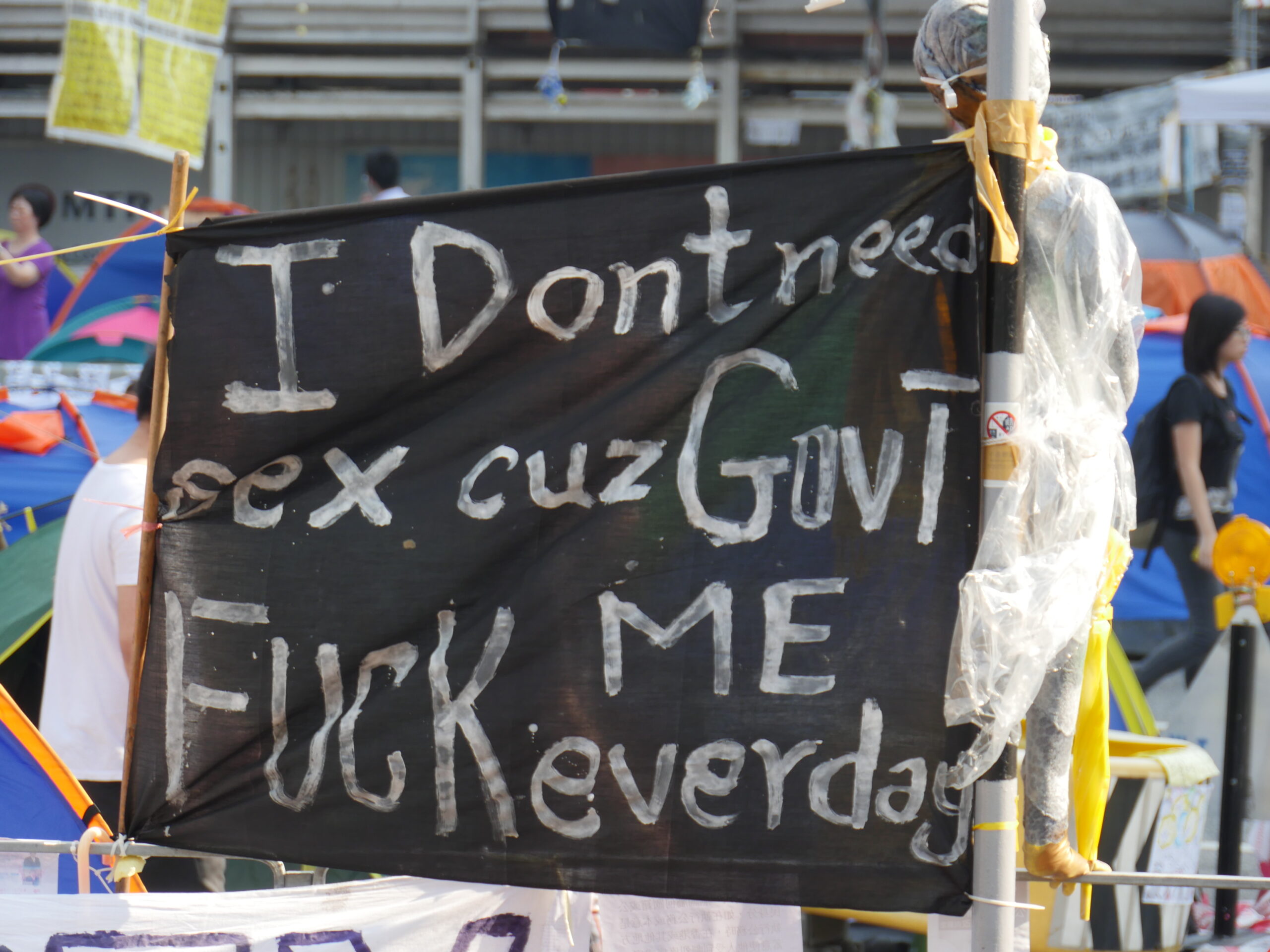

A sign complains about the government at Occupy Central.

As the police slowly move farther down Nathan Road, demonstrators begin filling in behind them, surrounding the police. Quickly, the police commanders realize they’re out numbered, and, finally, after hours of charging at the students, they retreat into police buses. Immediately, protesters swarm the streets and rebuild their own barricades so they can reinstate their street encampment. They cheer and clap, and Benson’s friend Cora tells me, “It shows that Hong Kong people will fight for democracy ’til our death.”

After spending four days and nights with Occupy demonstrators, during my last night in Hong Kong, I meet a young accountant named Rice, who reveals to me that she is against the Occupy democracy movement. “The students are getting very emotional,” she tells me. “It’s so sad that they’ve been brainwashed.” Rice tells me that she attended one of the most pro-democracy universities in Hong Kong, but never bought into the rhetoric. “Things are good in Hong Kong already,” she explains. “The pro-democracy politicians just want to get power for themselves.” Rice isn’t the only person in Hong Kong who feels this way. A poll conducted by Chinese University reports that 46 percent of Hongkongers do not support the Occupy Central protests, and Rice tells me that she thinks that there may be many more who are afraid to say so publicly. She tells me that she is afraid to discuss the issue with her coworkers, because she know that most of them support the democracy movement.

Protesters camp in the entrance to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council Offices.

“China is not ready for democracy,” Rice tells me. “Who knows what could happen if the government gives the protesters what they want?” As an American, I support democracy and believe that citizens of the world should be able to choose their own leaders. Nevertheless, I’m aware that when Egypt’s revolution ousted brutal dictator Hosni Mubarak, the country democratically elected Mohammed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, only to have him forcibly removed by the Egyptian military. Even with Egypt’s recent election of yet another new president, it remains to be seen whether democracy will work there yet.

Similarly, no one knows what’s next for Hong Kong. Of course, I hope that the complex, fascinating city becomes a smoothly functioning, true democracy. But, democracy or not, I can only hope that whatever the future holds, it’s good for the people of Hong Kong.

This is a masterpiece. I am a pretty cold fish but it is bringing tears to my eyes. These are China's best children.

A far more intelligent, constant and committed people, so young and so alone, hated by business, more scorned by power, than those of us who staged people power in the Philippines. Vindication lies not in victory it seems but in courage whatever the result. What a generation.

The idea of limiting the democratic choices of children of this quality to a bunch of filthy rich Hong Kong businessmen in the pockets of their friends boggles the mind. Beijing should know better. Chinese communism started with young people like these.