NOVEMBER 28, 2014 — After making a short film about protesters demanding democracy in Hong Kong, I decide to spend three weeks trekking through Nepal. I lose about 15 pounds during the grueling, 111-mile, Mount Everest-area trek, so when it’s over, I’m really, really hungry. I decide to return to Hong Kong — to eat.

Soon after I arrive, my Hong Kong friends Benson and Cora invite me to an Oktoberfest event at Happy Valley Racecourse, a popular horse racetrack on Hong Kong Island. At the track, I see locals and tourists of all ages and ethnicities, packing the stands. (Hong Kong is much less homogeneous than the rest of China due to its history as a former British territory.) After squeezing my way through the crowd to the track’s beer garden, I find the two drinking beer and eating sausage and sauerkraut. It’s not exactly the Chinese-food smorgasbord that I dreamed about while in Nepal, but my over-cranked metabolism doesn’t care. I start in on a scrumptious sausage.

Kam Wah, a traditional Hong Kong cafe, serves an excellent traditional pineapple bun with butter.

“How’s Hong Kong doing?” I ask them, wondering about the ongoing Occupy Hong Kong protests. Benson tells me that not much has changed; both the protesters in the streets and the Chinese government in Beijing remain unmoved. Cora, a strong supporter of the movement, says that she has been camping out in the streets frequently in Mong Kok (one of the rowdiest protest sites), but her mom doesn’t approve of her involvement.

“My parents swam to Hong Kong from mainland China — or that’s what they say, anyway — to escape the Communists,” Cora says.

“But, wait, they’re against Occupy?” I ask. I had assumed that Hong Kong immigrants from China who fled from China’s oppressive government would support the democracy protests, regardless of their age.

“My parents, and most Hong Kong parents, are afraid of Beijing,” she explains. “They don’t want us to do anything to ruin how good things already are in Hong Kong.” It takes me awhile to internalize this. It’s a painfully practical idea: when people fear an authoritarian, power-obsessed single-party government, it’s safer for them to do everything they can to avoid angering or challenging the government, knowing that leaders are likely to tighten their control over any citizens who threaten their power. But, it’s also a sickening idea: oppressed people end up encouraging authoritarian governments’ human-rights abuses, because the risk of trying to change the governments’ behavior is too high.

Fluffy scrambled eggs and toast are the Australia Dairy Company’s signature dish.

In the 1980s and 1990s, many Hongkongers were very afraid. After the British agreed, in 1984, to hand over Hong Kong to China, nearly one million Hongkongers fled the country, mostly to the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Presumably, the emigrants were afraid of what would happen to Hong Kong when the Chinese government took control in 1997, especially after the government killed nearly 1,000 demonstrators during the Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing in 1989. But, many stayed in Hong Kong. It was their home, after all.

As we talk, the horses race around the track. We all decide to bet on the second-to-last race, and I place a HK $50 (US $7) bet on a horse named You Read My Mind.

“If anyone wins big, let’s all agree that we’ll buy a yacht, live on it, and leave Hong Kong to sail around the world,” I say. “Benson will bring his girlfriend, Cora will bring her boyfriend, and I’ll commission everyone to find me a girlfriend before we set off on our trip.”

“I love this idea,” Cora says. The way she says it makes me wonder how much she and Benson are afraid of what the Chinese government will do with Hong Kong in the future.

The three of us cheer wildly as the horses and jockeys sprint around the track. We watch as You Read My Mind finishes in third place, good enough for my bet. I win 190 Hong Kong dollars (US $25), but it isn’t quite enough to buy a yacht.

Bean curd dessert with brown sugar can be found at most Hong Kong cafes.

“I guess we’re staying in Hong Kong,” Benson says, disappointed.

The next day, with my metabolism still dying to eat all food in sight, I decide to go on a Hong Kong culinary tour and visit some classic Hong Kong cafes. My first stop is Kam Wah, a classic cha chaan teng or traditional Hong Kong café. I order one of Hong Kong’s best known foods, a pineapple bun (polo baos in Cantonese): a moist, slightly sweet mass of bread, stuffed with a huge pat of butter and topped with melted sugar (supposedly giving it a pineapple’s texture). When I taste it, it’s so deliciously rich and sweet that I can almost imagine confusing it with a doughnut, if it weren’t for the salty butter inside, perfectly balancing the bun’s sweetness. I also devour one of the café’s Hong Kong-style egg tarts, which is flaky, smooth, and sweet, though it makes me miss the perfect, mouth-watering egg tarts made at bakeries in Portugal.

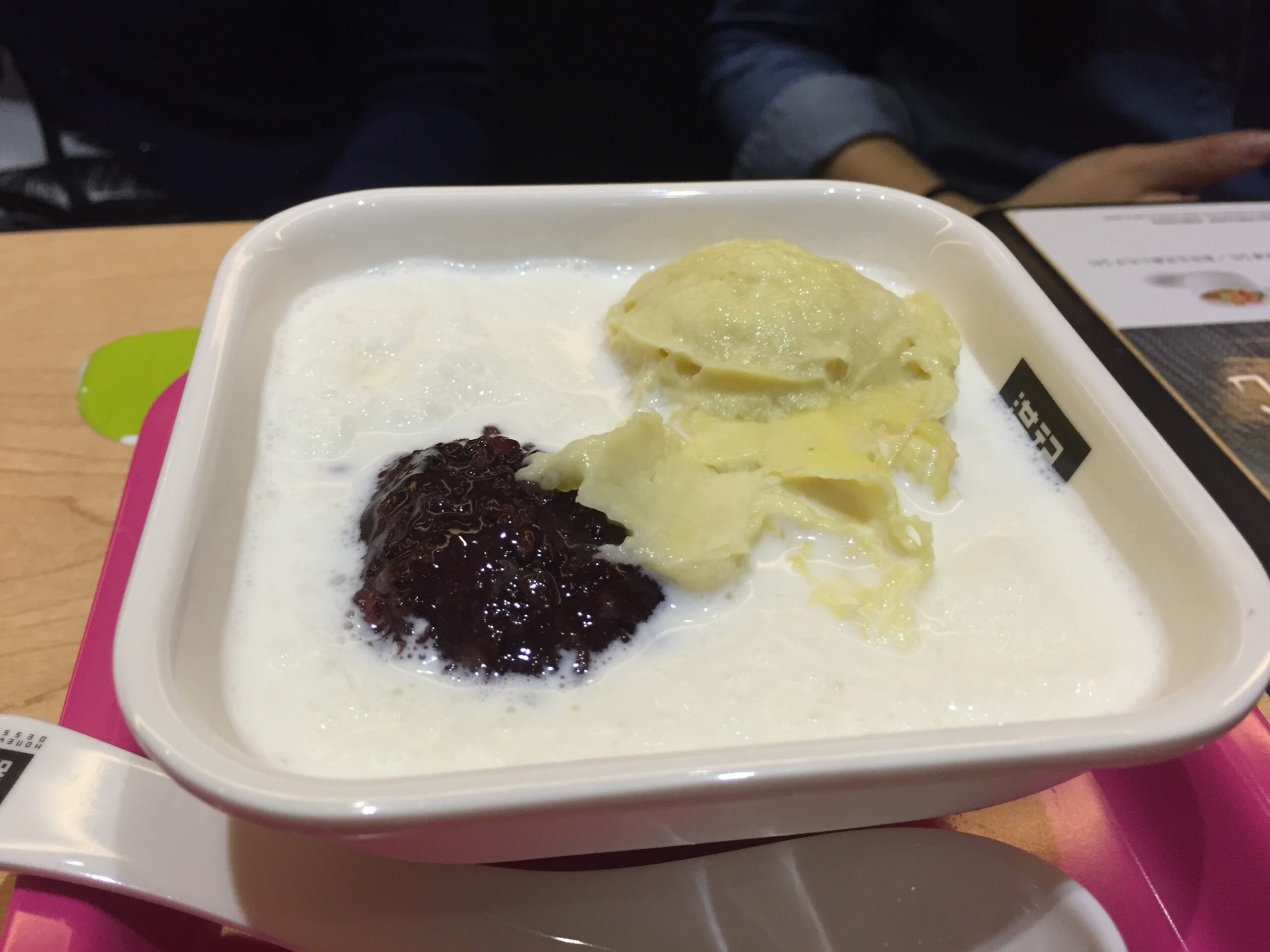

Honeymoon Dessert serves durian with black glutinous rice in milk.

Next, I head to the Australia Dairy Company. Though its name sounds like it was created by a marketing firm for a corporate chain of ice cream shops, it’s actually a Hong Kong classic, opened in the 1960s. My favorite thing about classic Hong Kong cafes is that they’re so cramped inside that, to maximize space, the staff seats customers at tables with strangers. When I arrive at Australia Dairy Company, the host immediate seats me at a table with an old Hong Kong couple and a middle-aged Hong Kong woman, and they all give me a shy once-over.

I order the café’s classic breakfast dish: scrambled eggs and toast, which the brusque but speedy waiter brings within a minute. I take a bite of the eggs. They’re heavenly. I never knew scrambled eggs could be so fluffy, so moist, and so buttery. I suspect there may be a secret ingredient (lots of butter or lots of cream), but, regardless, these HK $20 (US $2.50) are so worth the money that I try to order a second helping. The Cantonese-speaking waiter doesn’t understand what I want (though it’s hard to believe that wanting more of these eggs is a rare occurrence), but the woman at my table comes to my rescue and helps. After my meal, she waits for me outside the restaurant, introduces herself as Candy, and proceeds to demand that I start being even more adventurous with Hong Kong food, making a long list of foods she thinks I must try. Before letting me go, she even buys me some piquant fish balls from an adjacent street vendor to start me on my quest. They’re quite good.

Traditional Hong Kong pantyhose milk tea is served at Lan Fong Yuen.

Now, certain that I need an expert foodie to push me into the next level of Hong Kong food nirvana, I ask Fiona, a Hong Kong teacher and self-professed foodie, to take me on a food tour of Mong Kok, one of Hong Kong’s most food-dense neighborhoods. We start by attacking a hodgepodge of street food, including delicious fish dumplings, aromatic fish tofu, and a lovely bean curd dessert with brown sugar. Quickly, though, I find out that these items are only warmups for Fiona’s grand afternoon food plan: classic, sugary Hong Kong pantyhose milk tea (named for the shape of the filter used), tasty, savory pork sandwiches, and creamy kaya French toast at Lan Fong Yuen. Incredibly, she follows all of this with a pungent dessert of durian and black glutinous rice in milk at Honeymoon Dessert. I start to suspect that we’ll never stop eating.

“When I used to play rugby, I used to eat lots of food after games because I was so hungry,” Fiona tells me. “Then, after I got hurt and stopped playing rugby, I just kept eating.”

My crowning achievement, however, is when she demands that I try pig intestines on a stick smothered in a burning, spicy sauce at street vendor Fei Jie. I’m terrified that I won’t be able to stomach the mass of red and orange pig entrails on a stick, but in the end, I discover that the fiery sauce blanketing them mostly hides the fact that I’m eating rubbery pig innards. Fiona laughs at me when I take a bite, but when she eats hers, even she looks nervous.

Pig intestines are served on a stick at the Fei Jie restaurant in Hong Kong.

“This is [only] my second time I take this,” she admits, swallowing reluctantly.

In the evening, Fiona and I join another of her teacher friends, Justine, and we decide to relax at the upscale RED Bar in IFC Mall, Hong Kong’s tallest building, which has overpriced drinks but magnificent views of Victoria Harbour and the Central skyline.

“Aw, I wish I could go out for drinks like this more often,” Fiona says. “None of our coworkers will ever get drinks after work because Hong Kong teachers are so conservative.”

“Not even one drink?” I ask.

“No teachers want to get caught drinking,” she explains. “And we never talk about Occupy [the democracy protests] at work. It’s too risky. Teachers are expected to be unbiased and respectable.”

The next night, my food tour continues when my friend Winky — who originally guided me through the Occupy protests — and I grab a beer at Grand Pub in the Prince Edward neighborhood, where I decide to order a dish of shaved beef with a Chinese sauce from the bar. To my surprise (American bar food is usually abysmal), the meat is tender and flavorful, and the scorching red sauce compliments the meat perfectly. As we eat the Chinese meal, we discuss Hong Kong’s generational political divide. Winky tells me that her grandparents emigrated to Hong Kong from China, but, like so many other grandparents and parents, they don’t approve of Winky being involved in the protests.

The Cheong Fat dai pai dong is one of the few remaining outdoor restaurants in Hong Kong.

“My parents don’t want us to anger the government,” Winky says. “But, China is not a good steward of Hong Kong. I have no faith in the future of this place under China. The British should have built in punishments into the agreement, in case China didn’t do what it said it would do.”

A few days later, I convince Jessica, a Hong Kong chef, to take me on yet another food run, this time in the Sham Shui Po neighborhood. First, we hit up a popular Hong Kong seafood restaurant called Man Fat, where we eat a bone-marrow seafood dish and a classic meat and potatoes dish. Then, we head to Se Wong (Snake King), where Jessica strongly suggests that I try the restaurant’s signature dish: the snake soup. Once I get past the psychological gross-out factor and try it, it’s almost impossible for me to differentiate the taste from salty chicken noodle soup, though I still feel a bit uncomfortable watching live snakes slithering around a cage next to our table. While we eat, Jessica points to some large jars above us.

The homemade fish balls at the Cheong Fat dai pai dong (outdoor restaurant) are unmatched in Hong Kong.

“The Chinese believe that snakes can be very healthy,” she tells me. “You can buy snake skin or snake guts here too and eat them if you are sick.”

“I think this is probably enough snake for now,” I say, slurping up another bite of snake soup.

My last stop with Jessica is my favorite, because we visit a traditional dai pai dong, a type of outdoor restaurant that used to fill streets throughout Hong Kong years ago. I feel like I’m following in the footsteps of Martin Booth, who secretly eats at these restaurants without his parents’ knowledge in Golden Boy, his fascinating book about growing up in Hong Kong. I also remember that the Mrs. Chan character in the beautifully understated Hong Kong movie In the Mood for Love is obsessed with eating the noodles at a pai dong. At the Cheong Fat dai pai dong, Jessica and I watch a man make noodles from scratch and a woman stir a pork hock stew, right on the street. It’s pretty amazing.

Man Fat restaurant serves a bone marrow seafood dish.

When we sit down, the aged woman who serves us demands that we order everything she has on the menu: noodles, fish balls made from scratch, and a pile of pork hock. Jessica laughs as the woman hovers over me to make sure I’m eating everything the “right way,” telling me to add more sauce to my noodles and fish balls and eat all the meat on the pork hock. I find the gooey texture of the pork hock unpalatable, but the succulent noodles and yummy fish balls are sumptuous! It occurs to me that some of my favorite Hong Kong foods — scrambled eggs on toast, grilled beef, and homemade noodles — are noticeably uncomplicated. Sometimes, simple is best.

In the morning before I leave for the airport, I head to Wong Tai Sin Temple, a Taoist shrine known for answering prayers and telling fortunes through kau cim, or Chinese fortune sticks. There, I meet a woman named Ally, a Hong Kong college student who has been praying at the temple since she was a child and who strongly supports the Occupy Hong Kong democracy movement. As we walk through the temple, she tells me that she’s traveled through China, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and India by herself.

“I’m impressed,” I say. “You must have cool parents.”

“My parents are not typical Chinese,” she explains. “They even kind of support the [Occupy Hong Kong democracy protests], because they think it’s good for students to try to make some changes,” Ally tells me. “Other parents think we shouldn’t bother, because they think trying to change the government is useless, and we’re affecting everyone in Hong Kong.” I’m fascinated, because this is the first time I’ve heard of any protester’s parents supporting the democracy movement.

New Italian restaurant Gradini in the Pottinger Hotel serves grilled octopus. (photo courtesy of Gradini)

When Ally leaves to go to a meeting, I stay at the temple and decide to visit one of the temple’s fortune tellers by following a process Ally explained to me: I borrow two canisters of Chinese fortune sticks, shake them until a number falls out of each, and then bring the numbers to a fortune teller sitting nearby.

“Numbers mean stories,” the fortune teller tells me. “Ask me any question, and I tell you an answer.” For my fortune stick labeled “60,” I ask the fortune teller when I will get married. She tells me that she doesn’t know, but that 2014 is a bad year for me to get married. This isn’t news to me. I decide to ask a less self-focused question.

“Okay, for the number 10,” I ask, “what will happen with the Occupy democracy protests? Will Hong Kong get a democracy?” She stays quiet for a long time.

“Story number 10 is about a lazy son,” she finally tells me, cryptically. “He must work very hard for what he wants. He must work very, very hard.”

During the week after I left Hong Kong, the Chinese government renewed their interest in ending the Occupy Hong Kong protests and ordered police to remove all protesters and encampments from the Hong Kong streets by force. In the process, the police arrested protest leaders Lester Shum and 18-year-old Joshua Wong. The police succeeded in clearing some protest sites, but demonstrators continue. They have vowed not to give up and, every day, they continue fighting for democracy in Hong Kong.

The Best Food in Hong Kong

PINEAPPLE BUN at KAM WAH: This classic Hong Kong cafe serves traditional Hong Kong pineapple buns right out of the oven (if asked), and the only thing better than their perfect texture and rich flavor is the huge pat of butter hiding inside. 47 Bute St; Metro: Prince Edward or Mong Kok.

SCRAMBLED EGGS at AUSTRALIA DAIRY COMPANY: I didn’t know that scrambled eggs could be so fluffy, moist, and buttery before I ate these. At HK $20 (US $2.50), they’re one of the best breakfast values in Hong Kong. 47 Parkes St; Metro: Jordan.

EGG TARTS at HONOLULU COFFEE or HOOVER CAKE SHOP: If you like egg tarts, you’ll be happy to discover they can be found in almost every Hong Kong bakery and café. I thought the one I ate at Kam Wah was fine, but I’ve read that the ones at Hoover Cake Shop and Honolulu Coffee Shop are especially good.

PEARL MILK TEA at GONG CHA or COMEBUY: Bubble tea may be a Taiwanese creation, but it can be found all over Hong Kong. I have always loved bubble tea, but the “Gong Cha Milk Pearl Milk Tea” (a bad menu translation that gives a customer milk tea with tapioca pearls topped with milk foam) at Gong Cha brought my bubble tea love to stratospheric levels. The Gong Cha menu is quite complicated, so be sure to do some exploring. I also like the milk tea at Comebuy and love their 3Q Passion Tea. I have no idea what the 3Q means or what’s in the tea, but it tastes good. Gong Cha and Comebuy can be found all over Hong Kong and in cities around the world, including New York.

EGG WAFFLES (GAI DAAN JAI) at ANY STREET VENDOR: These waffles, shaped like egg cartons, can be found at street vendors all over Hong Kong. Their “bubbles” makes them easy to eat with their hands, and the sweet, buttery tasty of the dough means you’ll want to grab one for every walk to work or home.

PIG INTESTINES at FEI JIE: Though you can get fried pig intestines at nearly any Hong Kong street vendor, locals stand in long lines to buy the peculiar, cold pig intestines served on a stick at Fei Jie. I didn’t get a second helping because of the rubbery texture, but I did think that the spicy sauce smothered over them tasted pretty good. 55 4A Dundas Street; Metro: Yau Ma Tei.

SNAKE SOUP at SNAKE KING (SE WONG YEE/FUN/SUN): Once I got past the psychological gross-out factor, it was difficult to differentiate this from the taste of chicken noodle soup. Plus, the Chinese swear by the health benefits of eating any part of a snake. Hong Kong locals are faithful to the soup at Snake King, which has branches all over the city. 30 Cochrane Street; Metro: Central, 24 Percival Street; Metro: Causeway Bay, or Fortune Mansion; Metro: Wan Chai.

NOODLES and FISH BALLS at CHEONG FAT DAI PAI DONG: Visiting a dai pai dong, or outdoor food stall, in Hong Kong is a must-do experience (while some still remain) because they give a taste of Hong Kong’s food culture 50 years ago. The noodles made from scratch and homemade fish balls at this pai dong are worlds better than those you’ll find at any other street vendor. 1 Yiu Tung Street; Metro: Sham Shui Po.

KAYA FRENCH TOAST at LAN FONG YUEN: Hongkongers cut their French toast into nine, bite-sized pieces, and you should too. The kaya toast at Lan Fong Yuen is creamier and eggier than most in the U.S. 2 Gage Street; Metro: Central, or 304D, 3/F, Shun Tak Centre, 168-200 Connaugh Road Central; Metro: Sheung Wan.

MARGARITA PIZZA at MOTORINO: The margarita pizza at upscale Motorino in Central was the best I ate in Hong Kong, which isn’t saying much considering the sad state of Hong Kong pizza. 14 Shelley St.; Metro: Central. Locals say that the Paisano’s chain is good, but for anyone who has eaten pizza in New York or Los Angeles, Paisano’s soggy, under-baked slices disappoint (though their huge slices are a great value).

BRUNCH at THE MARKET at HOTEL ICON: This brunch buffet not only has exceptional variety and quality — the eggs benedict, dim sum, tandoori chicken, pizza, and apple crumble were all great, and it’s not easy for a chef to get so many different types of food right at a buffet — but its price (HK $490/US $63), while expensive, is a decent value for the food quality at this high-end hotel. 17 Science Museum Road; Metro: Hung Hom or Tsim Sha Tsui. Though I like The W Hong Kong as a hotel, compare the Icon’s brunch to The W’s, which not only costs a ridiculous HK $858/US $110, but the food is hit-or-miss.

GRADINI at POTTINGER HOTEL: The 20-foot high ceilings, marble tables, plush seating, and muted colors of this new Italian restaurant in the boutique, Pottinger Hotel in Central makes diners feel like they’ve fallen into the surprisingly comfortable living room of an Italian king. Highlights of my meal included the burata, the grilled octopus, and the lobster. 74 Queen’s Road Central; Metro: Central.

SAUSAGE EGG MCMUFFIN at MCDONALD’S: I think it would be a mistake not to mention this essential tip: 24-hour McDonald’s are all over Hong Kong, and, unlike American McDonald’s, they serve the venerable Sausage McMuffin with Egg, all day and all night. (Warning: The muffin itself is significantly softer than those in the US to align more with the food preferences of Hongkongers.)