FEBRUARY 17, 2012 — “Let’s meet at the water wheel,” I say into my cell phone, aware that I sound like I’m reading from a script for a bad romantic comedy. I’m setting up a date with a 25-year-old Chinese girl named Christine or Yin — depending on whether you’re an English or a Chinese speaker — who I met a few days before while she was working as a receptionist at a hotel in LìjiÄng, China. On the way out of my inn, I glance at the entrance sign, which reads: “Mid-Leuelf Haliday Viewing Hatel.” This is going to be a hilarious rom com, I think, as I head toward LìjiÄng’s most famous and romantic landmark.

The rooftops of LìjiÄ??ng, China, seen from a hotel room window.

The 12-foot-tall wooden water wheel at the entrance to LìjiÄng Old Town (an UNESCO World Heritage Site, quickly being destroyed by careless development), illuminated by spotlights, glows golden yellow in the darkness, as I search a sea of hundreds of Chinese tourists for Christine. Though she is attractive, I admit that I’ve asked Christine to have dinner partly because her fluent English gives me a chance to get some of my burning questions about China answered by someone with whom I can communicate. As an added bonus in terms of learning about China, she is a member of the Bai ethnic minority, one of 55 recognized minority groups apart from the country’s Han Chinese majority.

Woman perform taichi in LìjiÄ??ng, China.

“Where should we eat?” I ask after finding her, standing five feet tall with black hair and a checkered wool coat, hidden in front of the water wheel. “You know the LìjiÄng restaurants better than I do.”

“Have you had Across-the-Bridge Noodle yet?” she asks. I tell her that I have no idea what she’s talking about. I’m already starting to suspect that I may have judged her English too kindly.

“Follow me,” she says. As she leads me through the maze of narrow alleys of LìjiÄng’s Old Town, she starts telling me a story about a faithful Bai wife who once had to take soup across a bridge to an island where her husband was studying for his imperial exams (the tests used to determine those fit for the government bureaucracy in Imperial China).

“She loved her husband very much, so she was frustrated when the soup always became cold on the long walk to visit him,” she explains. “So, one day, she decided to separate the ingredients and bring him a boiling hot broth covered with a layer of oil. It stayed hot for the entire trip, and her husband loved the hot broth because it let him cook the soup’s ingredients as he ate.”

Clothes hang in shops in LìjiÄ??ng, China.

Sure enough, soon after we sit down at the restaurant, the waitress brings us a boiling hot broth with a variety of raw vegetables, seafood, and meat. Christine and I start cooking our food together, but I keep losing vegetables and meat in the broth due to my incompetence with chopsticks. I’m embarrassed, but Christine laughs and her eyes twinkle. Playing the role of the tale’s dutiful Bai wife, she starts feeding me the hot food with her chopsticks. I feel ridiculous, but our meal ends up seeming a little like the Italian restaurant spaghetti scene from Lady and the Tramp — transported to a bizarre, Chinese-noodle rom com universe.

Mountains tower behind the streets of DàlÇ??, China.

While we eat, Christine tells me that she grew up in a very rural nearby county, working on her parents’ farm. When she performed well on China’s high-pressure, college-entrance exams, she ended up being one of the few people in her county and the only in her family to go to college, where she perfected her English. After teaching for a couple years in a poor, rural farming town, she decided to move to Chinese-tourist haven LìjiÄng, a city of 1.2 million people, to make more money. There, she got a coveted job as a receptionist at an expensive international luxury hotel due to her excellent English.

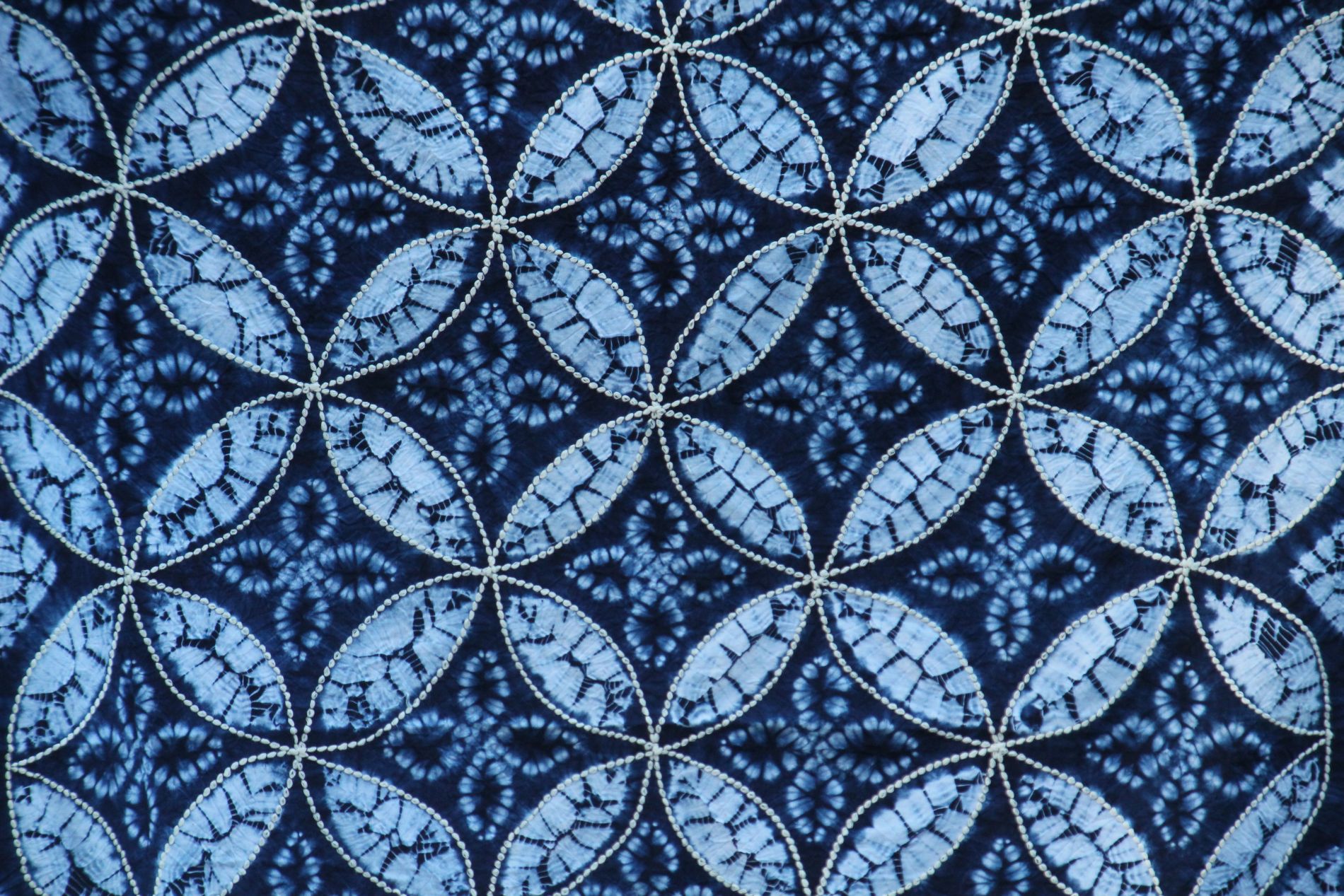

Bai wax-dyed cloth hangs from a clothesline in a market in DÃ lÇ??, China.

“Do you like the job?” I ask.

“Sometimes, but I don’t really understand it,” she says. “How can people spend US $1,500 on one night in a hotel villa? It doesn’t seem fair to the poor kids in my school who didn’t even have clothes.” When I ask her about her salary, she tells me that she earns US $2,000 per year and lives in a hotel dorm with four other employees.

“I can’t imagine spending that much on a hotel room either,” I respond. (Though I met her at her hotel, I was there only to have dinner at its restaurant before returning to my US $20/night hostel). “Some people are very rich, though.” She looks visibly distraught.

“My manager, who I work harder than, makes US $16,000 a year!” she complains. “It doesn’t make sense!” I feel like she’s expecting me, an American, to justify capitalism and her hotel’s employee pay structure — or even fix it — but I have no idea what to say.

“Well, it’s clear that China has changed a lot in the past ten years,” I say vaguely. “Do you think the country’s move toward a free market is a mistake? Are you worried about the future?”

“I have a great hope for China,” she says. “Things are much better. But, I’m very worried about economic inequality.”

Bai wax-dyed cloth hangs from a clothesline in a market in DàlÇ??, China.

“Yes, it’s a problem everywhere in the world,” I say, thinking of the woman in Tiger Leaping Gorge who latched onto me for US $3 and wouldn’t let go. When I mention Tiger Leaping Gorge to Christine, she tells me that she’s never visited it — despite the fact that it’s only a two-hour bus ride away.

“You’ve seen more of China than I have,” she says. “I’ve never left Yúnnán Province.”

“If you could go one place, anywhere in the world, where would you go?” I ask her.

“The Sagrada Família,” she says, referring to the well-known, unfinished Catholic church in Barcelona, Spain. “A Catholic missionary once gave me a bible, which at first read I thought was just a fairy tale. But, then I came to believe that God is all powerful, and I became a Christian. I saw the church once on TV, and ever since I’ve wanted to visit it.”

Street musicians play guitars in DàlÇ??, China.

For a fleeting moment, I have an urge to buy the US $1,400 roundtrip ticket to Barcelona for her right then and there on my iPhone. It would be cheaper than staying one night in her hotel, after all. But, I can’t imagine that she’d approve of using that much money for a plane ticket either.

And, then, despite my vehement protests, she insists on paying for our Across-the-Bridge Noodles.

When we return to the water wheel and say goodbye, I get the feeling that I’ve just met the sweetest girl in all of China. I want to tell her to visit me sometime in Los Angeles, but I don’t. Instead, I silently wish that, if she ever gets a chance to take a trip out of the country, she goes directly to Barcelona.

A man sells sugar-covered strawberries in DàlÇ??, China.

I spend the last day of my three-week China trip in nearby DàlÇ, wandering in the shadow of Cangshan Mountain, through markets filled with vivid navy and white Bai wax-dyed cloth, the textile for which the town is famous. At dusk, I’m surprised to hear U2’s “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For” drifting from a street corner. I go to investigate, and I meet two street musicians: an American named Scott and an Irishman named Nick. They tell me that they met while traveling in China years ago, started a band, and, like so many other backpackers who I’ve met during my trip, never left.

A woman sells fruit in DàlÇ??, China.

“Chinese pop music is so horrible,” Scott explains, “that we felt like we had to start a rock band. We make enough money playing gigs and on the street to get by.” Nick suggests that I stop by Bad Monkey, DàlÇ’s oldest expat bar, where they often play live music.

So, after dinner, I walk into Bad Monkey by myself. Scott and Nick see me and nod, as they strum away, playing American rock classics, a welcome change from the sappy ballads I became accustomed to in Yángshuò. I look around the bar, which is full mostly with Chinese tourists, but, a pretty, dark-haired, blue-eyed Western girl sitting with two other Western guys catches my eye. When I ask the girl if I can join her table, she introduces herself as Tessa, and says that she’s a Dutch medical student. She also introduces me to her two friends, whom she just met: Kevin, a student from Utrecht, Netherlands, and Tom, a carpenter from the UK.

A help-wanted sign hands in DàlÇ??, China.

“I think we should start a band,” I tell them, as we drink a table full of Tsingtao Beer. “It’s my last night in China, and I’m not ready to leave. See those guys on stage? They started a band and never left. I think we could do it too.”

“I’m in,” Tessa says as she takes a swig of beer. “Let’s name the band Drunken Horses.” And, just like in any good romantic comedy, I fall in love with her immediately.

The night turns into exactly the kind of night you want to have on the last night of a long trip. The beer keeps flowing (much of it bought for us by a drunk Chinese tourist) as we plunge into a manic planning session for the Drunken Horses’ first album. We decide that Kevin will play drums, Tom will play harmonica, Tessa will be the lead vocalist, and I’ll play guitar. We agree that the album’s first song will be titled, “Mr. Ed,” in keeping with our horses theme, and it will be a homage to the famous television steed. After Tessa tells us the sad story of a breakup with an ex-boyfriend, we write the lyrics for a second tune titled, “When You Break Up With Your Boyfriend and He Gets Rich.” After a multicultural car crash centered around our trying to order French fries, we write a third track titled, “French Fries, Chips, Crisps, and Ketchup.”

An unhelpful “schematic diagram” hangs in a bus station near DàlÇ??, China.

As the night winds down after we’ve hammered out most of the details of our band’s album, Mr. Big’s “To Be With You” starts playing on the bar’s stereo. Tessa and I, sitting side by side, look at each other. We start harmonizing together, singing the song as a duet.

I’m the one who wants to be with you, Deep inside I hope you’ll feel it too. Waited on a line of greens and blues, Just to be the next to be with you.

Even with the abysmal acoustics at this obscure dive bar in rural China, we sound good. I realize that we’d make a pretty great band.

Hey. What a surprise: I found your website! At first, I searched "Casbah Cafe, LA" and it led me to your site. Then, I clicked into the home page, and I found that you were traveling in Yunnan. I was there 1 month ago. I loved it there. We did the same route. I haven't had the time to go through all your articles yet, but I am so interested in getting to know you. I am looking forward to hearing from you. BTW, I am Chinese!

Your story is interesting! These kinda stories seem happen in Yunnan a lot. I met a bunch of friends in Yunnan and we were the best travel team ever.

Jun: Thanks for the kind words! I'm glad you like the site, and it's always great to hear from someone reading my site from overseas! Yes, Yunnan was my favorite place out of everywhere I went in China. Dali especially was a lot of fun. Keep traveling!